Though the Meiji era (late 1868 to mid-1912) saw high receptiveness to Western culture, family meals did not change substantially; meals that consisted of rice, a soup, and side dishes of vegetables and fish remained the standard.

However, with the passage of time, Western cuisine in Japan gradually changed into a style that suited the national palate as Japanese and Western culture merged. Eventually, Japanese-style Western cuisine gained its Japanese citizenship, becoming known as yōshoku (“Western food”) and securing its place as a side dish on the family dinner table.

As the country entered the Taisho era (mid-1912 to the end of 1926), an increasing number of articles and other writings about yōshoku in home cooking appeared in cooking books and women’s magazines, and recipes that tailored yōshoku to suit the flavor of rice filled the pages. It was during this period that the three big names in yōshoku came to the fore: cutlets, “rice curry”, and croquettes.

With the transition into the Showa era (1926–1989), Westernization took even greater strides mainly in city life. Department stores filled their shelves with imports from Europe and the Americas, such as Western alcoholic drinks, and more and more restaurants serving yōshoku emerged. The department stores offered shoppers a taste of modern culinary culture, and they became a popular destination for entire families to visit, which contributed greatly to the adoption of yōshoku.

Gendai Shōgyō Shashinchō (“Photograph Album of Modern Commerce”) (1936)

– Collection of the National Diet Library

Tōkyō Shashinchō (“THE VIEWS OF GREAT TOKYO”) (1932)

– Collection of the National Diet Library

Photograph courtesy of Nichirei Foods Inc.

In the period of rapid economic growth after the Second World War, major changes began to occur in dietary lifestyles at home, with instant meals, retort-pouch foods, frozen food, and other processed foods going on sale, along with the prevalence of electric appliances including rice cookers and refrigerators. A wide menu of easily prepared yōshoku that can be simply heated up, like retort-pouch curry, or frozen croquettes or hamburger steaks, took its place on the daily dinner table.

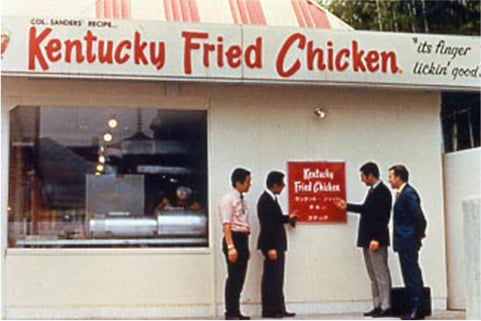

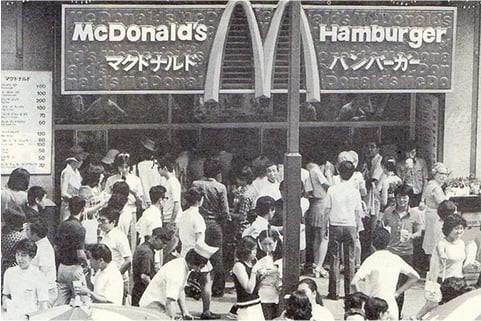

Later, international events like the Tokyo Olympics of 1964 and Expo’70 paved the way for even further internationalization of food in Japan. In particular, the fast food exhibited at Expo’70 drew close attention, and it was around that time that hamburgers, fried chicken, and other fast-food staples became a part of Japanese dietary lifestyles.

Photograph courtesy of Kentucky Fried Chicken Japan Ltd.

Photograph courtesy of Japan Archives

The 1980s were called “the age of 100 million gourmets”, and during this time cooks actively went abroad for training, with restaurants serving authentic French cuisine, Italian cuisine, and so on springing up after their return. Alongside this trend, consumption of cheese and wine (essentials of Western cuisine) shot up, marking the significant progress of Westernization of dietary lifestyles.

Post-war changes in living environments also greatly affected the Japanese dining table. To remedy the lack of places to live after the war, the decade following the mid-1950s saw the birth of 2DK (two rooms plus a dining room and kitchen) housing complexes, which were based on a separation of eating and sleeping areas. Together with the adoption of Western lifestyle formats, the short-legged chabudai tables used for Japanese meals were abandoned and replaced with the Western style of eating while seated around a dinner table. The kitchen would be situated right next to the dining table, fitted with plumbing and gas, triggering the wide spread of another feature of Western lifestyles—chatting with the family while preparing the meal.

At the same time, kitchen appliances like electric rice cookers, refrigerators, toasters, and microwaves progressed through their development as well. The appearance of these appliances not only alleviated the burden of preparing meals; they also brought about an expansion of the repertoire of Western foods served for guests, on larger plates than traditional Japanese tableware.

Radio cooking programs first appeared on Japanese airwaves in 1925. Learning from actual human voices on the radio must have been a revolutionary experience for the women of the time, who until then had been learning new information from media such as cooking books and magazines.

After the war, however, the style shifted from learning from the radio to learning from television. Cooking television programs through which viewers could actually see the steps of the recipe provided the same kind of fun and novelty as entertainment programs, and they quickly enchanted the housewives who were enthusiastic about Western cuisine.

The first of the cooking television programs is thought to be Okusama Oryōri Memo (“Cooking Notes for Married Women”, Nippon Television), which aired in 1956 and at times commanded a viewership rate of over 30%.

In 1957, the longest-running program, Kyō no Ryōri (“Today’s Cooking”, NHK), began its run, which continues to this day. This program made sure that viewers could reproduce the meals at home, and it gained a lot of attention for the way it showed how much seasoning to use and how to carry out the steps of the recipe in an easy-to-understand manner. The dish shown in the first broadcast, incidentally, was curry rice with oysters. In the month after the program started airing, stew and macaroni gratin followed, making the interest in yōshoku dishes clear. Additionally, in the year after broadcast started, a textbook was printed to help viewers cook the recipes at home. This method of learning from television achieved results with how easy it was to understand, and it went on to become a standard for teaching cooking.

May 1958 volume,

NHK Publishing, Cover picture, Kiyoshi Saito

There was also a rich variety of instructors on hand to teach the knack for authentic Western cooking, from top chefs like Nobuo Murakami (Imperial Hotel), one of the chief chefs of the Tokyo Olympic village restaurant, and Masakichi Ono (Hotel Okura), a master of French cuisine, to other cooking experts who were well-versed in cuisine from around the world.

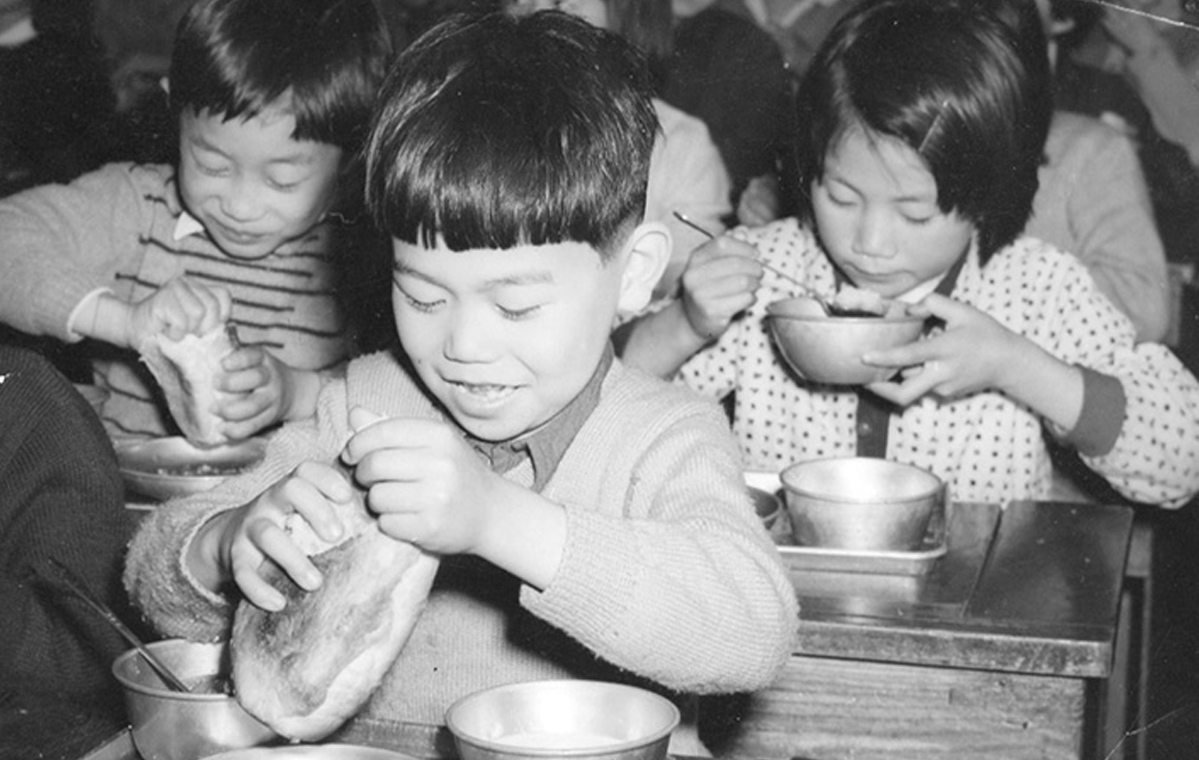

After the war, Japanese schools resumed providing school lunches to children in order to improve their nutrition. Aside from bread and milk, they also made efforts to provide Western-styled side dishes, and this went on to significantly influence the Japanese palate.

Measures to provide food at school began in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture. It is said that in 1889, at Chuai Primary School, a school on the grounds of the Daitokuji temple, a free school lunch was provided for the first time in Japan, targeting impoverished children who had difficult lives and did not have access to full meals otherwise. The menu was a simple one: salted onigiri, dried fish, and pickled vegetables. Based on this history, on some days schools in Tsuruoka City provide onigiri just like the ones from back then, even now.

After the introduction of free meals in Tsuruoka, the practice spread across Japan under the banner of aiding impoverished children, but it was not entirely introduced on a national level. Time continued on, and in the wake of the Manchurian Incident and the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan plunged into the Second World War. The focus shifted to transporting goods to the front, meaning people at the home front faced the difficult problem of food shortages, and by 1940, school lunches had finally stopped.

(onigiri, salted salmon,

pickled vegetables)

(goshiki [”five-color”] rice,

nourishing miso soup)

(powdered skimmed milk, tomato stew)

After the war, discussions took place about resuming school lunches for children, in order to improve the state of children’s nutrition that was further worsened by the difficult food situation.

In 1946, the then-Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry issued a vice-ministerial notice “Encouragement for the spread of the practice of providing school lunches”, establishing the school lunch policy. Pioneering this new policy, the first school lunches after the war were provided at Nagatacho National School in Tokyo, and by the following year, school lunches were being provided to roughly 3 million children across Japan’s cities.

Additionally, it was the United States and UNICEF that provided aid in the form of the powdered skimmed milk, butter, jam, canned foods (ham, sausage, etc.), flour, and other foodstuffs used for Japanese school lunches after the war. Through these events, bread and powdered skimmed milk (later, normal milk) became standard features of school lunches.

Furthermore, school lunches also incorporated numerous yōshoku dishes to supplement animal proteins and fat that were lacking from children’s diets, including fried whale meat, curry stew, fried fish, and gratins. This experience of school lunches joined the backdrop of factors behind the increasing number of children who enjoyed eating yōshoku.

(bread roll,

milk (powdered skimmed milk),

fried whale meat,

shredded cabbage, jam)

(spaghetti with meaty sauce, milk, French salad, pudding)

(curry rice, milk, salted vegetables, fruit (banana), soup)

All photographs courtesy of Japan Sport Council

The modernization that took place after the Meiji era caused an explosive growth in urban populations. Alongside this, more and more families started eating out on a regular basis, and department stores and diners aimed at the general public serving yōshoku began to appear.

Additionally, the post-war period of high economic growth introduced new business formats such as family restaurants and fast-food restaurants backed by foreign capital, accelerating the spread of accessible, reasonably priced yōshoku.

During the period from the Meiji era to the Taisho era, department stores entered the restaurant business and started serving stylish yōshoku offerings. However, the yōshoku available at the time was a prize beyond the reach of ordinary people. It was far from a casual meal, in fact.

However, on entering the Showa era, the habit of enjoying yōshoku with the family became increasingly prominent. In 1930, okosama lunch, children’s lunch with a variety of yōshoku side dishes, was created at the initiative of Taro Ando, the chief manager of the Nihombashi Mitsukoshi restaurant. By 1932, okosama lunch was joined by chicken rice, hayashi rice, bread, ice cream, hot chocolate, fruits, and other foods aimed at children, showing how families had adopted the habit of having yōshoku together.

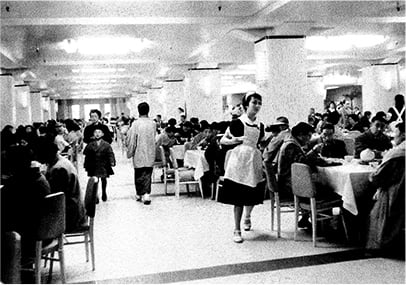

As Japan overcame the post-war recession, department stores expanded not only in large cities like Tokyo and Osaka, but also to the regions. Taking the family to a department store on a day off and having a meal together at the restaurant was one of the joys of life in the Showa era.

What made department store restaurants so attractive more than anything else was the diverse selection of dishes. In addition to yōshoku and Japanese food, there was everything from Chinese food to all kinds of desserts, with a cross-generation appeal that made the restaurants ideal for quality time with the family.

Photographs courtesy of Isetan Mitsukoshi Ltd.

Meanwhile, the appearance of more simple diners on street corners gave further momentum to the spread of yōshoku. Among these was Sudachō Shokudō, which opened in Tokyo’s Kanda area in 1924 with a sign offering “simple yōshoku”. The restaurant served curry rice, cutlets, and other yōshoku at a much lower price than department store restaurants, and it was successful enough to grow into a chain of restaurants in later years. It is likely that the rise of these casual diners also further reinforced the spread of yōshoku.

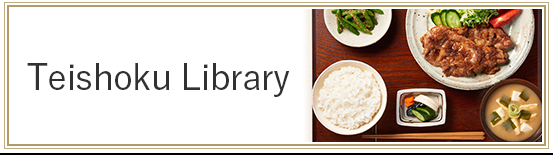

During the 1970s, American-style family restaurants took off. Royal, who had a successful restaurant at Expo’70 in Osaka, opened Royal Host in 1971, and this was followed by other chain restaurants opening one after another, such as Denny’s (1974) and Joyful (1979). The number of restaurants continued to grow nationwide, cementing the position of family restaurants as a new place for families to relax.

The main appeal of Japanese family restaurants is that not only do they serve yōshoku like hamburgers, spaghetti, and steaks, but they also use Japanese-style sauces and serve dishes in a teishoku (set meal) style. It seems these restaurants were successful in capturing the hearts of many Japanese people by offering dishes that they had an emotional attachment to, even though the food was of Western origin.

The Showa era was followed by Heisei (1989–2019) and now Reiwa (2019–), during which time the internationalization of food has only continued to progress, and today, one can enjoy dishes and sweets from countries all over the world in Japan. At imported food shops, supermarkets, and other stores, one can obtain a variety of foreign ingredient and seasonings, and, through the internet or other forms of media, easily learn how to use them or find recipes that take advantage of them. We truly do live in an era where one can enjoy the food cultures of the world right in Japan, without having to embark on a plane flight abroad.

However, becoming absorbed in foreign food culture to the point of letting one’s interest in use of domestic ingredients wane, or allowing one’s understanding of traditional seasonings to fade, would be failing to recognize the true importance of these things. In fact, with the diversification of everyday diets, the Japanese are accelerating their move away from a rice-based diet, and the increase in lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension associated with Westernized diets has become an important issue that we cannot overlook.

As a result of these circumstances, recent years have seen more and more studies conducted to take another look at the health value of traditional Japanese cuisine, which has an excellent nutritional balance. Today, Japanese cuisine attracts strong attention from all over the world. Yōshoku certainly is a kind of Japanese food culture, having developed and become established since the Meiji era, but it is important to keep in mind how one incorporates it into one’s daily diet, while skillfully combining it with traditional Japanese cuisine styles—the accumulation of the wisdom of our predecessors.

Yōshoku would never have become quite so universally popular without the spread of Western-style seasonings and condiments developed for home use. In the early days, the most commonly used products were imported, which limited them to Western-cuisine restaurants and upper-class households, but with the start of domestic production in the 20th century, it became possible for ordinary households to gain access to these ingredients.

Tomato Ketchup

Ichitaro Kanie (founder of the current Kagome Co., Ltd.) had cultivated tomatoes and other Western vegetables in Tokai City, Aichi, and in 1908, he began development and subsequent manufacturing of tomato ketchup. Still, one could say that it was a continuous process of trial and error to develop a condiment that used tomatoes, a vegetable that the Japanese were simply unfamiliar with. However, his efforts paid off: today, tomato ketchup is an essential part of yōshoku classics like omelet rice, chicken rice, spaghetti Napolitan, and other greats.

Photography courtesy of Kagome Co., Ltd.

Mayonnaise

The first Japanese mayonnaise was sold by Food Industrial Corporation (now Kewpie Corporation) in 1925. It was given a charming name to endear it to the public: Kewpie Mayonnaise. This brand came with an equally charming mascot character.

The commercialization of mayonnaise gave yōshoku dishes like potato salad and macaroni salad (which are still popular today) an opportunity to join the ranks of homemade food.

Photograph courtesy of Kewpie Corporation

Salad Oil

In 1924, Nisshin Soybean Crushing Co. (now Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd.) released Nisshin Salad Oil, a type of vegetable oil. The name “salad oil” came from its ability to be used as-is for preparing salads and so on—this oil does not harden when cooled. At the time, oil was mainly used for deep-fried foods, but the arrival of salad oil made it possible to make mayonnaise and dressings at home, further aiding the Westernization of the dining table.

Photograph courtesy of Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd.