Stretching from north to south and surrounded by the sea, Japan's culinary culture has developed based on the four seasons and is centered on savoring the seasonal blessings of the foods of the fields, mountains, and sea.

From ancient times, the Japanese have valued seasonality as an important part of daily life and have referred to various calendars as a way to enrich their lives. Calendars, such as nijushisekki (24 solar terms) which indicate different stages of the seasons such as risshun (start of spring), geshi (summer solstice), and shunbun (autumnal equinox), and shichijuniko (72 pentads) that express more subtle seasonal shifts is deeply related to the Japanese food culture, used as a guide to follow the seasons and to practice agriculture.

In "Teishoku of the Seasons," we'll be sharing the appeal of enjoying seasonality through the seasonal foods used in teishoku, an everyday meal for the Japanese, as well as introducing the relationship between the ancient calendars (handed down to present day) and the food culture.

In 2018's installments of "Teishoku of the Seasons," in addition to the seasonal menus covered so far, we'll also be looking at dishes for events from across Japan—with a focus on Kyoto, the city that birthed Japanese culture during its 1000-year reign as the nation's capital. Our country, Japan, sees the beauty in the changing of the seasons. By enjoying the plentiful flavors that the seasons yield, we give thanks to nature for its blessings. Let's delve deeper into the Japanese food culture that has been passed down for countless generations.

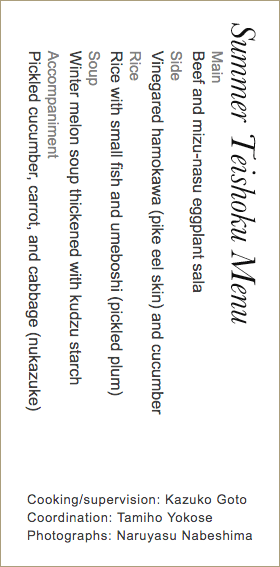

Our summer teishoku makes good use of vibrant seasonal ingredients to offer up a delicious menu that’s welcome even at a time of year when appetites fade.

Mizu-nasu eggplant can be eaten raw, and complements beef wonderfully.

Enjoy with a light Dressing that uses Japanese mustard to give it a little bite.

- Mizu-nasu eggplant

- 2

- Beef (thinly sliced)

- 200g

- Edamame (beans)

- 50g

- Perilla (approx. 10 leaves)

- One bunch

- Salt

- As required

- Pepper

- A small amount

- Vegetable oil

- As required

[Dressing]

A

- Japanese mustard (if desired*)... 1-2 teaspoons

- * Can be replaced with Western mustard.

- Vinegar... One and a half tablespoons

- Olive oil... As required

- ❶Break the mizu-nasu eggplant into six equal pieces by hand and lightly sprinkle with salt.

The eggplant pieces will produce water after a period of time, so wipe them with a paper towel. Boil the edamame in salt water and remove the beans from the pods. - ❷Sprinkle the beef with salt and pepper. Heat the vegetable oil in a frying pan, fry the beef one slice at a time, and put the fried beef to one side.

- ❸Mix the ingredients for group A except for the olive oil in a bowl. Next, gradually add the olive oil and mix it in to create the dressing.

Adjust the amount of mustard used as desired. - ❹Add the ingredients from steps ❶and❷ to the dressing from step ❸ and mix well. Prepare the salad in a bowl, then cut half the perilla leaves into squares and sprinkle over. Cut the remaining perilla leaves into thin strips and place on top as garnish.

Tips

Mizu-nasu eggplant is becoming increasingly popular, so please do try making this dish if you find some! Use less beef if you plan to make this dish as a side. This dish goes well with white wine.

Kuzu-hiki is a kind of soup thickened with kudzu starch that is often eaten in Kyoto. The addition of ginger encourages perspiration, which helps you feel a bit cooler after you eat one of these soups.

The hamo (pike eel) of Kyoto are delicious during the summer. We cooked the skin with sauce and shredded it into thin strips, mixing it with cucumber to make a vinegared dish (sunomono). Enjoy the contrast of textures of the hamokawa and cucumber.

We mixed small fish and umeboshi in with some freshly-cooked rice. The rich taste of the fish and the sourness of the umeboshi pair together to make this a wonderfully refreshing rice dish for the summer.

Every July, the Gion Festival fills the streets of Kyoto with color. The festival is one of the major festivals of the Japanese seasonal calendar, and takes place at Yasaka Shrine in eastern Kyoto. The Gion Festival has a history over a thousand years, and can be traced back to 869.

At this time, Kyoto and other areas across Japan were badly stricken by an epidemic of disease. The people performed a ritual to drive away the god of pestilence, in which they erected 66 halberds, symbolizing the 66 provinces of Japan at the time, and carried mikoshi (portable shrines) throughout the city. This is believed to be how the Gion Festival originated. Features of the festival such as the mikoshi, hayashi musicians, and the craftsmanship of the parade floats have since influenced festivals throughout Japan.

During the Yamahoko Junko parade, one of the biggest highlights of the Gion Festival, people march with floats called yamahoko that come in various shapes and sizes and are particular to individual neighborhoods of the city.

The parade takes place twice: once for the sakimatsuri on July 17, and once for the atomatsuri on July 24.

The Gion Festival is also sometimes called the Hamo Festival. People traditionally say that hamo acquires a richer flavor after it drinks the rain during Japan’s rainy season. Hamo are at their fattiest state during the time of the Gion Festival, right after the end of the rainy season, and the fish is a key feature of seasonal summer food in Kyoto. Dishes like hamo otoshi (parboiled hamo) with shredded dried plum, hamo teriyaki, and hamo sushi are classic features of Kyoto’s hamo cuisine.

orn as the eldest daughter of the grand master of Mushanokoji-senke, one of the three main schools of Japanese tea ceremony. Goto studied ceramics as an art history major at Doshisha University. Her dishes, based on kaiseki-ryori which she received training from her mother, a leading pioneer of chakaiseki-ryori (a traditional meal served to guests before a tea ceremony), incorporates different ingredients and cooking styles she encountered from her frequent visits abroad. Her dishes, arranged for the contemporary household, embody the culinary culture and soul of Japan.

—Vice President to Washoku Japan.

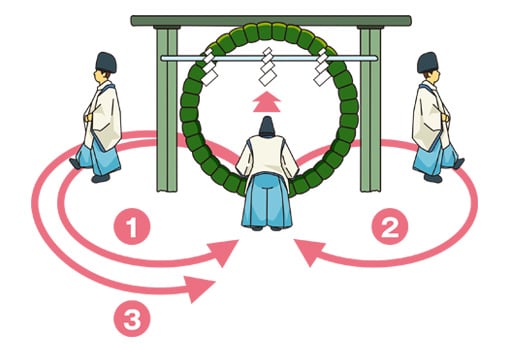

Every sixth months, on June 30 and December 31, oharae cleansing rituals take place at shrines to purge sin and impurity. At the summer purification ritual (nagoshi no harae) that takes place on June 30, people purify their minds and bodies by passing through a ring made from cogon grass. Nagoshi gohan is a recently-created dish for this event, based on traditions of the summer purification ritual.

The Rice Stable Supply Support Organization.

This rice-bowl dish takes inspiration from the story of how Somin Shorai—a kami of purification, who inspired the grass ring tradition—offered the kami Susano a bowl of millet rice. The rice for this new dish, mixed with cereals and grains, contains millet and adzuki beans (which are traditionally said to drive away malevolence), and is topped with a thick, round piece of vegetable tempura made using green and red seasonal vegetables (with the green color representing the grass ring, and the red as an auspicious color that also drives away malevolence), served with a grated ginger sauce. Ginger, too, is said to ward off disease and misfortune.

During the summer purification, a large ring made from cogon grass and straw is installed in the shrine. By passing through the ring three times in the correct manner, people cleanse their minds and bodies of impurity and pray for good health.

When passing through the grass ring, people chant the following prayer:

- Start by standing in front of the ring, then bow and step through. (First prayer)

- ① Turn left, then return to the front of the ring, bow, and step through it again. (Second prayer)

- ② This time, turn right, then return to the front of the ring, bow, and step through it once again. (Third prayer)

- ③ Finally, turn left, return to the front of the ring, bow, step through it, and proceed to the altar to worship.