From the period that rice-growing was brought to Japan approximately 3,000 years ago, right up to the present day, our ancestors toiled to find a way to grow a large amount of rice on narrow terrain.

Japan is described in the Kojiki, a record of the country’s development into a nation, as the “Country of Lush Reed Plains,” a reference to the bountiful growth of rice and an indication of how rice has symbolized Japan since ancient times.

In this corner, we will introduce you to Toyama’s diverse rice culture through its history, culture, and beautiful natural scenery.

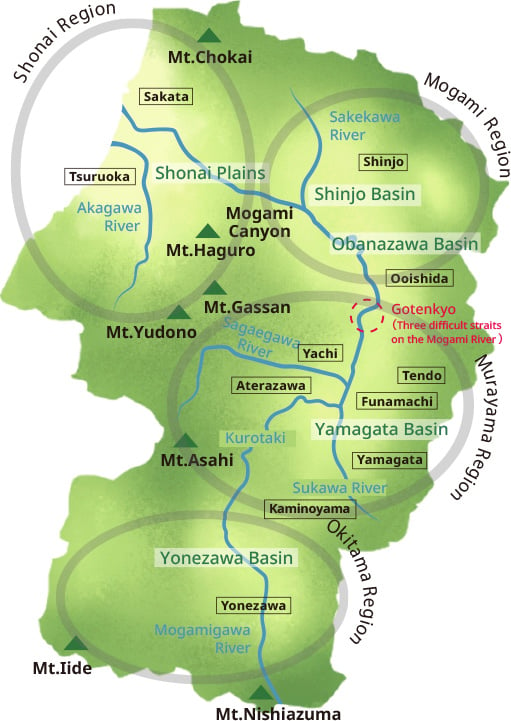

Mt. “Gassan,” the main peak of the Three Mountains of Dewa, which is located in the center of Yamagata Prefecture.

The area of Yamagata Prefecture is 930,000 ha (9th largest prefecture in Japan), 72% of which is forests. The Ou Mountain Range runs from north to south in the east, and parallel to it, from the center of the prefecture to the west, they extend from the Dewa Mountains to the Asahi Mountains and further to the Iide Mountains in the south. While the Mogami River, which is a combination of many tributaries originating from these mountains, forms the main river, it flows along the center of the prefecture forming the three basins of Yonezawa (Okitama region), Yamagata (Murayama region), and Shinjo (Mogami region) in the inland area, and the Shonai Plains downriver, which flows into the Sea of Japan.

The climate can be broadly divided into the coastal area facing the Sea of Japan and the inland area, with the inland area divided into the three regions of Okitama, Murayama, and Mogami.

The coastal area is centered on the Shonai Plains, which has an oceanic climate with frequent rain and humidity, strong northwest monsoons in winter, and snowstorms. Inland areas are generally warm with significant temperature differences. The Mogami region is centered on Shinjo City, which sees a lot of snow and frequent heavy rain in the summer. The Murayama region plains, centered on Yamagata City, generally have less rain and snow, but the mountainous areas of Gassan and the Asahi Mountains are some of the most rainy and snowy areas in Japan. The Okitama region, centered on Yonezawa City, has a mild climate, however the Azuma Mountains get heavy snow.

The Shinjo basin embraced all around by 1000m-class mountains, with the clear rivers from the huge primeval beech forest concentrated on the Sake River, the largest tributary of the Mogami River. The Shinjo basin and the Mukoumachi Basin is formed in the alluvial fan of the Mogami River. Because there is a lot of snow and forests occupy 80% of the area, the area is highly dependent on forestry. In terms of food culture, it is a region rich with the blessings of nature such as river fish, crabs, and various wild plants and foods from the mountains.

Photo provided by: Mogami Region Tourism Conference

In 1356, Kaneyori Shiba was dispatched to the feudal post of Ushu Kanrei and was based in Yamagata, which was then called Mogami, prompting a surname change to Mogami. During the Warring States period, Yoshiaki Mogami expanded the power of the Mogami and Shonai regions. With the reform of the Mogami clan (1622), the Torii clan became lords of the domain,

however their rule did not continue and the feudal lord would be replaced 13 times by the end of the Edo period. Even with this tremulous history, most of the Murayama area around Yamagata is said to be the largest territory in northern Japan.

The Murayama basin has alluvial soil blessed with water that is suitable for agriculture. Although mainly rice cultivation, safflowers and blue ramie* have been cultivated since ancient times, and fruit trees have been widely cultivated in recent years.

*Perennial plant Urticaceae, cultivated since ancient times. The plant fiber taken from the outer skin is as durable as fibers such as hemp.

In the 3rd year of the reign of Empress Jito (689), a young man from Ukitamu district (Okitama area) visited the capital for New Year, according to the Nihon Shoki (“The Chronicles of Japan,” the second-oldest book of classical Japanese history). It was before the founding of Dewa Province in 712, and it can be seen that the origin of Okitama is “Ukitamu,” which this area was known as in Ezo from ancient times.

The area is at the headwaters of the Mogami River and is a basin-shaped area surrounded by mountains on all sides, such as the Ou Mountain range, the Azuma Mountains, and the Iide Mountains. As the English traveler Isabella Bird, who visited Yonezawa in 1878, wrote in “Utopia of the East,” this place has been blessed with abundant natural resources since the Jomon period and has been brought up by a rich historical culture.

The fertile plains created by the accumulation of alluvium around deltas such as those of the Mogami River, Hinata River, Gakko River, and Aka River had large-scale irrigation weir construction and paddy field development projects from the end of the Muromachi period to the early Edo period. Currently, 90% of the area is rice paddies due to development

projects in the Meiji and Taisho eras cultivated land consolidation.

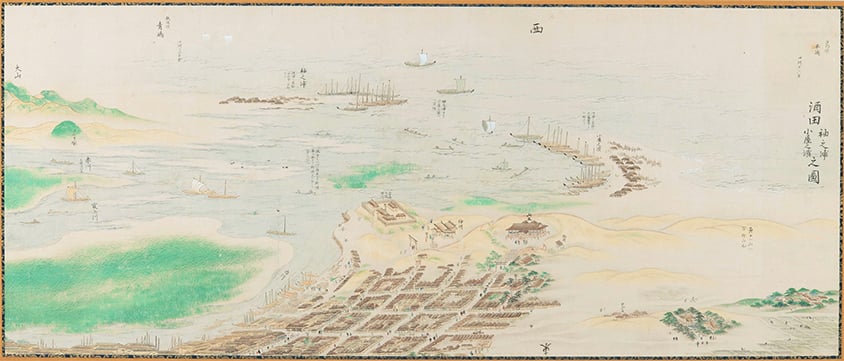

In 1672 with the development of the westward sea route in the Sea of Japan by Zuiken Kawamura, “Shonai Rice” expanded its sales channels to large consumption areas such as Osaka and Edo. In addition, this route brought about high culture that remains everywhere.

The foot of Mt. Gassan sees a lot of snow, making the area unsuitable for rice cultivation, and the people are involved in both farming and mountain work, and live religious lives.

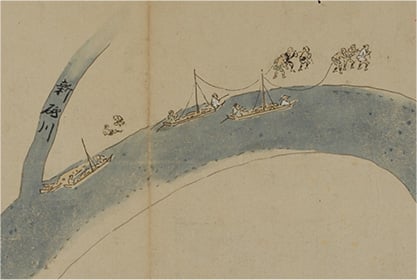

The Mogami River connects these four distinct regions. The Mogami River has a long history of being used as a transportation route. It was written about in the Kokin Wakashu anthology of poetry in the early Heian period, and it is said that Minamoto no Yoshitsune traveled upriver by boat when he relocated to Hiraizumi.

Full-scale shipping development on the Mogami River started in the times of the Mogami clan, and the three most dangerous spots were excavated and riverbanks were set up (Oishida, Funamachi). During the Genroku era, the Yonezawa Domain's merchant, Kyuzaemon Nishimura, promoted development upriver between Okitama and Murayama, such as the excavation of Kurotaki, and the Yonezawa Domain's boathouse was established in Aterazawa.

Photo provided by: Yamagata Office of River and National Highway.

Photo provided by: Shinjo River Office.

A scenic project reminiscent of the scenery of the time when river transportation thrived.

In this way, the distribution and economic pipelines that connect Yamagata Prefecture’s four regions was completed. The supplies that went downstream at that time were mainly shiromai rice of the shogunate territory and annual tributes of rice from various domains, as well as special products such as safflower, blue ramie, tobacco, wax, and lacquer, and supplies that went upriver were mainly salt, dried fish, salted fish, used clothing, cotton, fancy goods and other daily consumables.

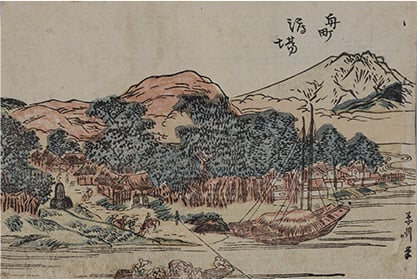

Depicts a Hirata ship, which played the leading role in Mogami River water transport, at anchor.

It took four times as long to go up the river by boat. Boats are usually towed by sailors, but when loaded with goods the boats are heavy and tow laborers were hired.

Photo courtesy of the Yamagata Prefectural Museum.

The specialty safflower was used as a dye, and the blue ramie was used as a raw material for textiles.

Cookies from the Jomon period

Yamagata Prefecture, which has the largest Beech forest in Japan, is thought to have been covered with deciduous broad-leaved forests that provided abundant food even during the Jomon period. Eighty percent of the Jomon period population was distributed in eastern Japan. The reason is that the deciduous broad-leaved forests contained more major foods such as walnuts, chestnuts, horse chestnuts, and oak nuts, which are richer in fat than the nuts in the laurel forest zones of western Japan. Also, rivers in eastern Japan had salmon and trout. With the background of such abundance, the remains of the Jomon period people have been confirmed all over the prefecture.

from Ondashi Heritage site (early Jomon period)”

Photo provided by:

Ukitamu Fudoki no Oka Archaeological Museum.

Cookie-like carbides from the Jomon period have been excavated from about 30 archaeological sites in central eastern Japan. The Ondashi Heritage site in Takahata Town is characterized by a whirlpool pattern on the surface. As a result of analysis, it was found that it was made mainly from chestnut and walnut powder.

In this region, it seems that Onga River pottery was transmitted from Kitakyushu via the Sea of Japan route in the early Yayoi period, and paddy rice cultivation also began at the same time. The place name Okitama appears in the “Nihon Shoki”, and place names indicating the ancient jori system of land division remain. Since the establishment of Dewa Province in 712, the system of governing the regions was established and regional development promoted.

The Shonai area had a small settled population, so within the imperial court an opinion was given that “The land is simple and the fertile fields are large, so people should be relocated there and the land should be preserved” and over a thousand households migrated from Okitama, Mogami Nigun and Owari, Shinano, Ueno, Echizen, and Echigo provinces. The development of the Shonai Plains was promoted as a national project, and its foundation was established in the early Nara period.

Photo provided by: Yamagata Prefectural Center for Archaeological Research

For the development of new rice fields in the alluvial fan of a large river, the presence of a stable ruling lord with a large labor force and abundant funds was essential. Development in Yamagata proceed into the 17th century after the reign of the Mogami clan.

After the Battle of Sekigahara, Yoshiaki Mogami, who became a 570,000 koku Daimyo, began full-scale hydrological control and weir excavation in the Shonai Plains. The excavation of the Inaba Weir was started for irrigation on the right bank of the Aka River (1607), and the difficult construction of the Kitadate Weir began in 1612. With the completion of the

latter, paddy fields in 88 villages were irrigated, and the kokudaka (the system for determining land value in terms of rice) increased from 3,000 koku to 30,000 koku.

Sakata City Museum collection.

Tadakatsu Sakai, who became the lord of the Shonai Domain after Mogami, also encouraged rice cultivation. This spurred an increase in production and Shonai became known throughout the country as a major rice producing area. In 1649, a komeza rice merchant trade association was established in Sakata, which became known as a center of rice trading alongside Dojima in Osaka and Kanazawa in Kaga. In 1672, when Edo was hit by a great famine, the shogunate ordered Zuiken Kawamura to open a “westward route” and bring a large amount of rice from the Shonai Plains to Edo. The state of Sakata, which had become extremely prosperous as a port for shipping rice, is also described in Saikaku Ihara's “The Eternal Storehouse of Japan.”

The prosperity of Abumiya, one of the leading figures of the 36 prominent people of Sakata, is also introduced in Saikaku Ihara's “The Eternal Storehouse of Japan.”

The development of new rice fields and hydrological control proceed in other regions as well. Farmland in the Yonezawa Plains was 16,696 ha in 1721, but increased to 21,709 ha during the Kansei era, 1789-1801, around the time of Yozan Uesugi. Farmland by the early Meiji era was 23,084 ha, only about 1,400 ha more than in the Kansei era, so it may be said that this basin was almost fully developed during Yozan Uesugi’s time.

Rice cultivation in the early Meiji era was centered on “wet paddy rice farming.” Although it was easy to work manually by constantly filling the paddies with water, soil improvement had not progressed and so yield could not be increased. “Dry field horse-plowing” started in the late Edo period in Kyushu. Introduction was attempted in the middle of second decade of the Meiji era because this method can cultivate the soil deeply using horse power, which increases the effect of fertilizer and the yield, but it was difficult to disseminate due to the conservative nature of the locality.

Photo provided by: Tsuruoka City Folk Museum.

In 1890, Yasukichi Hirata, a progressive farmer in Tsuruoka, invited an agricultural teacher from Fukuoka Prefecture to introduce the technology, and the landowner Honma family founded the Honma Farm and invited Fukuoka's agricultural teacher Jihachiro Isa. By the end of the Meiji era, the method became popular in about 80% of Shonai because new techniques and farming methods such as harrow cultivation and dry rice field farming, as well as seedling cost and fertilizer improvements, were taught to the Honma family, and “land managers” were taught to teach these methods to peasants.

In addition, the Shonai region has produced many private breeders since the Meiji era. This was not only because of the need for breeding suitable for new farming methods, but also a manifestation of the farmers' passion for rice, which has been passed down since the feudal era. One of these breeders was Kameji Abe, who was born in Shonai Town (formerly Amarume Town) as the eldest son of a farmer. From the end of the Meiji era to the Taisho era, “Kamenoo” rice, bred by Kameji, was cultivated not only in Japan but also on the Korean Peninsula and in Taiwan, and has become one of the three excellent varieties of Japanese paddy rice. Today, Kamenoo is cultivated in small quantities, but varieties such as “Koshihikari,” “Sasanishiki,” “Hitomebore,” “Akitakomachi,” and “Haenuki” are its descendants.

Photo provided by: Wagou no Sato Society.

A rice storage warehouse built in 1893. The structure of rice that is loaded and unloaded without being exposed to rain or wind, the elaborate air-conditioning control in the warehouse, and the strict selection and examination of the warehoused rice has produced “Sankyo Rice,” which is said to be the best in Japan in the central market.

Until the early Showa era, rice was the main food in Yamagata prefecture. As a commercial crop, since the Meiji era, silkworm culture has flourished and, because it is a snowy area and not a suitable place for wheat, rice predator crops were on the scale of intercropping. Daikon radish, turnip, eggplant, and cucumber were pickled to be stored during winter

and pre-harvest, and taro and potatoes gave birth to events such as the “Imonikai.”

Since there are few crops other than rice, many foods are collected from the mountains and rivers, and you can also see the dishes related to seasonal events.

- Spring: Wild plants, bamboo shoots

- Autumn: Chestnuts, walnuts, horse chestnuts and other nuts, mushrooms

- Meat from birds and animals

- Salmon, Ayu, minnows, river crabs

- From the snow-melt filled rice fields in early spring, spiral shellfish, and pond loaches from summer to winter, and grasshoppers in autumn

(Mogami region)

(Murayama mountains areas)

with vinegar and miso and served at peach festivals.

-

“Silkworm mochi”

“Silkworm mochi” (Okitama region) is preferred on special days, and in the Okitama region it is known as “Usu no Hata Mochi” (meaning “freshly pounded” mochi).

-

“New Year's Ozoni

using round mochi.”

In the Shonai region, mochi is influenced by the Kansai food culture brought in by the Kitamaebune shipping route, such as round mochi, morning rice porridge, and dried whale.

-

“Koinoumani”

In the Okitama region, carp are kept in garden ponds and ginseng is planted in hedge fences, which Yozan Uesugi promoted as famine foods in case of emergency.

All photos are from the Rural Culture Association Japan.

The Three Mountains of Dewa (Mt. Gassan, Mt. Yudono, Mt. Haguro) is mecca for Shugendo*, which has spread its faith not only in the Tohoku region but also in the Kanto and Hokuriku regions. Its founder is said to be Prince Hachiko, the son of Emperor Sushun. Its origins stem from the nature worship from the Jomon period, and what is scared for Mt. Gassan is the mountain’s form itself, Mt. Yudono as a giant rock from which hot water springs, and Mt. Haguro’s Kagamigaike Pond on the summit. During the Edo period, the trailheads called Happo Nanakuchi and the roads leading to them were full of worshipers, and it is said that there were as many as 157,000 worshipers in 1733.

The vegetarian foods offered in the temple towns were the foods of mountain priests, who were originally self-sufficient. In olden days, what was harvested was eaten raw on the same day, but gradually cooking methods were also adopted. Looking for ways to make foods that cannot be eaten raw because of their strong lye delicious, it seems such foods began to be preserved by salting and drying them, and they were offered to guests.

* “Shugendo” is a type of mountain worship in which religious austerities are practiced in the mountains.

uses tofu, Gassan bamboo shoots, wild plants and mushrooms abundantly.

Photo is from the Rural Culture Association Japan.

In Yamagata Prefecture, there are many traditional vegetables that local people have protected and inherited from ancient times. It is said that there are more than 150 varieties of traditional crops, including those other than vegetables.

-

“Mogami red garlic,”

(Photo provided by: Yamagata Prefecture)

Jingoemon potato

(Photo provided by: Yamagata Prefecture) -

Yukina

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group)

Saltwort

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group) -

Mottenohoka

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group)

Zao pumpkin

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group) -

Dadacha-mame

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group)

Atsumikabu

(Photo provided by: Delicious Yamagata Promotion Group)

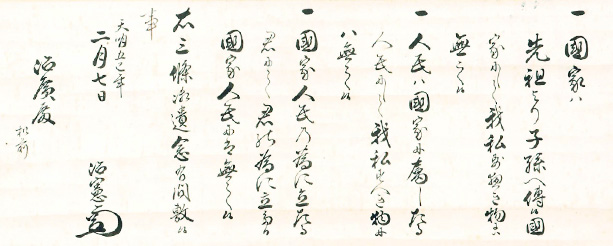

The Uesugi clan's reign in Yonezawa continued for 267 years from 1600. Among the Uesugi daimyo, Yozan Uesugi, who became the lord of the Yonezawa Domain in 1767, is a famous man who encouraged the breeding industry, revitalized rural areas, and made efforts to be frugal and rebuild the domain’s administration.

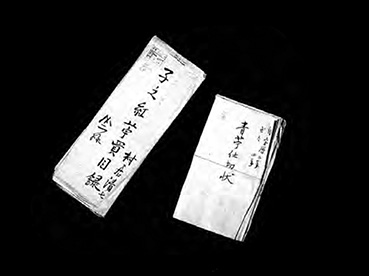

Yoshimasa Nozoki, who assisted Yozan, distributed “Katemono,” which describes famine food, to the territory as a measure against famine. This was an introduction to emergency foods and preserved foods that are eaten with cereals, but it also describes the names and cooking methods for 82 varieties of wild grass, how to make miso and soy sauce, and how to

store fish and bird and animal meat. This booklet was distributed within the domain and is said to have been very useful during the Great Tenpo Famine, and also in the food crisis during the Greater East Asian War.

Photo provided by: Yonezawa City (Uesugi Museum)

National Diet Library collection

A three-article admonition sent when the family estate was handed over to Haruhiro. It was full of a democratic spirit that was unheard of in the feudal era, and even John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, named Yozan as an ideal politician.

Imoni is made by boiling water in a large pot, to which is added taro, green onions, konjac, and beef, and is seasoned with soy sauce. Before WWII, the luxurious imoni of today could only be eaten by businessmen with large shops in the town and landowners in rural areas, and it seems that ordinary people used whale meat with potatoes until postwar life improved.

Imoni, which started as social events for junior high school and high school students from the end of the Meiji era, became popular among a wide range of generations after the war, and riverbed areas became full of them. This may be rooted in the custom of playing in the fields in the area from ancient times, such as the event “Takaiyama” to pick up Ta-no-Kami (spirits believed to observe the harvest of rice plants or to bring a good harvest) in the local mountains on April 17th of the old lunar calendar.

Photo provided by: Imonikai Office.

A massive imoni party where about 30,000 meals are boiled in a large pot of over 6 m, which is held every September at the Mamigasaki Kasen riverbed in Yamagata City.

Japan's largest ramen consumption

Looking at the number of shops per 100,000 people, Yamagata Prefecture is the undisputed number one. According to a household survey by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Yamagata City spends the most on ramen in Japan.

Yamagata is also a place for soba, and there are numerous soba restaurants, many of which also offer ramen. It is very hot in summer, even once having recorded the highest temperature in Japan. That is where chilled ramen was born. By removing the fat from the pork and chicken bones that hardens when cooled, a refreshing and delicious soup was created.

During the post-war era of food shortages, ramen was cheap and high in calories and became regarded as a small treat, so it seems that ramen is also offered as hospitality to guests.

The coast of the Shonai area was thick with forests until the Middle Ages. However, it was devastated by the battles during the Warring States period and logging for firewood in salt production, and in the Yuza District, houses, roads, fields, river weirs, etc., were all filled with sand during the Shoho era, 1644-48.

In 1707, the clan administration reform imposed restrictions on deforestation, and ancestors entrusted with planting trees as “planters” by the domain began planting black pine trees. During the Enkyo era, 1744-48, the situation failed to improve to the point where several villages were lost.

At the request of the domain, in 1746, the sake brewer’s Tozaemon Sato and his son Tozo embarked on a tree planting business. For 50 years until Tozo died at the age of 80 in 1797, they sacrificed their family business and devoted their lives to the tree planting business. The Honma family, wealthy merchants in Sakata, also started an afforestation business in 1758 when headed by their third generation head Mitsuoka, and pine seedlings finally began to take root in 1762. About 60 years later, a large pine forest was formed on the north bank of the Mogami River. Thanks to the efforts of many ancestors who worked with an indomitable spirit, the eastern sand dunes became stable in the middle of the Edo period, and the scope of construction was expanded to the western section (coastline).

“A private house buried in sand and tree planting the 1940s”

Source: Tohoku Regional Forest Office website

(https://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/tohoku/syo/syonai/gaiyou/syonogaiyou.html)

Before and after World War II, there were times when the coastal forests were devastated due to neglect, however tree planting projects were resumed in 1951, and 584ha of trees was planted by 1979, 32 years later. As of 2017, the area of artificial forests in the coastal forest has reached 674ha.

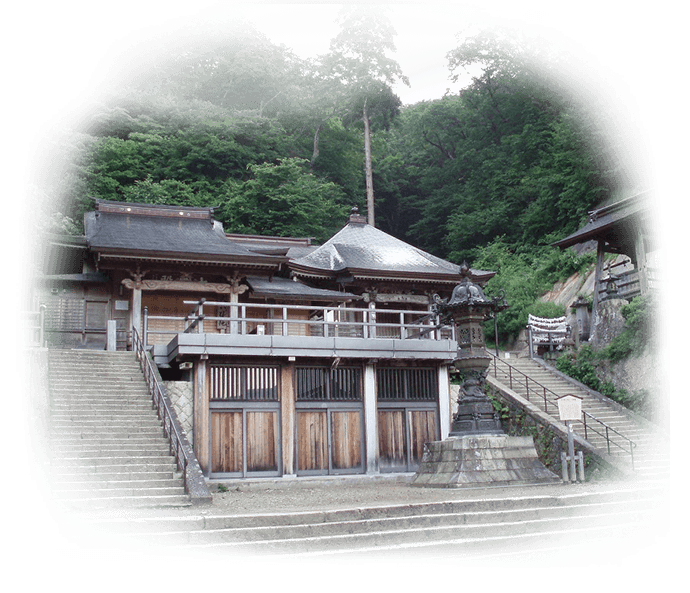

Ennin (Jikaku Daishi) is said to have founded the Risshaku Temple in 860 at the behest of Emperor Seiwa. Along with the Jion Temple, it is an ancient temple known for the phrase “ah this silence, sinking into the rocks, voice of cicada" by the poet Basho Matsuo.

In this region, it is customary for relatives to put some of the ashes of their dead, particularly their teeth, into the ossuary of the “Oku-no-In” (the summit) for memorial services. From ancient times, the Japanese believed that they would go to a nearby mountain after death, where they would protect the safety of their descendants and community. The soul

can climb higher mountains through memorial services and festivals, finally ascending to heaven. It was also said that neglecting memorial services would cause disease epidemics and natural disasters, as well as cold damage that would ruin rice cultivation.

” (Yamagata City): Yamadera Tourism Association

There are many performing arts that have been handed down in various parts of Yamagata prefecture due to the strong faith of the people and enthusiasm to pass them down to the next generation. Life and festivals were united to maintain the village communities. This is the traditional climate of rural society since the early modern period, centered on agriculture, that has been maintained for a long time.

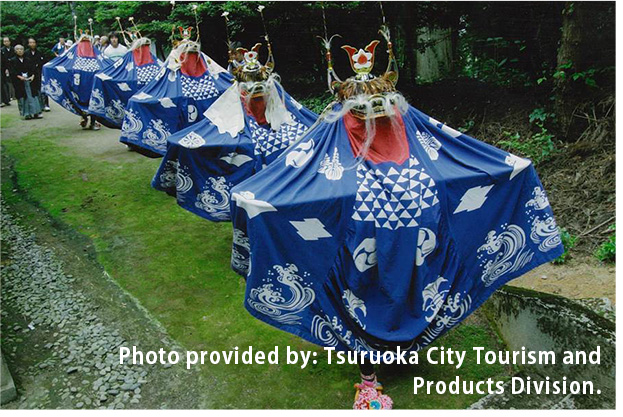

Kurokawa Noh has been passed down for more than 500 years by the parishioners (farmers) of the Kasuga Shrine. It follows the tradition of Sarugaku, which was completed by Zeami, but it is a folk performing art unique to the Shonai region that has inherited its own tradition without belonging to any Noh school. Songs that were discontinued and performances

that have not been inherited in the five schools (Kanze, Hosho, Kongo, Konparu, and Kita) still exist and are being transmitted.

Since it is also a dedication ritual, when performing Noh the priest first prays for the permission of the great gods such as Kasuga-no-Kami and Ujigami, and then Noh is performed. Therefore, it is customary that the Noh actors are not professional Noh performers, but priests of Kasuga Shrine, including the musicians.

It is recorded in old records that at the time of the opening of Risshaku Temple in 860, Masateru Echizen no Kami Hayashi, a musician of Shitenno Temple in Osaka City, went to the eastern country according to Ennin and conveyed the bugaku of the Shitennoji Temple to Yamadera. After that, the descendants provided bugaku music every year at Yamadera. They

moved to Jion Temple (Sagae City) during the Muromachi period and then to Yachi in the early Edo period, where they were responsible for the bugaku for Yamadera, Jion Temple, and the Yachi Hachimangu Shrine.

Since Hayashike Bugaku went to rural areas early, it is said that it was less affected by the reform of the music system (Japanification) after the middle of the Heian period, and that it retains the remnants of the Silk Road. They perform at Risshaku Temple's special memorial services, Jion Temple's All the Buddhist Sutras Society event on May 5th, and

Yachi Hachimangu Shrine’s Annual Grand Festival in September.

Sugisawa Hiyama is a bangaku that is handed down in the Sugisawa district of Yuza Town. Bangaku is a kagura ritual ceremonial dance performed by Yamabushi and is dedicated to the Kumano Shrine. There are no clear records of its origin, but it is believed to date back to at least the Kamakura period, as it retains its old appearance since before Noh was complete. It is believed that what was performed by trainees during the prosperity of the Chokai Shugen religion was eventually handed down to the villagers as it declined. There is a theory that there was a time when Mt. Chokai was regarded as the “Hiyama (Sun Mountain)” for Gassan, and it was named “Hiyama Bangaku” in that sense.

A traditional event in which a young man wearing a bird-shaped straw cape becomes the Kasedori and parades through the town. Cold water is sprinkled with prayers for a good harvest and prosperous business.

An event held during the Lunar New Year as an advance blessing for a good harvest by simulating farming.

A ceremony for the repose of a departed soul, which is widely seen in the Tohoku region. Unlike the “lion dance” introduced in the Nara period, it uses the same pronunciation for lion (Shishi) to mean “wild boar” or “deer.”

Somokuto

Somokuto, which are often found in the Okitama region, are stone pagodas built with feelings of gratitude and as a memorial for felled trees, and said to be unique to Okitama. The oldest known Somokuto is the “Shiojidaira Somokuto” built in 1780, and the inscription says, “Plant Memorial Tower.”

(Yonezawa City)

Photo provided by: Yamagata Prefecture