From the period that rice-growing was brought to Japan approximately 3,000 years ago, right up to the present day, our ancestors toiled to find a way to grow a large amount of rice on narrow terrain.

Japan is described in the Kojiki, a record of the country’s development into a nation, as the “Country of Lush Reed Plains,” a reference to the bountiful growth of rice and an indication of how rice has symbolized Japan since ancient times.

In this corner, we will introduce you to Toyama’s diverse rice culture through its history, culture, and beautiful natural scenery.

Mt. AkagiThe Jomo Karuta card game refers to Mt. Akagi with the phrase “susono wa nagashi Akagiyama” (“Mt. Akagi, skirted by long plains”). Akagi Shrine is often considered to be a spiritual hot spot.

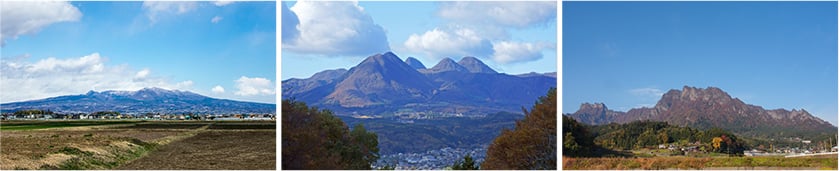

Gunma Prefecture is an inland prefecture located almost in the center of Honshu, the main island of Japan, and because of its shape, it is called "the crane-shaped Gunma Prefecture" by the Jomo Karuta, a local card game based on the culture of Gunma. During the feudal era, it was known as Kozuke Province, also known as Joshu. Spanning from the Mikuni Mountains, which run from Gunma’s west to its northern border, to Nikko in the northeastern part, there is a 2,000-meter-high mountain range. Three mountains in the central part of the prefecture, Mt. Akagi, Mt. Haruna, and Mt. Myogi are known as the Three Mountains of Jomo (Jomo Sanzan—“Jomo” being an old word for Gunma). The Kanto Plain starts toward the southeast. There is an elevation difference of over 1,000 meters between the towns of Kusatsu in the northwest, famous for its hot spring resort, and Itakura in the east end, and there are large differences in climate the between different regions of Gunma. In northwestern Gunma, it snows a lot in winter, and the annual precipitation exceeds 1,700 mm, while in the southern plains, the annual precipitation is about 1,200 mm. In winter, dry wind blows over the mountains in the northwest—a phenomenon popularly known as “karakkaze”.

The Tone River boasts the largest basin area in Japan and is also known by its nickname, Bando Taro. It originates from Mt. Ominakami in the northern part of Gunma, and brings water from many other rivers as it traverses through the central part of the prefecture. However, Gunma’s water supply in general has been lacking since ancient times, and the land is unsuitable for rice production. This is due to the quick-draining volcanic ash soil resulting from the repeated eruptions of a number of volcanoes, such as Mt. Akagi, Mt. Haruna, and Mt. Asama on the border of Nagano Prefecture.

Gunma’s ancient predecessor was Kamikenu Province, which flourished as a central province of Yamato rule, with many ancient tombs and ruins remaining to this day. In ancient times, it was a key traffic point connecting the Tosando and Tokaido highways, as well as the Hokurikudo highway provinces through station roads and other government roads. In medieval times, it was a strategic point where the Todo highway, connecting the capital and Oshu (the old province of northeastern Honshu), and the Kamakurado highway, connecting Kamakura and Shin-Etsu (modern-day Nagano and Niigata), intersected. In the Edo period (1603–1867), the various roads centered on the Nakasendo highway were a hotbed of traffic and commerce, and even today, Gunma is an important binding point for expressways and the Shinkansen.

Gunma is also famous for its many clear streams flowing into the Oze and Tone rivers, its thriving natural environment, and hot springs such as those of Kusatsu, Ikaho, Minakami, and Shima. Though Gunma’s rice production has historically been lacking, the prefecture remains a substantial agricultural and livestock center known for its Joshu Wagyu beef, Shimonita green onions, shiitake mushrooms, and a strong flour-based food culture, represented by okkirikomi. It is also an area with developed industries, such as the automobile industry and traditional handicrafts.

Middle:Mt. Haruna (Takasaki, Higashiagatsuma, and Shibukawa)

Right:Mt. Myogi *1 (Annaka, Shimonita, Tomioka)

These three mountains, the Jomo Sanzan (Three Mountains of Jomo), have been the object of mountain worship since ancient times. Close to the major city of Edo, they were popular destinations for pleasure jaunts, and even today, people of the prefecture fondly regard them as the mountains of their hometowns. Above:Mt. Akagi (Maebashi, Shibukawa, Showa-mura, Numata, Midori, and Kiryu)

Middle:Mt. Haruna (Takasaki, Higashiagatsuma, and Shibukawa)

Below:Mt. Myogi *1 (Annaka, Shimonita, Tomioka)

These three mountains, the Jomo Sanzan (Three Mountains of Jomo), have been the object of mountain worship since ancient times. Close to the major city of Edo, they were popular destinations for pleasure jaunts, and even today, people of the prefecture fondly regard them as the mountains of their hometowns.

Right:Haniwa figure of a standing armored man. Image courtesy of Tokyo National Museum / Image: TNM Image archives

Earthenware figures were made in the Jomon period (c. 14,000–300 BCE) to pray for agricultural prosperity and health, and the haniwa variant were made in the Kofun period (300–538 CE) as ritual items for the powerful. The heart-shaped haniwa excavated from the Gobara site in Higashiagatsuma is a surprising example of the Jomon people’s refined sense for abstract art. However, the intricately detailed haniwa figure of a standing armored man is the only one to be designated a national treasure rather than an important cultural property. Gunma Prefecture is nicknamed “the land of haniwa”, and approximately 40% of the haniwa that have been designated as national treasures or national important cultural properties were unearthed there.

Right:Watanuki Kannonyama Tumulus Haniwa.

Collection of the Agency for Cultural Affairs / Photograph courtesy of Gunma Prefectural Museum of History

The Watanuki Tumulus Cluster lies in the southern part of Takasaki City (tumulus = a burial mound). This cluster includes the Kannonyama Tumulus, whose undisturbed stone chambers revealed tomb furnishings with a rich international flavor, including metalwork that tells of interaction with the Korean Peninsula, as well as haniwa (earthenware funerary figures). These are all precious items indicating the prosperity and power of the people who were buried there, and they are now designated as national treasures.

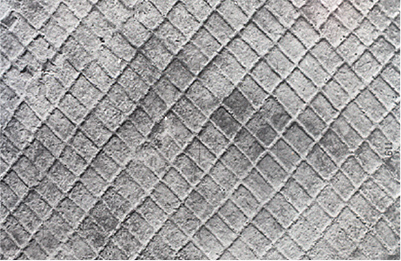

It is said that rice cultivation started in Gunma Prefecture in the middle of the Yayoi period (around 2nd century BC). While developing its own culture, Gunma strengthened its relationship with the Yamato administration and developed as the base of Yamato control over eastern Japan. In the Nara and Heian (794 –1185) periods, jori paddy fields (jori: a system of land subdivision by the state), were also developed.

This is the residence of a chieftain of the Kofun period found at the southern foot of Mt. Haruna. Approximately 86 meters on each side, the residence was surrounded by a moat with fences and stone walls, and the surrounding plateau is also home to the ruins of larger settlements and the remains of paddy fields. The residence is thought to have been the home of local ruling family representing the Seimo area, which surrounds the base of Mt. Haruna. Mitsudera I Ruins

Above: Restored model, photograph courtesy of the Kamitsukenosato Museum

Below: Overhang on the west side, photograph courtesy of Gunma Prefecture

This is the residence of a chieftain of the Kofun period found at the southern foot of Mt. Haruna. Approximately 86 meters on each side, the residence was surrounded by a moat with fences and stone walls, and the surrounding plateau is also home to the ruins of larger settlements and the remains of paddy fields. The residence is thought to have been the home of local ruling family representing the Seimo area, which surrounds the base of Mt. Haruna.

Two-thirds of Gunma Prefecture are comprised of areas morethan 500 meters above sea level. In the middle of the Edoperiod, 73% of the arable land area (87,500 ha) consisted ofupland cropland, the second highest after Oki Province (84%),due to the poor availability of water.

In the Edo period, new rice fields were developed by applyingconstruction and mining

techniques cultivated in the Sengokuperiod (1467–1615) for flood control and irrigation. A classicexample of this is the construction of Tenguiwa irrigationcanal, which irrigates the cultivated land on the southwardplateau west of the Tone River. Nagatomo Akimoto, lord of theSoja Domain, planned to draw water from upstream to theplateau over the Tone River, and

obtained permission from theShiroi Domain to do so. The canal was completed after threeyears of construction starting in 1601, and the yield of SojaDomain was 6,000 to 10,000 koku (a dry measure equivalent to180 L of rice used to determine land value and for taxation).Afterward, the waterway was extended by Tadatsugu Ina, thelocal governor of the shogunate

government, to enrich theTamamura region.

Changes in the amount of rice produced in the Edo period

| Kozuke Province (Feudal Gunma) | Japan | |

|---|---|---|

| 1598 | 496,000 koku | 18.51 million koku |

| 1834 |

637,000 koku Approximately 140,000 koku 28% increase |

30.56 million koku Approximately 12 million koku 65% increase |

* The lower rate of increase in Kozuke compared to the rest ofJapan during the Edo period indicates the difficulty ofsecuring a water supply there.

Since the prewar era, a combination of rice and barley farmingand sericulture was the common mode of agriculture in GunmaPrefecture. Until only recently, there were areas wherecultivation of farmland, let alone rice farming, had beendifficult, such as areas with weak water retention resultingfrom volcanic ash soil, and terrain on plateaus higher thanrivers.

Meanwhile, the hilly and mountainous areas of the northernpart of the prefecture are abundant with both water sourcesand hours of sunshine, and the climate is marked by asignificant temperature difference between day and night,producing tasty rice. The Numata region here stands alongsidethe Uonuma region of Niigata and the Iiyama region of Nagano,which together form “the triangle of good taste” inrecognition of the quality of their produce.

The Relationship between Lightning and Rice Cultivation

Summer lightning and dry winter winds are well-knownfeatures of Gunma’s climate. Japanese has a couple of wordsfor “lightning” that include ina, a word for rice: inazumaand inabikari. This is because lightning helps the riceharvest. The discharge of lightning combines nitrogen in theatmosphere with oxygen to form nitrogen oxides that plantscan absorb, increasing the amount of nitrogen that absorbsinto the rice paddies, leading to a good harvest of rice.Nitrogen is an essential component of plant growth, andsince there is a saying that “a flash of lightning makesrice grow a full inch”, one can see that our ancestors hadan empirical understanding of this. Shimenawa (sacredrice-straw ropes) are fitted with paper streamers that havea lightning motif, and perhaps these were intended asprayers for a good harvest.

Gunma Prefecture has a climate with many sunny daysthroughout the year, and due to its well-drained soil thatmakes it suitable for growing wheat, the cultivation ofwheat has flourished here since ancient times, making it oneof Japan’s leading production areas. Alongside okkirikomi,udon, yakimanju, and other traditional dishes, various otherlocal foods using wheat flour, such as pasta, yakisoba, andmonja, have spread across the people of the prefecture aspart of a “flour-based food culture”.

Photograph courtesyof Maebashi Convention and Visitors Bureau

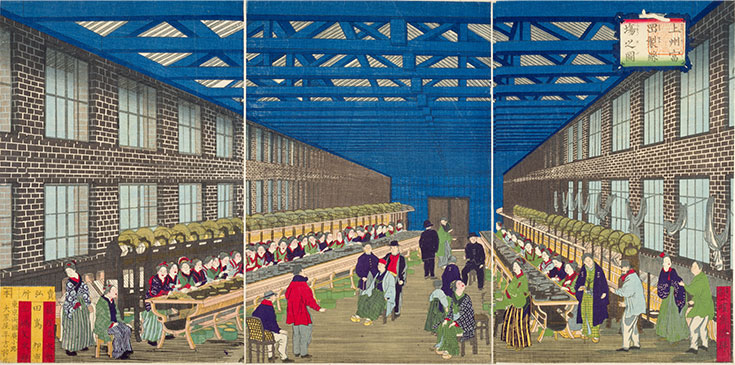

World Heritage Sites that supported the modern industry of the Meiji era

In 2016, four historic sites, including the Tomioka Silk Mill, were registered as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. This was in recognition of their technological innovation in modern mass production of raw silk, their role as forums for technological exchange between Japan and the world, and for their contributions to the development of silk culture around the world.

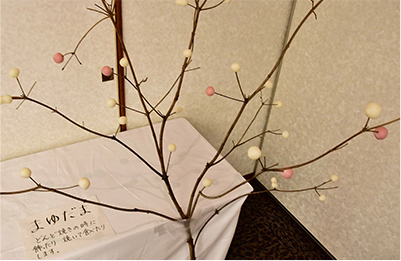

The healthy growth of silkworms requires warm temperatures, humidity, light and fresh air. During this period, more rational methods for raising silkworms were established according to the local climate and climate conditions.

This wind pit is a natural refrigerator in which silkworm eggs are preserved using natural cold air. Until wind pits like this came into use, sericulture was generally carried out once a year in the spring. But by adjusting the hatching time of eggs, sericulture could be conducted more frequently to increase the production of cocoons, supporting the increased demand for raw silk for export throughout the Meiji and Taisho (1912 –1926) eras. Wind pits were put into practical use in Nagano Prefecture by end of the Edo period, and it is said that there were more than 300 such pits nationwide once. Arafune Fuketsu had the largest capacity for silkworm egg storage in Japan.

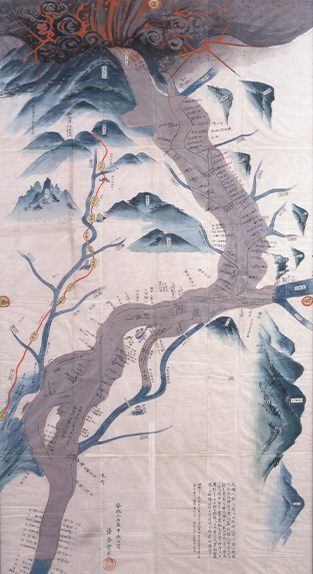

Mt. Haruna and Mt. Asama, which lie on the border with Nagano Prefecture, have had many major eruptions since ancient times. In particular, the terrible eruption of Mt. Asama on July 8, 1783 is recorded in detail, showing the extent of the damage.

“The whole mountain shook violently, [...] the first wave shook the earth like a terrible black ogre [...] the second wave threw mud and firestones hundreds of meters high [...] a million lightning bolts flashed in the darkness, and it was as if all of creation were collapsing.” (Asamayama yakedashi taihenki, “Record of the Disastrous Eruption of Mt. Asama”)

Pyroclastic flows and other avalanches of debris flowed into the Agatsuma River, forming volcanic mud flows that hit coastal villages and fields. Even after merging with the Tone River, the debris continued to surge toward Maebashi and Isesaki, killing more than 1,500 people and causing many deaths due to famine.

In response to this, the shogunate

and each domain responded quickly, and began payments of money and rice to the farmers affected by the damage in July. In August, the shogunate issued a plan to restore roads, bridges, and fields, and in the following New Year, ordered the Kumamoto Domain in Kyushu to provide assistance. It is said that 400 feudal retainers of Kumamoto clan went to the

site, and 100,000 ryo was invested to distribute relief money and rebuild infrastructure. There were also support activities led by village headmen and their associates, and donations from villages that had avoided the disaster. One can see a glimpse of how our ancestors were united by the spirit of mutual aid since ancient times in Japan, where major

natural disasters are frequent.

During the Edo period, Gunma Prefecture’s feudal predecessor Kozuke Province was a mixture of shogunate, hatamoto high-ranking samurai, and daimyo feudal lord territories. Many of the shogunate’s governors and hatamoto also resided in Edo, so not many officials were assigned to the local governor’s office. Furthermore, even the Maebashi Domain, the largest

daimyo territory, had a yield of only 150,000 koku of rice, including its enclaves. In other areas, there were many small clans with koku yields in the tens of thousands, and it can be said that governance in those areas was weak.

On the other hand, following the middle Edo period, many industries developed here, including sericulture, silk reeling,

textiles, hemp and leaf tobacco produced in the northwest, lumber and processed products from rich forests, wild vegetables, mushrooms, firewood and charcoal, and mineral resources, as well as tourism to Kusatsu Onsen, which was famous as a hot spring resort. Though the area was not blessed with rice crops, it had abundant supplementary industries and cash

income. As the rule of the samurai families was weak, they had no mechanisms to siphon off profits from these industries, and the commodity economy enriched the region, thereby fostering various cultures.

The strength of the people was demonstrated by the number of uprisings and village riots (about 1.5 times as many as in other areas throughout the Edo

period). Furthermore, the sericulture and textile industries could not have been established without the ability of the women. Female-led households fostered women’s independence and equality, giving rise to the famous local phrase kakaa tenka ni karakkaze—“wife’s rule and dry winds”, the female-led household and the dry wind being two hallmarks of the region.

In Kozuke Province, where upland farming played a central role instead of rice farming, sericulture, silk reeling, and the textile industry developed as supplementary businesses to keep households afloat after the middle of the Edo period. The high-grade silk fabric techniques of Nishijin in Kyoto were introduced to Kiryu in the 18th century, and due their proximity to Edo, a major consumer area, their reputation was such that Nishijin represented western Japanese silk, while Kiryu represented that of the east. Even today, Gunma Prefecture produces the largest amount of cocoons and raw silk in Japan, and is actively engaging with the future of the sericulture industry by developing original silkworm varieties and fluorescent silk cocoons.

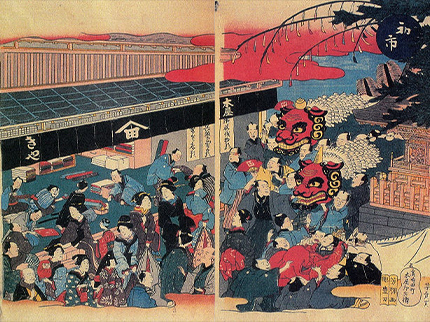

Constructed in 1819, the center of the stage has four mechanisms, including a revolving stage 7 m in diameter. It is the oldest revolving stage used for rural kabuki in Japan. At first, kabuki was mainly performed by Edo actors who traveled to participate, but it is said that from the middle of the 18th century, the farmers started their own truly local performances, jishibai, taking the roles of the actors themselves.

The economic development caused by the spread of commercial crops and convenient transportation led various intellectuals to visit from Edo and Kyoto. The high literacy rate, thanks to the spread of terakoya (temple elementary schools during the Edo period), allowed cultural activities such as haikai (seventeen-syllable verse), classical Chinese poetry, waka (poems of thirty-one syllables), learning, and literature to flourish among a wide range of people from merchants to farmers.

As cash began to circulate among the common people, specialist gamblers known as bakuto became rampant. To earn their money, they brought in young people and the homeless from the villages, secured territory to open a gambling parlor, and invited local townspeople, villagers, and travelers to gamble. The prevalence of these gamblers, the foremost of which was Chuji Kunisada, a vagrant from Kozuke Province, caused the shogunate to create a police agency whose jurisdiction crossed the borders of their administrative boundaries in Kanto.

This is one of Gunma’s three major Gion festivals. Records of this festival appear as far back as 1629. There, one can see the spectacular sight of a procession of sacred osakaki trees and sacred horses, with people using ritual salt to purify the way ahead of them.

This festival started when Nobuyuki Sanada, lord of the castle, built Suga-jinja Shrine in the early 17th century. Here, you can see the magnificent mikoshi and dashi floats.

This event is said to have started in 1604 as a pre-harvest festival to drive away harmful birds and insects and pray for a good harvest.

This dashi float festival is often called the best in Kanto, and is also known as “Abare Dashi” (Wild Dashi) because of its high-spirited energy.

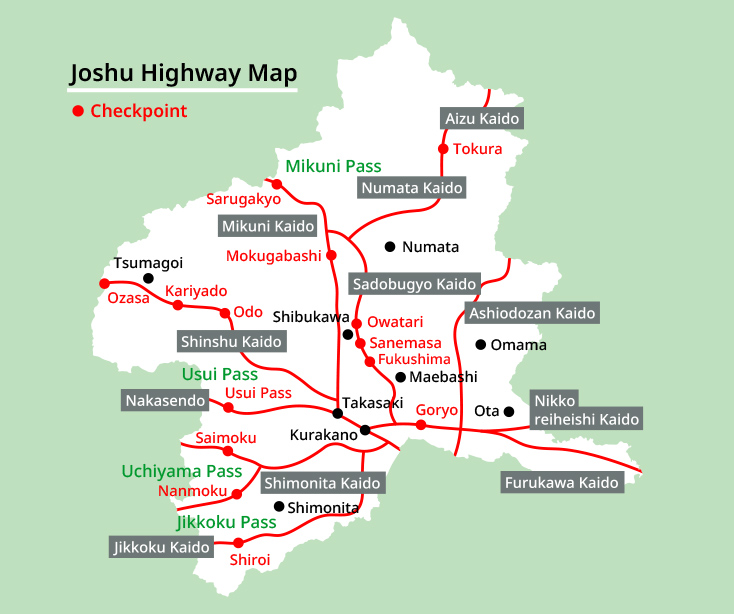

Highway Nodes to Various Regions

There were many highways in Kozuke Province, such as the Nakasendo highway, one of the five highways of the Edo period, and the Nikko Reiheishi Kaido highway, leading from Kyoto to Nikko Toshogu Shrine. These highways thrived with people and goods coming and going, and the post towns on the highways prospered.

Like the Tokaido highway, the Nakasendo

was an important highway connecting Edo and Kyoto. 7 of the 67 stations were in Kozuke Province. The Mikuni Kaido highway was the shortest route connecting Echigo and Sado, connecting the Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean sides of the island. The development of the Ashio Copper Mine resulted in the construction of the Ashio Copper Mine Highway, also known

as the Akagane Highway, which was the route for transporting copper for the shogunate to Edo.

The Shinshu Kaido, Shimonita Kaido, Jikkoku Kaido, Aizu Kaido, and Numata Kaido highways were developed as branch roads along the back roads of the Nakasendo highway, and various goods such as rice for annual tax, agricultural products, silk, hemp, tobacco, paper, firewood and charcoal, wood products, whetstones from Tozawa, sulfur and hot-spring sulfur

flowers, knick-knacks, and household goods were transported to Edo.

Mass transit at that time was supported by water transportation. Goods were actively transported between Kozuke Province and Edo through markets along the banks of the Tone River, also known by its nickname, Bando Taro, and by boat. The Agatsuma, Karasu, Kabura, Hirose, and Watarase

rivers, which join the Tone River, were also used, and it is said that there were about 40 riverbank markets.

Gunma Prefecture is located in the center of Japan, about 100 km from Tokyo. In modern times, four of Japan’s major highways pass through it: the Kanetsu, Joshinetsu, North Kanto, and Tohoku Expressways. In 1982, the Joetsu Shinkansen opened, followed by the Hokuriku Shinkansen route to Kanazawa in 2015. These developments established the prefecture as an important hub connecting Japan’s east and west, and between the Pacific and Sea of Japan sides.

*1 Reproduced from the “Gugutto Gunma Photo Studio” website. https://gunma-dc.net/

*2 Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries website

( https://www.maff.go.jp/j/keikaku/syokubunka/k_ryouri/search_menu/menu/32_9_gunma.html)

![[Gunma Local Cuisine]](../../img/kome_library/culture/06/text-title-page-09-pc.png)