Rice-paddy farming came to Japan approximately 3,000 years ago.

The technique travelled from southern China, crossing the Korean

Strait via the south of the Korean Peninsula, and was first established

in northern Kyushu. Before the arrival of rice-paddy farming, people

in Japan

depended on naturally-available sources of sustenance.

They would catch fish and shellfish, hunt animals, gather nuts,

fruits, berries, and grass roots, and use these for food.

The cultivation of beans took place to an extent, but essentially,

the Japanese people depended on the favor of nature.

Paddy-farming began amid an existing hunter-gatherer lifestyle.People cleared forests, built canals, and started to grow rice in paddies. The paddies allowed people to produce food themselves, without the need to rely on what was naturally available, bringing about a major change to their lives.

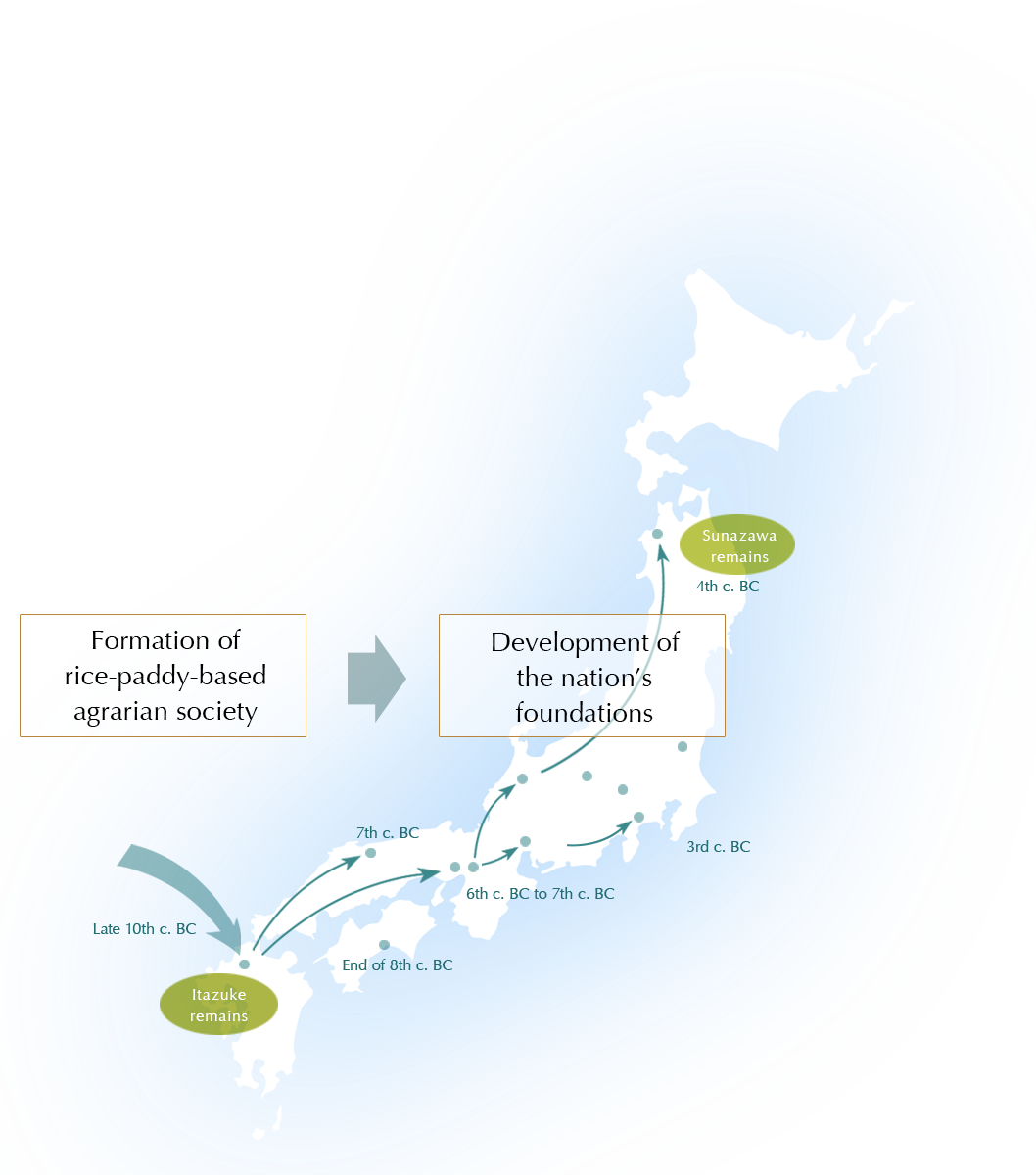

The Itazuke remains in the Hakata ward of Fukuoka are the site of one of the oldest farming villages where rice-paddy farming took place in Japan. Rice-paddy farming first took place here in the 10th century BC. The construction a hundred years later of earthen walls and a dry moat around the settlement suggests that a communal society focused on agriculture had been established at the site.

Having started in northern Kyushu, Japanese rice-paddy farming made its way to the northern edge of Honshu over the course of approximately 600 years. As the technique spread, cooperative agrarian societies based on rice-farming developed over hundreds of years across Japan.

It is likely that rice-paddy farming came to northern Kyushu through people who had rice seeds, farming tools, and knowledge of rice-farming techniques.

It takes a variety of farming tools to break ground and construct levees, and to irrigate the rice paddies in order to create the muddy soil required. These photographs show farming tools that were used until the start of the 20th century. Ignoring the iron cutting edge, you can see that the shapes of the hoes and plows have hardly changed from the Yayoi period to the current day. As the tools for working the soil have not changed significantly, one can infer that our ancestors carried out the same form of rice-paddy cultivation for three thousand years without any major changes to their techniques.

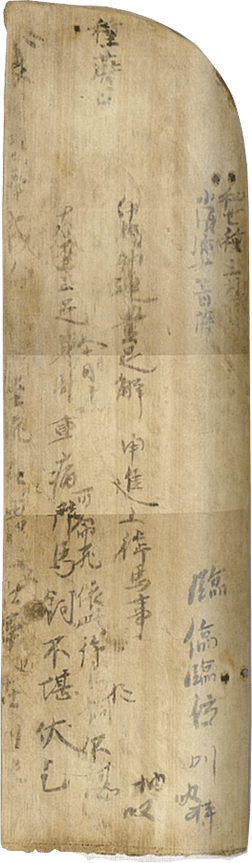

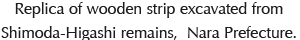

The rice that came with the paddy cultivation technique was selectively bred to suit the natural features of each region. Wooden strips that named seeds, indicating the types of rice that were cultivated at the start of the 9th century, have been excavated from remains in the different regions. Some strips that were discovered in remains located in Nara Prefecture have the days when various types of seeds were sown recorded on them. One can see from this that our ancestors made efforts to selectively breed rice in the different regions, in search of a bountiful harvest.

Above:Left: 9th-century wooden strip excavated from the Shimoda-Higashi remains, Kashiba, Nara Prefecture. The bottom plate of a white cedar box was reused to record the different types of seeds. This record states that wase seeds were sown on the 6th day of the 3rd month, and kosurume seeds were sown on the 11th day of the 3rd month.

Below:Right: 9th-century wooden strips excavated from the Attame jōri division remains, Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. These strips were attached to rice bags to give the names of the types of seed contained within. The variety name mewase is written on 1, and kohōshiko is written on 2.

After the arrival of rice-paddy cultivation, people gathered together around rice paddies, cooperated, and formed settlements. From this point, ancient Japanese society was supported by agriculture based on rice cultivation. From the late 7th century, the Ritsuryo system of government came into being, and as the workings of a new nation were set in place, a law providing for the allotment of rice paddies by the state was enacted. With this came the burden of a rice levy called so, which was determined based on the paddies that were allotted. Additionally, a rice loan system called suiko was also developed, in which seeds would be loaned during the spring, and the loan repaid in the autumn with the harvested crop and 50% interest on the seeds. These methods integrated rice among the country’s financial resources.

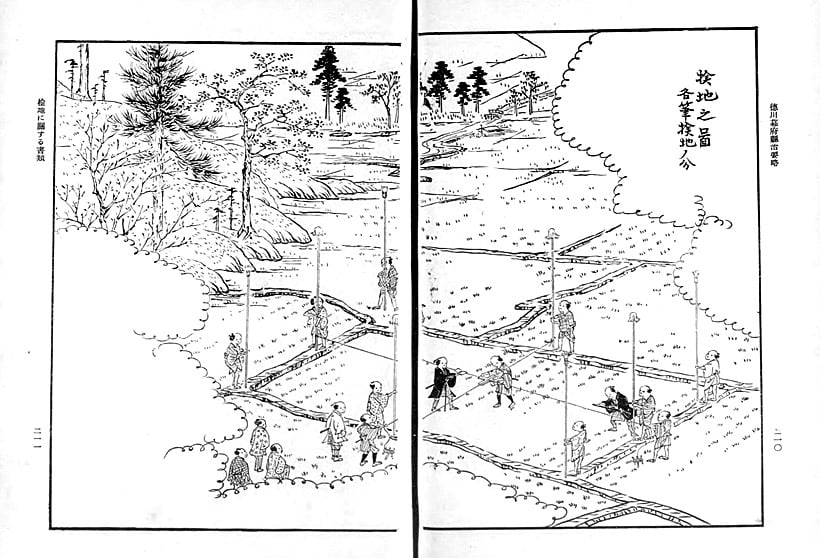

The system of using rice as an annual land tax and collecting annual rice taxes from around the country persisted through the medieval period until the Edo period. Medieval feudal lords would determine the size and area of paddy fields, responsible parties for land tax, and volumes of land tax together with villagers. The method of determining the land tax to be gathered from a territory was carried over into Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s land survey. Toyotomi created a system that obliged the bushi class to provide military service (for example, by sending soldiers in times of war) relative to the amount of land tax (rice yield) due in the territory that they controlled. The Tokugawa shogunate also carried on this system, which was used to control bushi such as the daimyo lords across the country. This is how rice was used from the medieval period to the Edo period for tax, and as a means of controlling the bushi, thereby supporting society.

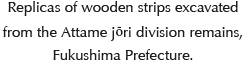

This is a land tax receipt sent from the Toji temple in Kyoto to the Noto Province in 1534, during the Sengoku period. The amount is given as ten million koku of rice, an impossible figure – this is a formality known as kissho. The document is in fact a fictional receipt intended to assert that the Toji temple was being well-managed, and to express in writing that the Noto Province was properly paying its land taxes. The first head priest of the Toji temple was the originator of such customary receipts.

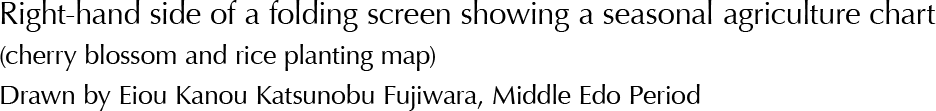

This is the right wing (depicting spring and summer) of a folding screen that depicts scenes of rice farming throughout the four seasons in the mid-to-late Edo period.

Our ancestors also felt a mysterious power in the rice that brought them a harvest every year. Across the country, people observe customs such as beiju (a celebration of one’s 88th birthday named for the similarity between the Chinese characters for “88” and “rice”) and the use of rice offered at temples in good-luck charms. These traditions are wishes for people to be healthy in emulation of the vitality of rice. Our ancestors also felt a mysterious power in the rice that brought them a harvest every year. Across the country, people observe customs such as beiju (a celebration of one’s 88th birthday named for the similarity between the Chinese characters for “88” and “rice”) and the use of rice offered at temples in good-luck charms. These traditions are wishes for people to be healthy in emulation of the vitality of rice.

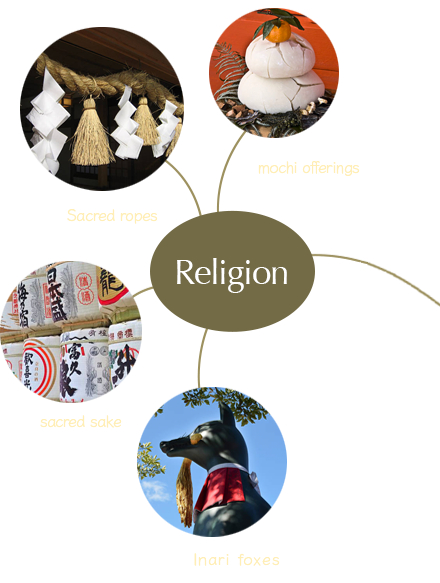

People prayed for good harvests at places where there were rice paddies. As if to demonstrate this, there are shrines all over the country dedicated to Inari, the kami of rice. Daikoku, one of the seven gods of good fortune, is also said to be the god of bumper crops.

People make offerings to the kami that bring them the bountiful harvests that sustain them, pray for abundant crops, and give thanks for the harvest they receive. One can say that the Japanese have continually repeated a history of prayer and thanksgiving amid this cycle of rice growth and harvesting.

Prayer for abundant crops takes place at the Ise Grand Shrine, which is said to have a history of roughly two thousand years. During the offering of the new year’s rice harvest in autumn, newly-harvested rice is offered to the kami, and thanks is given through prayer. At the Outer Shrine, daily sacred offerings in the mornings and evenings of rice and other foods have taken place for 1,500 years without fail. Rice simultaneously serves both as a foodstuff and as a special offering that connects people and kami.

Before eating, the Japanese customarily clap their hands and say “itadakimasu” – “I humbly receive.” This is a show of gratitude for not only the food that they receive then, but also toward all things related to the food that they will go on to receive. In Japan, there is a belief that there are kami in all things, and from a young age, people are taught not to waste a single grain of rice. The earnest prayer for bountiful crops demonstrates a wish for food to be abundant, and one can also get a glimpse of gratitude for the untiring efforts of our ancestors, who continued to farm rice so that they could continue to thrive.

Over its long history of cultivation, rice has deeply embedded itself in our lives not only as a foodstuff, but in other shapes and forms as well. Let’s take a look at the different forms of rice that are commonplace.

There are many ways to eat rice. For example,

in addition to plain, cooked white rice, there are

variations such as sushi, or the more portable

onigiri rice balls. All kinds of ways to eat rice

have been created: for example, sekihan is “red

rice” infused with the

color of adzuki beans,

and dishes such as zōsui and ochazuke involve

rice stewed in soup stock.

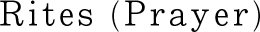

There are numerous processed foods and drinks that use

rice as an ingredient. Rice miso is made by fermenting soy

beans with rice koji (a special rice-derived mold culture

used for fermentation). Mochi rice cakes are made by

pounding steamed glutinous rice, and rice flour is used to

make wagashi, Japanese sweets. Sake is brewed using rice

koji, while mirin is a form of sake for cooking made from

glutinous rice.

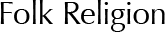

After harvesting the rice, the plants are dried, and the

resulting straw can then be woven to make sandals or

used to make the core of tatami mats. The straw can

also be woven into ropes or nets, and was used to

make straw rice bags.

Prayer for bountiful harvests led to

the offering of rice to the kami.

Mochi rice cakes and sacred sake are

offered at the new year and during

seasonal festivals, and sacred ropes

used at shrines are made from the

straw of rice plants. People

offered

up their harvest to show their

gratitude to the kami who blessed

them with rice.