Bushu Yokohama Ōsetsujo nioite Kyō-ō no Zu, Yokohama City Central Library collection

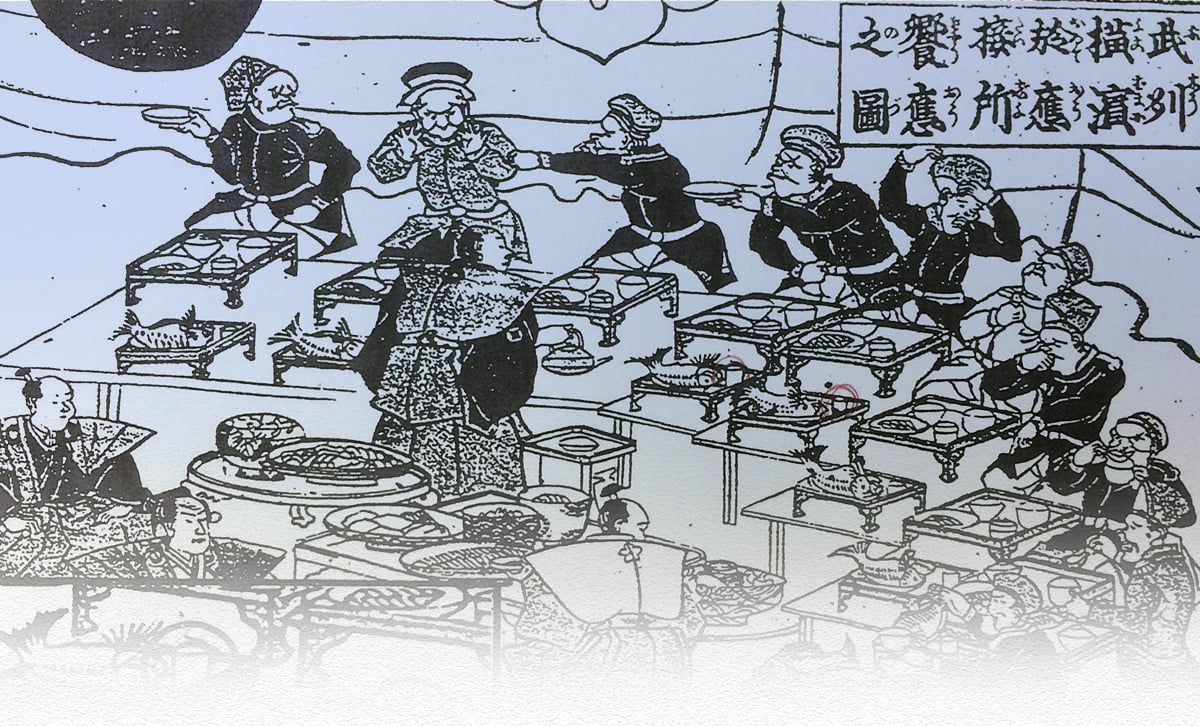

Honzen Ryori first appeared in the Muromachi Period as the style of meal served to guests in the samurai warrior classes and it continued to develop in the Edo Period. There are several styles of honzen ryori, all of which have the honzen, or main tray, at the center. How they differ is in the number of soups sand side dishes, such as the one soup/three side dishes style, the two soups/five dishes style, and the three soups/seven dishes style. The greater the number of zen, the small tables on which the dishes are served, the more prestigious the occasion.

Azuchi Kyō-ō Zen (Jūgo-Nichi Ochitsuki Zen),

Azuchi-cho Bungei no Sato Shinko Jigyodan collection

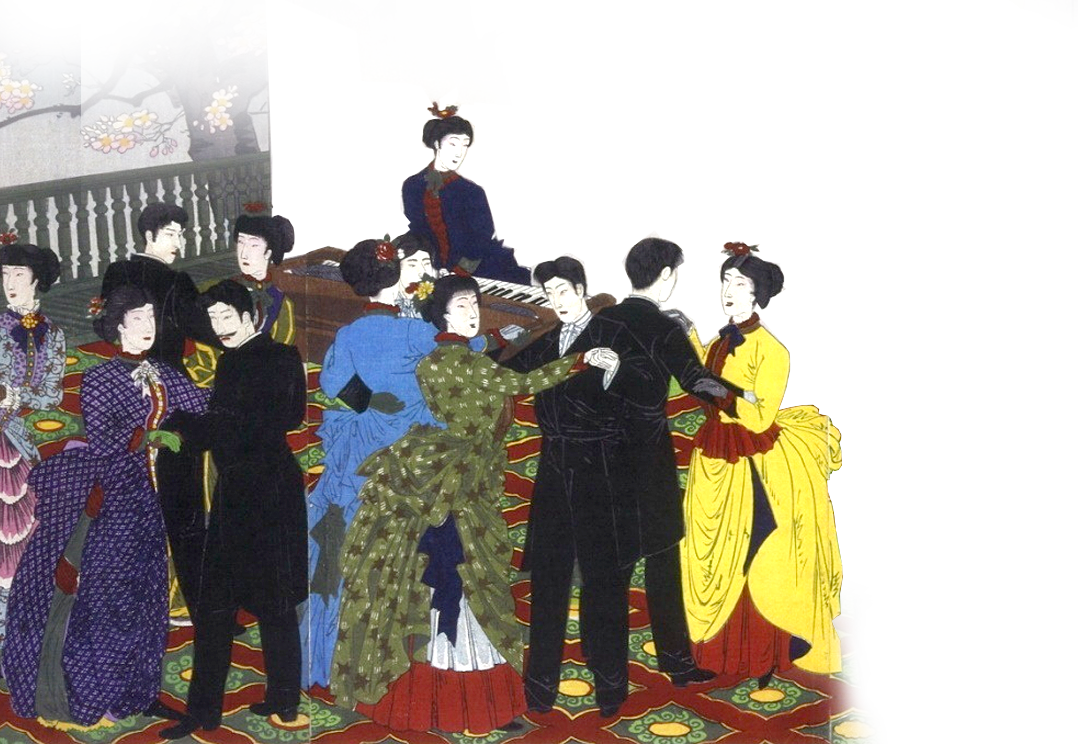

After Japan was opened to the outside world at the end of the Shogunate, Japan was faced with the need to entertain the many foreigners coming to Japan. In the beginning, these visitors were served Honzen Ryori, the traditional formal cuisine for banquets. According to records of the time, however, this style was not necessarily well received by the foreign visitors.

Yokohama Ōsetsujo Hizu, Nagano City Board of Education, The Sanada Treasures Museum collection

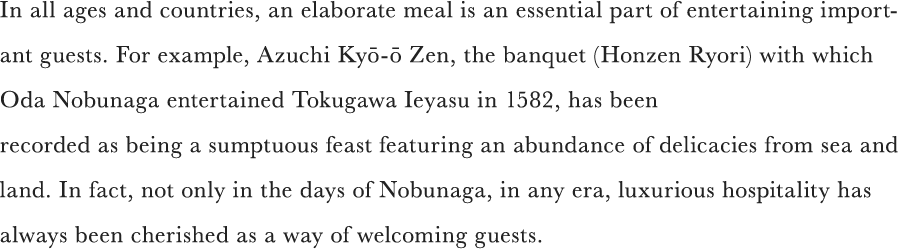

In 1854, when talks were held in Yokohama for the conclusion of the Convention of Peace and Amity between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan, Japan hosted a celebratory banquet for Commodore Perry and his delegation. At the banquet, it is said that the guests were presented with a sumptuous Honzen Ryori feast, featuring an abundance of delicacies from sea and land. However, despite the huge expense that was put toward this banquet, it is said that, unfortunately, the food did not appear to please Commodore Perry and his party.

Photo courtesy of Miketsukuni Wakasa Obama Food Culture Museum, supervised by Ayao Okumura

According to the records, Honzen Ryori, with three soups and seven side dishes, was served at a banquet held for a Russian delegation led by Admiral Putyatin in Nagasaki in 1853. However, on this occasion as well, the reaction of the foreign visitors was not very favorable. They are recorded as commenting that the “black, thick soup” (probably miso soup) was “delicious,” but the clear fish soup “seemed just like hot water and did not taste good.” Similar to the reaction to the banquet for the Perry delegation, the lighter soups served at the banquet probably did not suit the palate of foreigners who were used to food with a strong flavor.

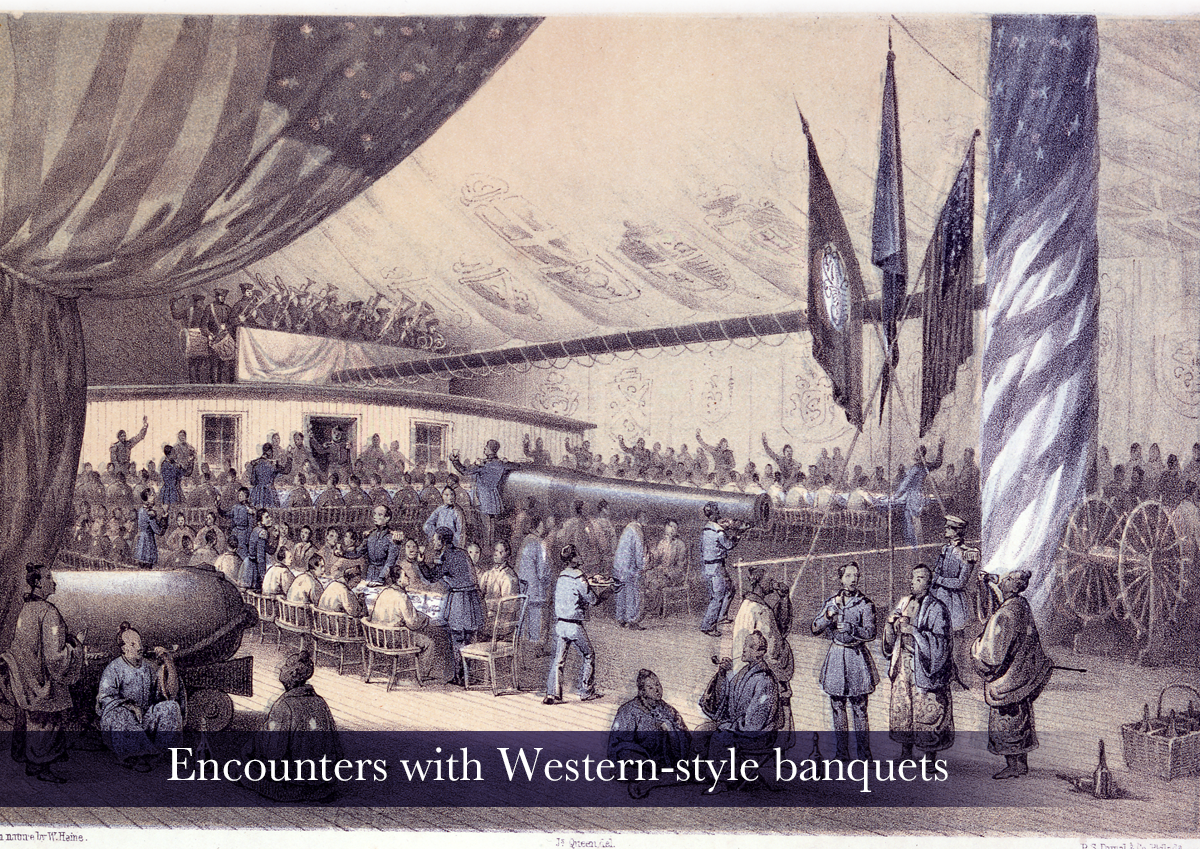

Scene from the banquet held on the deck

of the USS Powhatan,

Yokohama Archives of History collection

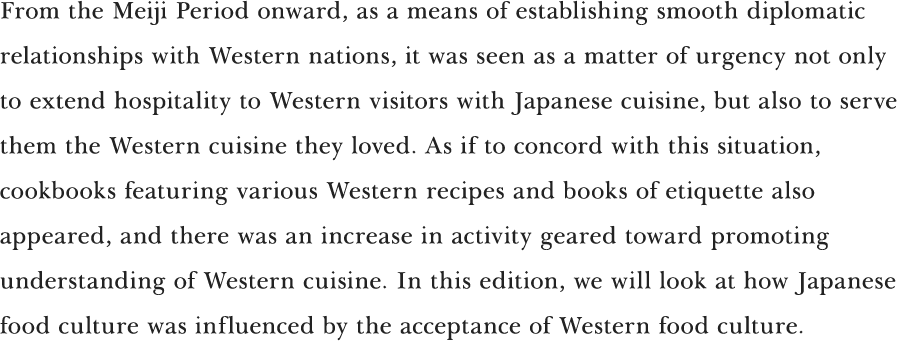

The first Japanese to experience the Western style of banquet in the Bakumatsu period were the bureaucrats of the Shogunate who engaged in the negotiations for the Convention of Peace and Amity with Commodore Perry and his delegation.

On March 27, 1854, a month and a half after the Yokohama banquet, Commodore Perry hosted a dinner party on the USS Powhatan, to which he invited some 70 Japanese guests, including Hayashi Daigaku-no-kami Akira, the scholar-diplomat who led the Japanese side in the negotiations. It is recorded that the guests were served a sumptuous feast of Western food, from soup, salted ham, and a roast of ox tongue, to desserts such as fruit punch, sugar candies, and milk sweets. The Shogunate bureaucrats were very curious and politely partook of all of the dishes. It is recorded that they wrapped any food left over in their kaishi (a piece of paper folded and tucked into the front of their kimono) to take home with them. This custom of taking leftovers home apparently seemed odd to the foreigners of the time, with various documents recording the occasion deriding it as a target of ridicule.

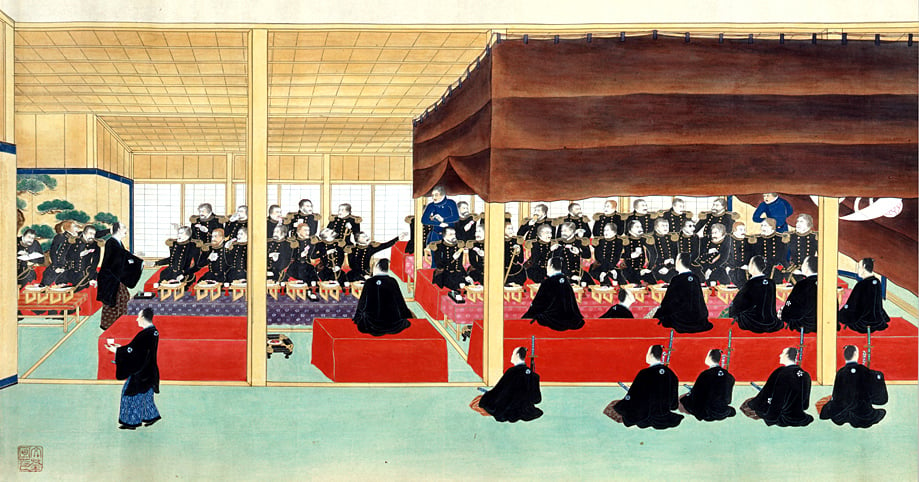

From ancient times, social meeting places used to entertain honored visitors from overseas have played an important role as a gateway to cultural exchange. This history can be traced as far back as the Nara and Heian Periods (7th to 11th centuries). It is recorded that guest palaces, known as kōrōkan, existed in Hakata, Kyoto, and other cities to entertain diplomatic missions and merchants from the continent.

In Japan, after it was opened to the world, there were many more opportunities to host banquets and dinners for diplomatic envoys and other dignitaries from the West. In 1873, it was officially made compulsory to serve French cuisine at such occasions.

Photo courtesy of Miketsukuni Wakasa Obama Food Culture Museum, supervised by Ayao Okumura

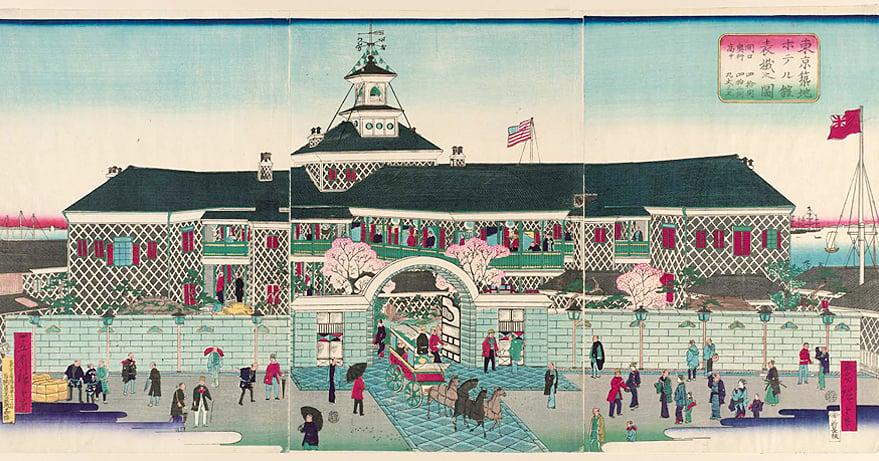

In 1883, construction was completed of the Rokumeikan, a place to entertain state guests and diplomats from overseas. As well as its opulent ballroom, the Rokumeikan also housed accommodation facilities, a bar, and other facilities, and it served as a kind of luxury hotel. Of course, the banquets served there were based on the formal French style.

In 1890, at the urging of Japan’s political and business circles, a new guest house, the Imperial Hotel, was born. Both then and now, the Imperial Hotel has continued to play an important role in public diplomacy.

In 1858, with the conclusion of treaties of amity and commerce with various countries, many foreigners started to visit Japan. In response to this situation, the construction of hotels suitable for receiving Western dignitaries became a matter of urgency, leading to the establishment of the Yokohama Hotel in 1860, the Hyogo Hotel in 1871, and the Tsukiji Hotel in 1868. In addition to accommodation, these hotels offered restaurants, bars, entertainment rooms (billiards, etc.) and other facilities.

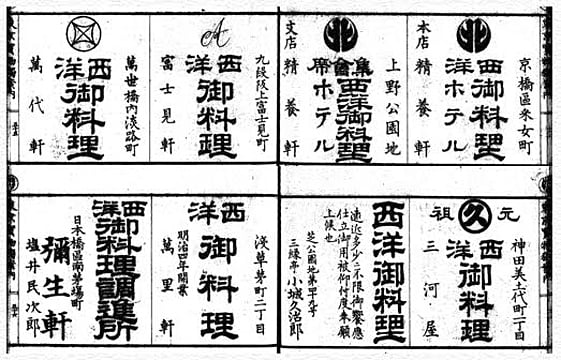

A succession of restaurants serving Western cuisine also opened in the foreign concessions, such as Ryorin-tei in Nagasaki in 1863, Goto-ken in Hakodate in 1879, and Italia-ken in Niigata in 1881. Meanwhile, in Tokyo as well, from the very first year of the Meiji Period, some of the leading Western-style restaurants of the era opened one by one, including Mikawaya in Kanda in 1867, Seiyo-ken in Tsukiji in 1872, and Seiyo-ken in Ueno (1876). Goto-ken and Ueno Seiyo-ken are still in business today.

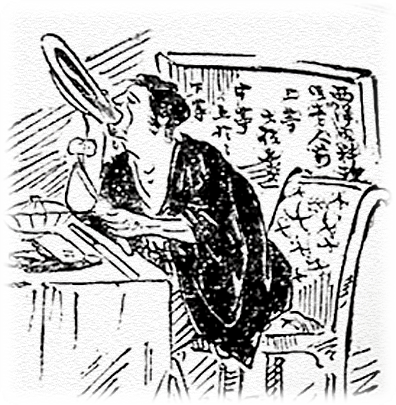

Even so, the fact remained that many Japanese were bewildered by Western manners. Literature from that period contain many references to how Japanese people struggled with this new way of dining. From the tragedy of someone who was unaccustomed to using a knife and fork cutting his mouth while eating, to the unexpected occurrences of diners attempting to drink the soup directly from the bowl and spilling it all over themselves from chest to lap. These anecdotes show that many Japanese people at the time found it very difficult to understand these new Western manners.

Many guidebooks explaining Western manners were published in an effort to rectify the situation. Bureaucrats and military personnel, in particular, apparently sought out these books to obtain the knowledge they needed to forge relationships with foreigners, to avoid embarrassment in diplomatic situations.

Western cuisine

expanding

to the world of

ordinary people

Although Western cuisine was rapidly accepted in Japan after the opening of the country, it remained unattainable for ordinary people. In the early Meiji Period, only the privileged class were able to taste Western cuisine.

By late Meiji, however, more opportunities started to appear for commoners to enjoy it, albeit at a slower pace. Nevertheless, it was extremely difficult for them to procure western ingredients and eating utensils, both of which were very expensive. That situation prompted ordinary people to adapt Western cuisine to Japanese ingredients and cooking methods. Using such “fusion” methods, they proposed new tastes that suited the Japanese palate. This prompted the emergence of a new, Japanese-style cuisine known as yoshoku.

Within this trend, tonkatsu (breaded and deep-fried pork cutlet), raisu karee (curry and rice), and korokke (croquette), acquired the status of the three classic Yoshoku dishes that people most wanted to eat. All three of these yoshoku dishes have transcended the generations and are still much loved in the present day.

The word, tonkatsu, in particular, is believed have derived from “pork katsuretsu,” from the French “côtelette” and English “cutlet.” Incidentally, pork katsuretsu was first invented by Renga-tei in Ginza. It first appeared on the menu in 1899, and the way in which it was served, with finely shredded cabbage and Worcestershire sauce, quickly attracted people’s attention.

(Photo provided by: Renga-tei)

Behind the scenes of the development of this popular dish, however, was much trial and error made by the first owner of Renga-tei. Renga-tei, which started out as a French restaurant, apparently served “veal côtelette”, but it was not well received by Japanese patrons, with diners complaining that it was too rich and caused heartburn. The owner responded to these criticisms with various ideas, such as using pork instead of beef, replacing the powdered cheese in the coating with egg, and deep-frying the pork in plenty of oil, using tempura as a reference.

The dish was initially served with bread, but responding to patrons’ requests, he created a style in which rice was served as a side on a bread plate.