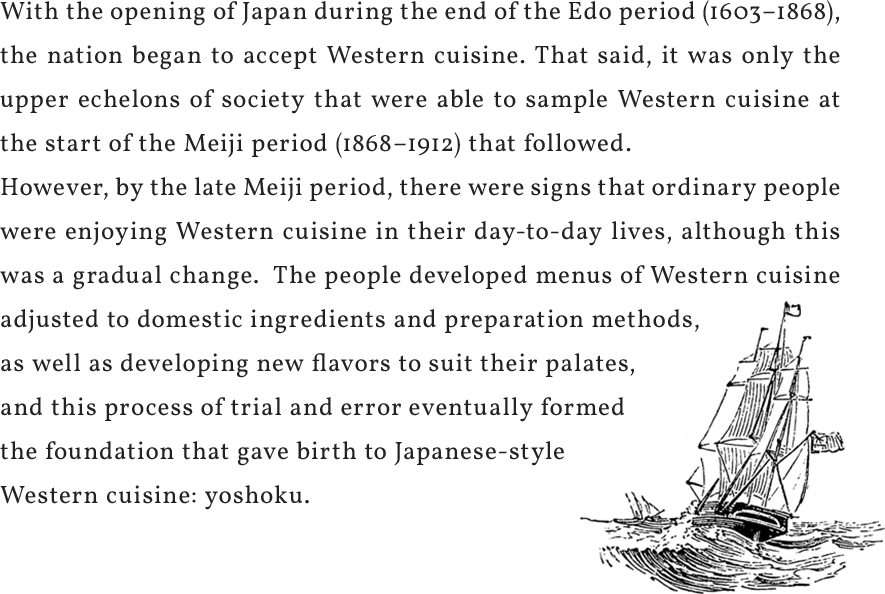

At the start of the Meiji period, the government promoted efforts to westernize eating habits, which was backed politically by national policies. First, in 1873 (6 years into the Meiji Era), French cuisine was instated as the cuisine to be used in official occasions, for reasons relating to diplomatic relations with Western countries. Additionally, as part of the effort to “enrich the country and strengthen the army” (fukoku kyohei), leaders sought out a nourishing diet to improve the physique of the people, and the taboo on eating meat, which had long been avoided in Japanese history, was lifted. In connection to this, Western-cuisine restaurants began to open across Japan, but at this point in time, they were only patronized by a select group of people, such as the political classes and the wealthy. It was a time when there was still a strong resistance to eating meat, often the main dish of Western cuisine.

(National Diet Library Collection)

that opened in Minamikayaba-cho,

Nihonbashi in 1886

(Photograph courtesy Ginza Renga-Tei)

By the middle of the Meiji period, consumption of Western cuisine began to shift from special occasions among the elite to more quotidian consumption. This was due in part to the efforts by cooks who strove to tailor Western cuisine to Japanese tastes. Perhaps one example of this is the pork cutlet by Ginza Renga-Tei, which developed the style of adding

shredded cabbage and serving with rice.

From the mid-Meiji period to the late Meiji period, people began to develop “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine” (wayo secchu ryori) to replace authentic Western cuisine, and this served as the foundation for modern yoshoku. The labors and processes of trial and error during this time led to the birth of yoshoku such as tonkatsu and omelet rice, which came

with the start of the Taisho period (1912–1926).

Incidentally, the word yoshoku also appears in materials dating from the Meiji period. However, it was mainly used as a close synonym for “Western cuisine” then, and it only during the late Meiji period that yoshoku gradually came to be recognized as meaning “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine”.

Additionally, at the end of the Meiji Period, the “ippin yoshoku” business model (“one-dish yoshoku”, a format where “yoshoku” was sold at stalls using leftovers and second-hand cutlery from yoshoku restaurants) came about, providing people from a wide range of social strata the opportunity to eat yoshoku.

one of Ginza’s most historic restaurants,

founded in 1902

(Photography courtesy Shiseido Parlour)

(National Diet Library Collection)

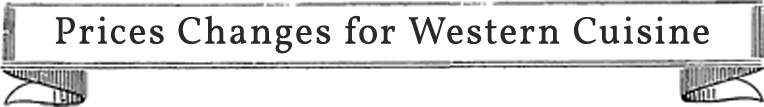

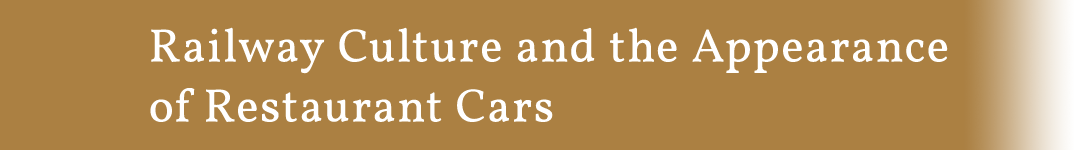

During the Meiji period, the people of Japan worked vigorously toward building a new country. Railways, which offered dramatic improvements to the efficiency of transporting people and resources, were essential infrastructure to the modernization of Japan. Western cuisine also developed alongside the rise of railway culture. Following the opening of the

Shinbashi to Yokohama railway route in 1872, restaurants and cafes started to open on station premises. Apparently, a restaurant serving Western food even opened on the premises of Shinbashi station within the same year.

Furthermore, as long-distance travel increased with the growth of the rail network, it became increasingly necessary to provide food to passengers on the trains. In 1899, the first restaurant car was introduced on Sanyo Railway’s Kyoto Station to Mitajiri Station (current-day Hofu Station) route, and it seems Western cuisine was served there. However, Western

cuisine at the time was still expensive, and it was likely limited to the wealthy upper classes using the train. Furthermore, in 1901, a restaurant car operated by the Western-cuisine restaurant Seiyoken appeared on the Tokaido Main Line (Shinbashi Station to Kobe Station) express trains. (The restaurant car sold meat dishes for 15 sen and vegetable dishes for

12 sen, with a sen being 1/100th of a yen.) Railways, the latest transport method of the time, served a role in the spread of fashionable Western cuisine.

(National Diet Library Collection)

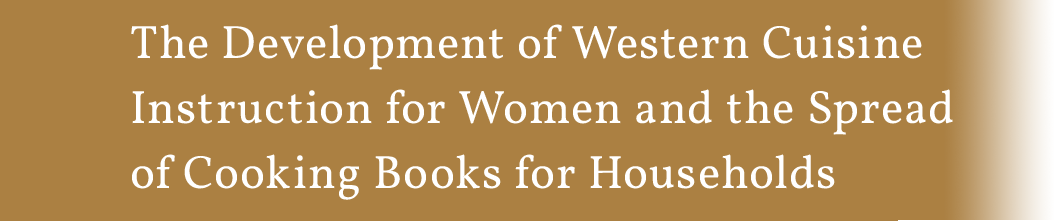

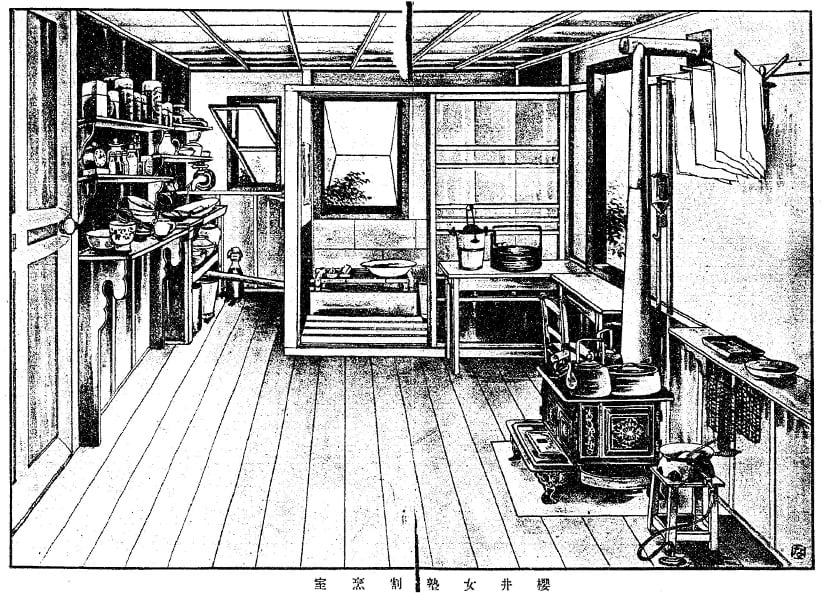

Part of the reason Western cuisine spread into ordinary households is due to the improvement of cooking education for women and the spread of cooking books for households. Until the modern era, dietary matters were not given a great deal of attention in female education. However, following the Meiji period, the habit of depending on servants for cooking

became criticized, with emphasis instead placed on the importance of the practice of cooking at home.

With this trend, there were also more opportunities for women to study Western cuisine outside of the home. In fact, even in the cooking instruction books used at girls’ high schools in the Meiji and Taisho periods, one can see that there was an aspiration toward acquiring new knowledge, with the inclusion of recipes for Western cuisine such as curry rice,

omelets, and stew, as well as depictions of cooking implements like stewpots and frying pans.

(Photograph courtesy Japan Women’s University, Naruse Memorial Hall)

Meanwhile, during the late Meiji period, the first organizations planning Western cuisine lessons targeting middle-class women were established in urban areas. These activities were another opportunity to push Western cuisine into Japanese households. For example, “Seiyo-ryori nihyakushu (200 Western Dishes)” (1904), a Western-cuisine cooking book published in

Osaka, contains records of lessons held by an organization called “Society for the Study of Yoshoku”, for which the opening ceremony was held at an independent hotel in Nakanoshima Park.

It is clearly stated that the organization was established to promote learning about nourishing Western food, rather than traditional Japanese cuisine, and one can infer that this was aimed not only at housewives, but also unmarried daughters. Furthermore, even while there was opposition to Western cuisine at the time, one can also see arguments being made that

acquisition of highly nutritious “European and American-style Western food” would nourish “husbands”, active members of society and also secure familial bonds. In other words, managing the health of families came to be emphasized in the household cooking of the Meiji period.

“Katei jitsuyo seiyo-ryori no shiori (Practical Guide to Household Western Cuisine)” (1907)

(National Diet Library Collection)

(National Diet Library Collection)

Additionally, while Western cuisine was praised for being highly nutritious, “Katei jitsuyo seiyo-ryori no shiori (Practical Guide to Household Western Cuisine)” (1907) and other works attempted to combat misunderstandings, like the idea that “Western food means one or two meat dishes”, and devise recipes that could be cooked with easily procured

ingredients, without necessarily adhering to a meat-eating diet.

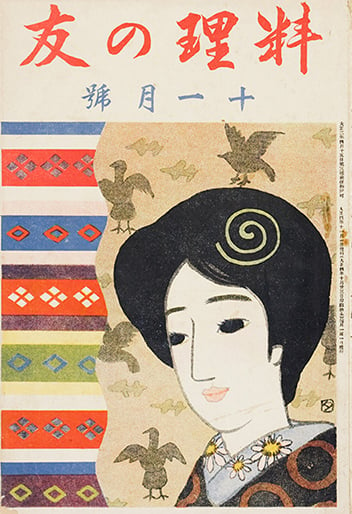

Furthermore, during the late Meiji period to the Taisho period, more and more Western cooking books were published featuring recipes that could be made using the utensils and seasonings people had available at home. From the 1900s, experienced female writers were constantly producing Western cooking books for households, and there were many recipes created

with Japanese preferences and lifestyles in mind.

Western cooking in household cooking magazines

https://www.syokubunka.or.jp/library/ryourino-tomo/191511

(Ajinomoto Foundation For Dietary Culture Collection)

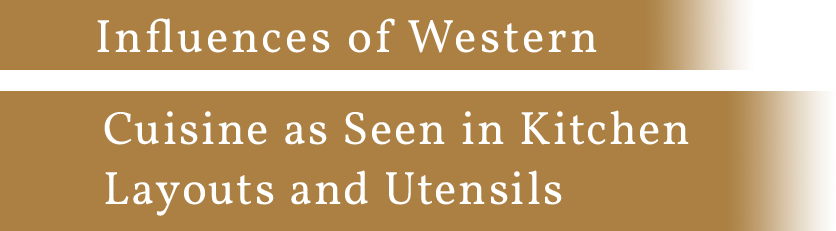

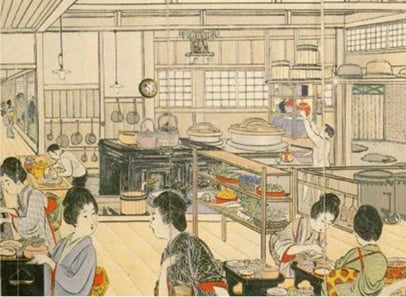

During the Edo period, the kitchens of common people were divided into a space on the floor focused around a kamado (wood-fueled stove), and a dirt floor space focused around the nagashi (wash basin or sink). People would kneel while cooking in these kitchens (tsukubai-shiki daidokoro), and this style persisted for some time even after the start of the Meiji period.

Center/Cooking while kneeling (National Diet Library Collection)

Right/The kitchen of the Shigenobu Okuma residence

However, from the mid-Meiji period, infrastructure like electricity, plumbing, and gas started to make headway into urban, upper-class households, and from this period, Japanese kitchens also started on the road to modernization based on those of the West. For example, a major bestseller of the Meiji Period, “Kuidoraku (The Pleasure of Eating)” (1903), describes the kitchen of the Shigenobu Okuma residence, fitted with modern equipment. The most attractive details of this kitchen, perhaps, were the British-made gas stove and the large gas kamado for cooking rice in the center. (Incidentally, it was during the Taisho period that gas pipes truly began to take hold as part of the infrastructure.)

(National Diet Library Collection)

Coming into the Taisho period, depictions of women standing while cooking began to appear even in household cooking books. Standing kitchens like these were praised for their hygiene and functional benefits, and they were touted as the ideal, rational kitchen during the movement to improve lifestyles that was in full sway at the time.

(National Diet Library Collection)

Japan Archives

One can see signs of Western cuisine appearing on the dining tables of urban households in a variety of materials from the late Meiji period to the Taisho period. For example, the cooking book “Shiki no daidokoro (Four Seasons of the Kitchen)” published in 1910 includes records of meals for an entire year at a privileged Tokyo household. Here, one can see that they were served well-known Western cuisine such as omelets, sandwiches, chicken cutlets, and “rice curry” (an earlier term for what became curry rice). In these Western meals, while there were days with full Western courses, there were also a number of other serving styles, such as serving Western cuisine with rice and Japanese soups, or serving Western cuisine as a side dish. One can see how even in upper-class diets, Western cuisine could still be partially assimilated into the meals that these people were accustomed to.

Written in Kyoto at the same time as “Shiki no daidokoro”, the diary of a middle-class woman states that full-course Western meals were only served twice a year. There are also records of her occasionally enjoying making stuffed cabbage using Chinese cabbage, and omelets using leftovers from the previous day.

She also went to Western food classes, a favorite activity of middle-class women, where she was given the opportunity to learn how to make stew and ice cream, and also learn about other things like buffets.

Records like these show that in urban lifestyles, Western cuisine and ingredients were starting to make inroads, bit by bit.

In the late Meiji period, “Japanese-Western fusion cuisine” that differed from authentic Western cuisine began to appear, and it was from the Taisho period that Western food adapted to Japanese styles started to be called yoshoku, establishing its place as popular fare. Let us take a look at the recipes for rice curry and croquettes that can be found in the cooking books of the time.

(Photograph courtesy Rose Hotel Yokohama)

Curry is often associated with Indian cuisine, but the first curry that was introduced to Japan is best viewed as Western food that came to Japan via the United Kingdom, which governed India at the time. One can trace the early beginnings of curry recipes in Japan as far back as “Seiyo o-ryori o-kondate (Menu of Western Dishes)” (1867), written just before the Meiji Restoration. This document was submitted to the foreign affairs office of the shogunate by Kyubei Mikawaya, who opened a Western-cuisine restaurant in Tokyo during the Meiji period. One can see two kinds of curry described here, using both English and Japanese vocabulary: shrimp curry (“curry [in Japanese: white rice with sauce], ‘lobster’, rice [in Japanese: a kind of shrimp, white rice, turmeric, made with palm oil, foreign seasoning]”) and chicken curry (“curry [in Japanese: white rice with sauce], chicken, rice [in Japanese: young hen, white rice, turmeric-based sauce]”).

During the Meiji period, curry recipes using a large number of ingredients appeared the Western-cuisine cooking book “Seiyo-ryori shinan (Western Cooking Instruction)” (1872). To make these, one started by chopping leek, ginger, and garlic, then frying these in butter, and after simmering with ingredients like beef, chicken, shrimp, oysters, sea bream, or

Japanese brown frog, adding curry powder and flour before simmering further. There is also “Kappo sowa dai-ni-kan: yoshoku kappo (Cooking Collection Vol. 2: Western Cooking)” (1907), a cooking book from the late Meiji period, which contains a recipe for beef curry that describes putting black pepper on rice, placing it in the middle of a plate, and pouring

the curry on top. Meanwhile, “Yoshoku to kashi no koshiraekata (How to Prepare Western Food and Confectionary)”, published the following year (1908), suggests that when serving, the rice and curry can be left separate, but that they are best eaten mixed. Additionally, “Yoshoku no chori (Preparing Western Food)” (1911) contains a “beef rice curry” recipe

featuring a curry made with carrots, onion, and potatoes. You can also see how the ingredients popularly used today are all included here.。

One of the interesting things about Meiji-period curry recipes is that they frequently used milk. Perhaps this was an attempt to moderate the spiciness of the curry?

(Photograph courtesy Shiseido Parlour)

Croquettes are a popular food even today. Recipes for croquettes appear in cooking books from the late 1880s to the late 1890s. The croquette recipe included in “Jicchi oyo keiben seiyo-ryori-ho shinan - Mei-seiyo-ryori hayamanabi (Practical, Convenient Western Cooking Instruction - Quick Guide to Famous Western Cuisine)”, published in 1888, includes a

version similar to mince cutlets, in which hamburger meat was formed into balls or flat discs, coated with flour, egg, and breadcrumbs, then deep-fried. There is also another version in which cooked meat is chopped, mixed with a mashed mixture of onion and boiled potato, and then fried in the same manner as described above. However, the croquette recipes

seen in Meiji-period cooking books also include those where the croquettes were fried without covering them in breadcrumbs, as well as those which did not include potatoes and were similar to mince cutlets, presenting signs that a process of trial and error was taking place. With that said, the croquettes of the Meiji period certainly were eye-catching,

somewhat luxurious items you would find in a Western-cuisine restaurant. They were not something that commoners would casually eat.

However, with the arrival of the Taisho period, opportunities to make Western food at home continued to increase, and the recipes for croquettes made with potatoes became the standard. Originally, potatoes were introduced into Japan in the 16th century, but for a long period of time, they had been seen as feed for horses. Following the First Sino-Japanese

War, the Russo-Japanese War, and the First World War, the public’s perception of potatoes changed when they served as a substitute for rice, and potatoes gradually began to take their place on the dining table. The popularization of croquettes was spurred on further by the hit song “Kurokke no Uta (Croquette Song)” by Taro Kaja Masuda (1917), and this firmly

cemented their place as a true Japanese soul food.

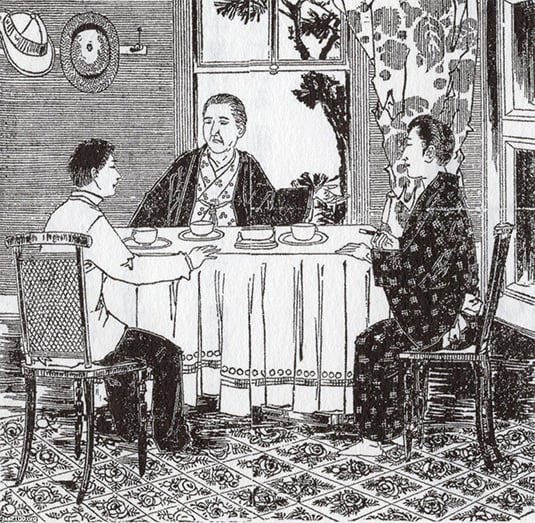

With the start of the modern age, as Western culture was spreading, writers who discussed their encounters with yoshoku began to emerge. For example, “Tokyo no sanjunen (30 Years in Tokyo)”, published in 1917, describes Katai Tayama’s reminiscences of Meiji-period rice curry.

![“Stay a while before you go. What’s the harm?” Kunikida stopped me, pulling at my sleeve almost hard enough to take it off.“We’re going to make rice curry, so come and eat with us,” said Kunikida, leaving for the kitchen. [...]I shall never forget what it was like—freshly-cooked rice heaped onto a large plate, then haphazardly mixed with a kind of curry powder mixture, the result of which I devoured with a spoon.

“Delicious, truly delicious,” we said as we ate. (Katai Tayama, “Tokyo sanjunen”)](../img/roots/spread/text-12-pc.png)

Incidentally, the encounter between Katai and Doppo Kunikida occurred in 1896, the 29th year of the Meiji period. One cannot help but imagine the charming scene of these kindred spirits eating rice curry made by Doppo’s wife in this depiction of their first encounter.

Additionally, Natsume Soseki, who was born during the Meiji period, was also a big fan of yoshoku. In Kyoshi Takahama’s essay “Soseki-shi to Watashi (Soseki and I)” (1918), there is an unusual anecdote that takes place in Matsuyama, with which Soseki is associated.

This anecdote is understood to be from 1897, and one can see Soseki being quite the gourmand in a way that seems rather unlike the dyspepsia associated with him. Additionally, Kyoshi’s anecdote also gives us a hint of how Western dietary culture was gradually spreading to regional areas.