The new Meiji government aggressively promoted the consumption of meat in order to help the Japanese build strong bodies, and by doing so, created a trend in which gyū-nabe, beef hotpot, became a symbol of civilization and enlightenment (see: "Meat Eating in Modern Japan").

It was amid this background that there was a movement to introduce Western knowledge and technologies in the field of meat processing. Let us look back on the achievements of the foreigners who came to Japan.

Illustration of animal slaughter by Westerners.

"Seiyo ryori tsu" ("The Western Cuisine Gourmet," 1872), an early Meiji-era book on Western cooking, describes various Western customs. This book was translated from the notes of the English people living in Yokohama and edited by the writer Robun Kanagaki. Collection of the National Diet Library

In 1874, William Curtis came to Japan from the United Kingdom and started production of the first ham to be produced in Japan, for foreigners living in the Yokohama settlement at Kawakami Village, Kamakura County, Kanagawa Prefecture (present-day Totsuka in Yokohama City). In addition to refining the production method, Curtis also worked hard to train craftsmen like Shuzo Tomioka, Mampei Saito, and Naozo Masuda and pass on his skills.

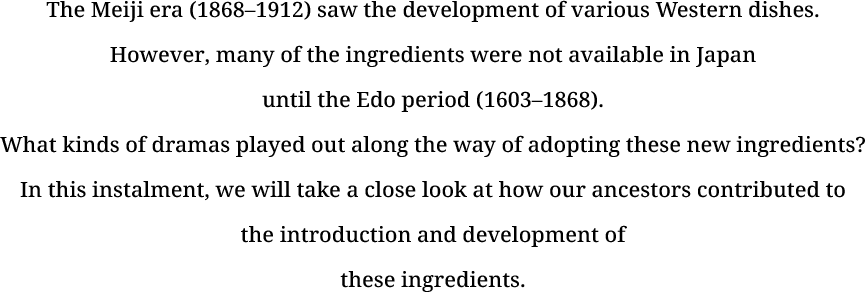

"Gaikokujin ryori no zu"

(“Illustration of Foreigner Cuisine," 1860): A scene of a kitchen in a foreign settlement at the end of the Edo period. The Westerner on the right can be seen cooking what looks like meat.

Collection of the National Diet Library

One of his disciples was Shuzo Tomioka, the founder of the Ofunaken food company, who released Japan's first ekiben (train bento) sandwich using imported ham in 1899, following the advice of Count Kiyotaka Kuroda, a politician of the time. Its flavor and rarity made it an immediate hot topic, but there was a problem: imported ham couldn't keep up with the sales.

Just as he was agonizing over how to deal with this situation, he found out about Curtis, who was producing ham nearby, and immediately became his pupil. In 1900, he established Kamakura Ham Tomioka Shokai (now Kamakura Ham Co., Ltd.), which was spun off from the ham production department of Ofunaken. Curtis eventually left Japan, but his traditional methods are still being followed by the Japanese.

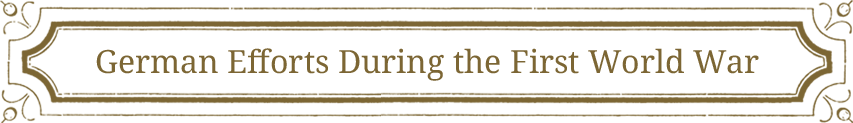

During the First World War (1914–18), several prisoner-of-war camps for German soldiers were set up in Japan, and it is said that as many as 4,500 prisoners were held there. At the Narashino camp in Chiba Prefecture, craftsmen including Karl Jahn, who was being held in Japan, started to produce sausages. In 1918, the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce took notice of the techniques demonstrated by Jahn and others, and sent Yoshifusa Iida, a member of the ministry's National Institute of Animal Industry in Chiba, to the camp to learn more. There, Iida learned about sausage production methods from Jahn and his fellows, and subsequently contributed to the spread and cultivation of German food-processing technology.

Photography courtesy of Kasumigaura City Museum of History

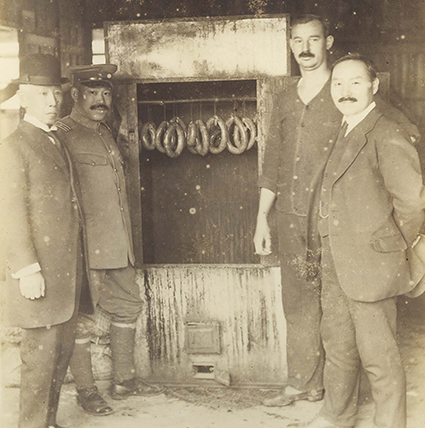

During this period, pork loin ham was also developed by August Lohmeyer, a German prisoner of war. Lohmeyer was originally a meister in the meat-processing industry, and after being brought to Japan, he worked in the kitchen of a POW camp in Kurume for five years. Even after being released, he did not return to Germany, and instead took a job at the Imperial Hotel. In 1921, he established a limited partnership company, Lohmeyer Sausage Manufacturing, and began doing business with the Imperial Hotel, the Seiyoken restaurant, the Mitsukoshi department store and others.

However, the Japanese livestock industry at the time was still immature, and ham made from pork leg was very expensive. Pork had yet to make significant inroads into Japan, though there was some demand in Chinese quarters such as the one in Yokohama, and consumption of loin and tenderloin was rare. Aiming to make use of pork without waste, Lohmeyer developed a rolled, boiled ham product ("rolled ham", later called "loin ham"). Boiled ham attracted attention because it was convenient and easy to immediately eat.

In 1925, Lohmeyer opened a German restaurant and shop in Ginza.The shop became popular among cultural figures, and was featured in various literary works.

Photograph courtesy of Lohmeyer Corporation

National Diet Library collection

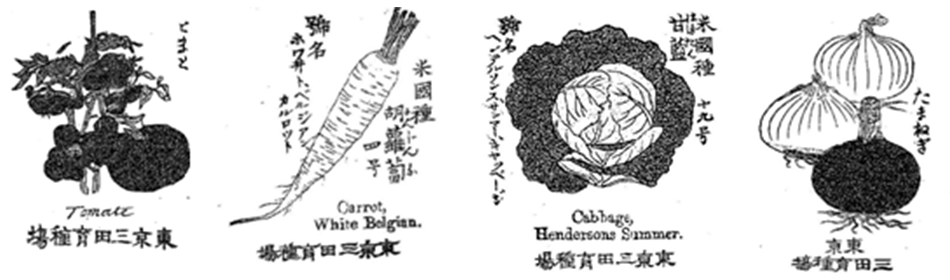

Many of the standard vegetables of today’s Japan were first grown in earnest in the Meiji era, during which time they became popular. Of these, tomatoes, carrots, cabbages, onions, and potatoes are commonly used as foodstuffs to this day, but in Japanese society until the end of the Edo period, tomatoes were regarded as an ornamental foodstuff, and potatoes were not eaten because they were seen as a food for livestock or as a relief crop (foodstuffs stored for famines).

Amid rising interest in integrating Western food during the Meiji era, the government came up with a variety of agricultural promotion measures similar to those for encouraging meat eating. In addition to establishments in Tokyo, such as the Naito Shinjuku Experimental Station, Komaba Agricultural School, and Mita Plant Breeding Institute, a frontier agricultural institute was established in Hokkaido to conduct research on the cultivation of Western fruits and to improve their varieties.

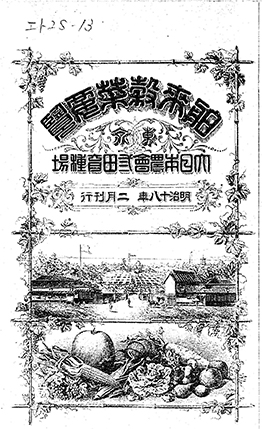

("Catalog of Imported Grains and Vegetables," 1885), with "Mita Plant Breeding Institute" written on the cover. Collection of the National Diet Library

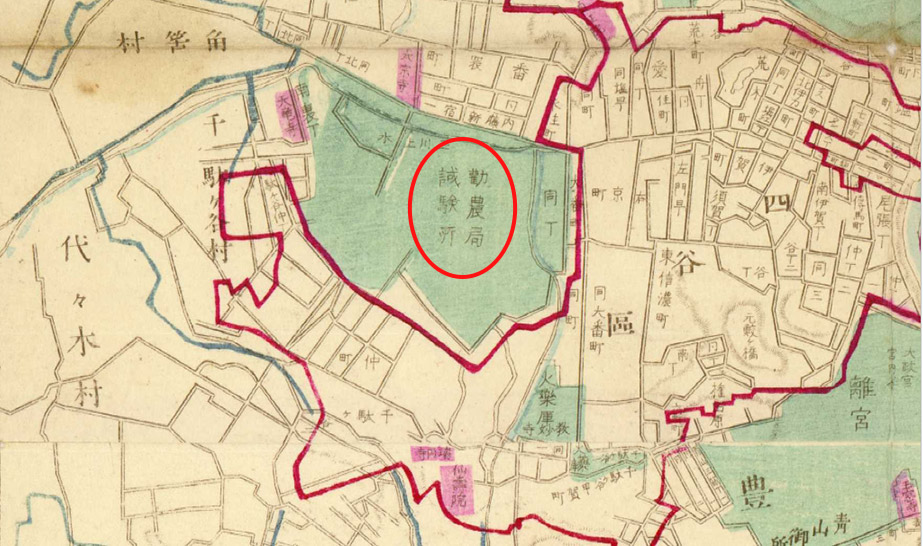

In 1872, the government acquired land from the Naito family (vassals of the Tokugawa family) and neighboring privately-held land to establish the Naito Shinjuku Experimental Station (now Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden), where it set out to promote modern agriculture in Japan. Various departments were established within the site, such as the Department of Livestock Production, the Department of Arboriculture, the Department of Sericulture Testing, the Department of Agricultural Tools, and the Department of Agricultural Science. These departments not only purchased seeds and seedlings from Western countries, but also studied the cultivation of plants obtained from various countries around the world, as well as pest control methods. They had success in importing and disseminating horticultural technology, and also built Japan's first greenhouse.

(The ellipse area in the center)The map of Tokio Japan(1879)

International Research Center for Japanese Studies collection

Hayato Fukuba, an agricultural scientist from Iwami Province (present-day Shimane Prefecture), was an apprentice at the Agricultural Promotion Bureau Experiment Station (The name was changed from Naitoshinjuku Agricultural Experiment Station,1877) where he practiced horticultural agriculture and produced processed foods. He went on to improve many kinds of vegetables and fruit trees, both native and Western, and actively shared his research results with his successors. It is said that vegetables and fruit grown in Shinjuku Gyoen at that time were used as ingredients in food served to the Imperial family. In 1900, Fukuba produced Japan’s first domestic variety of strawberries, which were named after him. Fukuba strawberries have later become a high-grade variety grown throughout Japan.

Furthermore, following on from his experience of attending court banquets and national events both in Japan and abroad, Fukuba was appointed to direct the banquet for the enthronement ceremony of Emperor Taisho, which was a resounding success. Together with Tokuzo Akiyama, known as "the Emperor's cook," Fukuba had the honor of presiding over the largest banquet in Japanese history.

Photograph courtesy of Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden, Management Office

After the opening of Japan to the world, Japan embarked on modernization centered on policies to "enrich the country and strengthen the army" (fukoku kyohei) and encouragement of new industries (shokusan kogyo) in order to narrow the gap between Japan and the allied Western powers. Particular importance was attached to improving the physique of the Japanese people, and subsequently, the practice of eating meat and the consumption of dairy products, in line with the eating habits of Westerners, attracted attention. However, dairy was more difficult to promote than eating meet, as milk had the strong cultural perception as being something that only calves would drink.

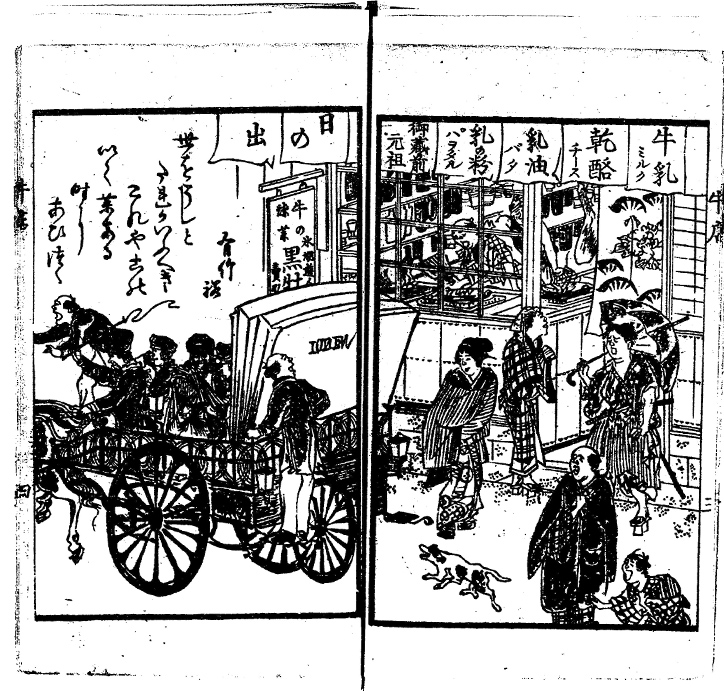

In order to alleviate national dislike of these novel foodstuffs, the new Meiji government attempted advertising and educational campaigns to aid their integration into Japanese society. In 1869, the Gyuba Company, a national policy concern, was established in Tsukiji, Tokyo to sell beef and milk. The following year, the Gyuba Company published "Nikushoku no setsu" ("On Eating Meat"), an essay written by Yukichi Fukuzawa in praise of both meat and milk. The paper extolled the medicinal effects of milk, describing it as a panacea for all kinds of diseases, a font of eternal youth and longevity, and an aid to the mind’s workings, and it played a part in alleviating the Japanese people’s anxiety about dairy products.

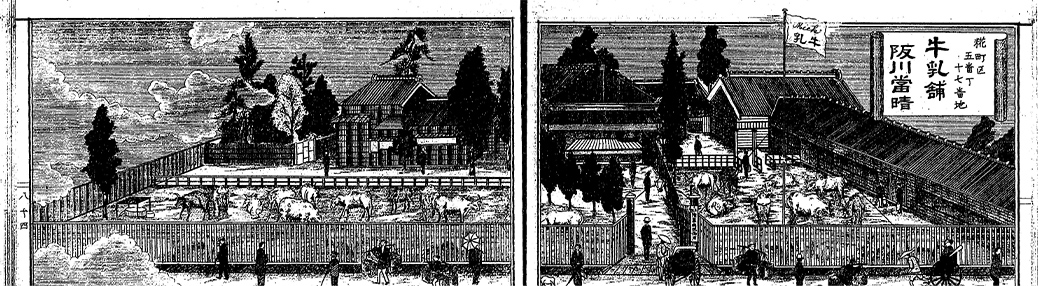

Additionally, "Tokyo shoko hakuran e" ("Illustrated Views of Trade and Industry in Tokyo", 1885), a depiction of influential commercial and industrial businesses in Tokyo, lists as many as 14 milk dealers, all of which had prestigious premises.

Furthermore, from the beginning of the Meiji era, translations of Western medical text introduced the significance of dairy products in child rearing, and touted nursing methods using cow’s milk. These nursing methods substituting cow’s milk for mother’s milk were referred to with names like "the artificial nurture method," "the artificial child-rearing method," "the

artificial nourishment method," and so on, and were discussed in parenting and housekeeping books.

By the Taisho era (1912–26), milk began to be viewed not only as a substitute for breast milk, but also as an everyday ingredient, and home cooking using milk began to emerge. Furthermore, due in part to the influence of modern nutritional science, the idea that drinking milk improves the physique was strengthened, and the movement to recommend drinking milk during

early childhood became particularly active.

Setagaya Ward Folk Museum collection

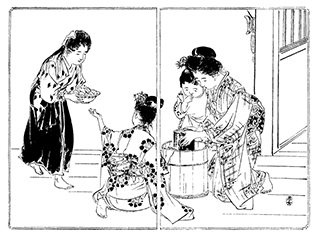

by Gensai Murai (published in 1903)

(Pleasures of the Table: Autumn) describes making ice cream at home.

In 1865, the first Japanese ice cream business was born in a settlement in Yokohama. When Richard Risley Carlisle, an American, started selling Tianjin ice imported from China instead of the expensive Boston ice, so too did Japan’s ice cream parlors get their start.

In 1869, Fusazo Machida opened an ice cream shop on Yokohama’s major Bashamichi street, becoming the first Japanese person to manufacture and sell ice cream. However, at the time of its opening, it was only a rare stop for foreigners, and the Japanese found it very unapproachable.

In fact, during the early Meiji era, ice cream was still a luxury item and not something that ordinary people had ready access to. It is also said that the invention of the hand-cranked ice cream maker in the United States was the catalyst for its widespread use in ordinary households. These ice cream makers were easy to use: ice and salt are put into a wooden tub, ingredients such as milk, egg and sugar are put into a middle cylinder, and the ice cream is made by stirring using the hand-crank. By the end of the Meiji era, hand-cranked ice cream makers were being imported to Japan and gradually became popular in Japanese households. Cookbooks from that time also described how to make simple ice cream by stirring it manually using tin cans and wooden tubs at home. Ice cream must have attracted attention as part of a longing for Western lifestyles.