From the period that rice-growing was brought to Japan approximately 3,000 years ago, right up to the present day, our ancestors toiled to find a way to grow a large amount of rice on narrow terrain.

Japan is described in the Kojiki, a record of the country’s development into a nation, as the “Country of Lush Reed Plains,” a reference to the bountiful growth of rice and an indication of how rice has symbolized Japan since ancient times.

In this corner, we will introduce you to Toyama’s diverse rice culture through its history, culture, and beautiful natural scenery.

“View of Okayama Castle from Korakuen” (Okayama City) © Okayama Prefectural Tourism Federation Held to be one of Japan’s three greatest gardens, Korakuen is a circuit-style garden built by Nagatada Tsuda under the orders of feudal lord Tsunamasa Ikeda. It is said that the land reclamation works that were underway at the time were suspended to allow construction of the garden to proceed. The task took approximately three years, seeing initial completion in the year 1700.

Okayama Prefecture has almost a rectangular shape, with the Chugoku Mountains, which rise over 1,200 meters above sea level, spanning east-west on the northern end of the prefecture. From there, the terrain slopes gently to the south, forming plateaus and basins, expanding into the Okayama Plain and reaching the Seto Inland Sea. The three main rivers, the Yoshii, Asahi, and Takahashi, originate in the Chugoku Mountains, and form small valleys in the hills as they gently flow through the plains into the Seto Inland Sea.

Okayama Prefecture is called “a land of sun”, and this comes from the fact that there is little rainfall there—about 1,000–1,300 millimeters annually on the plains by the inland sea. (The national average is 1,600–1,800 millimeters per year.) However, the average rises the closer one gets to the Chugoku Mountains, where it reaches up to 2,000 millimeters, and during the winter, it is said that the mountains are “blanketed by a hundred days of snow”.

The Sanyo Route of the southern side of western Honshu connects Kyoto & Nara, once the center of politics in ancient times, and Dazaifu & Nanotsu (now Hakata Port), which served as the gateway to East Asia. The area also had military value as a land and sea transit point enabling access to the San’in region (the north side of western Honshu). Sanyo and the Seto Inland Sea route were the main logistics arteries, and there was a great deal of exchange between north and south through the Izumo Highway and the three major rivers, with port towns such as Shimonotsu and Ushimado thriving with traffic.

The foundations of the textile industry originated with commercial crops such as cotton and rush, which were actively cultivated during the Edo period (1603–1867), and this led to the development of post-war industrialization. In the modern era, a railway network connects each end of the prefecture, and features such as the coastal industrial area make Okayama a place that represents the Seto Inland Sea region.

The old Kibi Province was a birthplace of ancient Japanese culture alongside the Yamato region, and it was a powerful nation that left behind feats such as the ancient Tsukuriyama burial mound, the fourth largest in Japan. From around the 4th century, Kibi gradually came under the influence of the Yamato government, and in the 7th century, it was divided into the provinces of Bizen, Bitchu, and Bingo (“Near Kibi”, “Central Kibi”, and “Far Kibi”, from the perspective of the capital region). At the start of the 8th century, Bizen was further divided to create the province of Mimasaka.

The main shrine building, a national treasure and an example of hiyoku irimoya-zukuri (building with paired wing hip-and-gable roof) architecture, was built in 1425 by Yoshimitsu Ashikaga. There, Kibitsuhiko-no-Mikoto, who was dispatched to the Sanyo Route during the reign of Emperor Sujin and ruled the area, is enshrined.

Right:“Earthenware Coffin” (Yagami Burial Mound, Akaiwa City)

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Ancient Kibi Cultural Properties Center Above:“Weight-shaped Earthenware” (Kamo Madokoro Ruins, Okayama City)

Below:“Earthenware Coffin” (Yagami Burial Mound, Akaiwa City)

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Ancient Kibi Cultural Properties Center

The uniquely shaped ritual implements and coffins tell the story of the region’s unique culture.

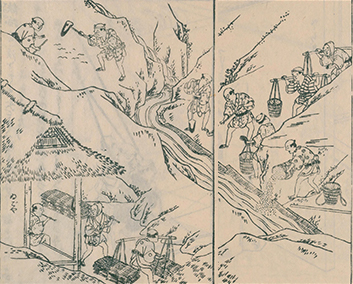

Rice cultivation came to northern Kyushu approximately 3,000 years ago, and reached the Seto Inland Sea area approximately 300 to 400 years later. During the early Yayoi period, the paddy fields at the Tsushima site used the natural topography as it was. Taking advantage of the slight incline of the terrain, the paddies were intricately divided by ridges to

efficiently fill them with water. The individual plots were elongated, reflecting the slope of the terrain, and they did not have a uniform area; some were only a few square meters, while others were up to 70 square meters.

However, the late Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD) paddy fields found at the Hyakken River Haraojima site consist of a series of uniform, square-like plots, which were also expanded by excavating a slightly higher shelf. It is thought that this difference originates from an increase in demand for rice due to population growth, as well as the spread of iron tools

that enabled large-scale working of the land. Having acquired new rice cultivation and civil engineering techniques, people gradually transformed the plains into more and more paddy fields with the aim of increasing rice production.

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Ancient Kibi Cultural Properties Center Above:“Tsushima Ruins” (Okayama City)

Below:“Hyakken River Haraojima Ruins” (Okayama City)

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Ancient Kibi Cultural Properties Center

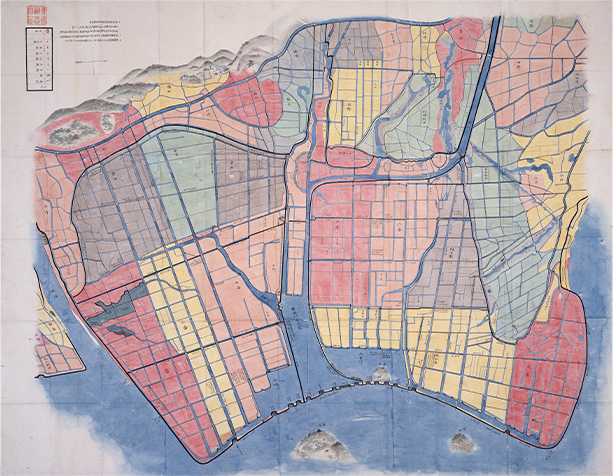

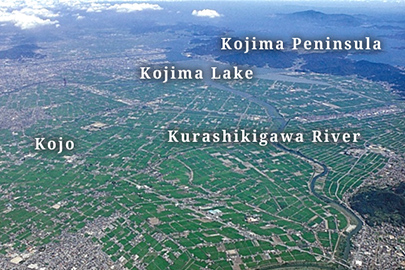

The ancient Kojima Bay was a vast inland sea called “Kibi no Anaumi”, and what is called Kojima Peninsula today was an island at the time. The place once occupied by the inland sea gradually became a tideland due to the accumulation of sediment carried by the rivers, as well as the large tidal range of the Seto Inland Sea. The earth and sand runoff from tatara steelmaking (which began around the 6th century) filled in the land, and it is said that by the time of the Sengoku period (1467–1615), one could walk across the former sea.

During the Edo period, development of new rice fields in Kojima Bay progressed, transforming the shore into usable land, but even during the early Edo period, the scale of new rice field development was about 4-50 hectares. By the latter half of the 17th century, the population of the territory increased, leading the feudal domain to start the development of

new, large-scale rice fields in order to ensure financial stability by increasing revenue from the annual rice tax.

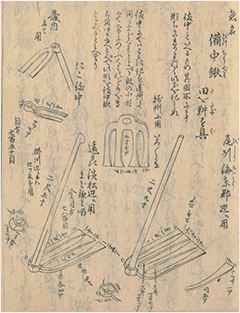

Proper drainage is important to develop a new rice field on reclaimed land. Entrusted with the development of the new rice fields, Nagatada Tsuda developed a new method of dividing off the flood-inhibiting pond at the mouth of the river with a sluice gate, which retained the water from upstream and could drain water at low tide by opening the gate. This led to

the successful completion of the new rice fields at Kōjima (about 560 hectares) in 1685. In 1692, the new rice fields at Oki (about 1920 hectares) were completed, greatly contributing to the domain’s coffers.

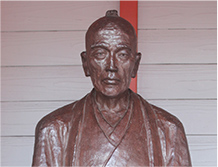

The domain lord Mitsumasa Ikeda praised Nagatada Tsuda, declaring that no man in the land could match his abilities. Aside from developing new rice fields, Tsuda also built the Korakuen garden and the Shizutani School, carried out civil engineering projects to excavate the Kurayasu and Hyakken rivers, and developed the port at Ushimado—achievements that remain to this day.

(Nagatada Tsuda, b. 1640–d. 1707)

Later, land reclamation works in the Okayama Domain stalled until the first half of the 18th century, but the debate resurfaced in 1879 through a petition by former samurai, who had lost their jobs and status. A land reclamation project subsequently began in 1899, financially supported by the wealthy Osaka merchant Denzaburo Fujita and led by the Dutch engineer Anthonie Rouwenhorst Mulder, and was completed in 1957. Of the 5,676 hectares reclaimed, 4,263 were used to develop paddy fields.

In 1950, the Kojima Bay Freshwater Lake Project was started to secure water for this vast area. By 1962, Kojima Bay was cut off by a 1,558-meter embankment, creating Lake Kojima, a huge freshwater lake of 1,088 hectares.

Below: “Agricultural land around Lake Kojima created by reclamation” Photograph courtesy of Okayama Prefecture

Right:“Tractors Introduced for Kojima Bay Land Reclamation in the Early Showa Era”

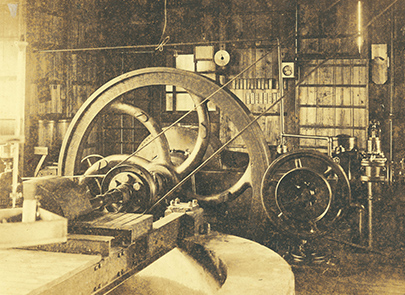

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Koyo High School Above:“Oil-engine Water Pump (Taisho Era)”

Below:“Tractors Introduced for Kojima Bay Land Reclamation in the Early Showa Era”

Photographs courtesy of Okayama Prefectural Koyo High School Kojo Village, which was developed from the close of the Edo period through to the Meiji era (1868–1912), was at the forefront of pre-war mechanized agriculture. Animal-powered water pumps were introduced during the Taisho era (1912–1926), and from 1924, oil engines began to mechanize the work. By 1939, 15% (423 units) of all the cultivators in Japan were in operation here. Okayama led Japanese agriculture with mechanization not seen elsewhere in the nation, becoming a mecca for production of agricultural equipment.

© Okayama Prefectural Tourism Federation

Above:“Kitasho Terraced Rice Fields”

Below:“Ohaganishi Terraced Rice Fields”

© Okayama Prefectural Tourism Federation The Kibi highlands is home to many terraced rice fields, tanada, and the total area of these is the second largest in Japan. Some are over a thousand years old, and there are also many reservoirs created for irrigation.

Column: Kibi-dango

Okayama Prefecture is famous for the tale of Momotaro. The underlying story is about how a demon (or in this case, a foreign tyrant) called Prince Ura of Baekje, or sometimes Kibi no Kaja, was defeated by Kibitsuhiko-no-Mikoto, son of Emperor Korei and one of the four generals who brought Kibi Province under Yamato rule. The rations Momotaro carried with him, hung at his waist, consisted of kibi-dango, or millet dumplings.

Fox-tail millet, common millet, buckwheat, and other various grains have long been produced in the mountainous (highland) areas of Okayama. It seems kibi-dango have been famous since ancient times, and old literature makes a reference to “the best kibi-dango in Japan” (Inryoken Nichiroku “Inryoken Diary”, 1492). Later, Koeido (established in 1856) started large-scale sales of kibi-dango, becoming famous nationwide.

From the coastline to the mountains, the dietary culture of various regions flourishes in Okayama. The plains are relatively temperate, and the Seto Inland Sea provides a bounty of seafood. In the snowy north, “blanketed by a hundred days of snow”, one cannot produce off-season crops in rice paddies, and so by the mid-Showa era (1926–1989), slash-and-burn agriculture was carried out to cultivate millet, buckwheat, adzuki beans, rapeseed, and konjac. Wild mountain plants, mushrooms, and bamboo shoots were also often eaten. Terraced rice fields and reservoirs were built long ago in the hills of the Kibi highlands, and wheat, sweet potatoes, millet, corn, buckwheat, and so on were also cultivated and served as staples. In the southern plains, people ate barley rice made using the secondary crop of the rice-producing regions, and it seems that sweet potatoes were the next most common food staple.

Left:“Wheat Dumpling Soup” (Kibi highland region)

Right:“Summer Dinner” (southern plains/hilly region)

Above:“Wheat Dumpling Soup” (Kibi highland region)

Below:“Summer Dinner” (southern plains/hilly region)

Flour-based foods like dumplings and noodles were also common.

“Bamboo Shoots Simmered in Rice Bran” (mountainous region)

This dish consists of the shoots of a type of bamboo with bow-shaped roots simmered in rice bran and miso. This is often eaten during the rice planting season.

“Yakkome” from the Chugoku Mountains region

This dish uses aogome (“green rice”), which is easy to grow in paddy fields in cold regions. The unhulled rice is soaked in water for a whole day and night, then roasted in a cauldron before being pounded while still hot and made into a flat shape. Boiling water or coarse green tea is poured over it before eating.

“Saba-zushi”, ubiquitous at festivals in the northern mountains and highlands

In the south, people caught and ate fish from the Seto Inland Sea. In the north, however, people ate river fish and salted fish from the Sea of Japan (East Sea).

All photographs courtesy of Rural Culture Association Japan

Omachi rice, a well-known type of sake rice (called sakamai), was first cultivated by the innovative farmer Jinzo Kishimoto, who noticed an unusual ear of rice and brought it home with him on his way back from visiting the Hoki Daisen mountain in 1859. By the middle Edo period, people in each village often took religious trips to temples, shrines, and

sacred mountains. It was often the case that Kishimoto found prime rice seeds during his excursions and brought them back home. The rice he found on this particular trip came to be called Omachi, named after the place he came from.

The central starchy part (called shimpaku) of Omachi rice is particularly round and large, making it ideal for sake brewing as it facilitates the production and fermentation of high-quality rice koji. Yamada Nishiki and Gohyakumangoku, two other leading types of sake rice, are descended from Omachi rice.

Securing sources of salt has been an important issue in Japan since ancient times. Though Japan is surrounded by sea on all sides, it took a great deal of effort to crystallize salt from the seawater (which has a salinity of 3%) in the rainy and humid climate. In order to concentrate the salinity of the seawater using natural wind and sunlight, agehama salt farms using water drawn from the beach and irihama salt farms using the ebb and flow of the tide were developed during the Edo period. During the Showa era, flow-down salt farms were developed. The coast of the Seto Inland Sea was well suited for salt pans due to the frequently sunny weather, and it was also possible to distribute large amounts of salt from there cheaply via the Seto Inland Sea maritime route. By the end of the Edo period, the area accounted for 80 to 90% of national salt production. Traditional salt farming came to a close in 1972 with the introduction of an inexpensive method of concentrating salt from seawater which uses electrodes and ionic membranes.

Okayama is known for its luxury fruits such as white peaches and muscats. The prefecture’s history of fruit cultivation was made possible by the ideal warm climate and the efforts of those who came before us.

With the introduction of the Shanghai and Tianjin varieties from China in 1875, full-scale peach cultivation and selective breeding began, leading to the creation of the new “Kinto” (“gold peach”) variety in 1895. In 1901, the white peach variety was created, and has since become synonymous with peaches in Japan. The protective bag cultivation technique, used to grow peaches that are both delicious and beautiful, was also developed in Okayama.

Similarly, grape cultivation began with the sale of government-owned forests in 1875, and in 1886, attempts at greenhouse cultivation commenced through a process of trial and error. In 1888, growers succeeded in harvesting Muscat of Alexandria. This variety is also synonymous with Okayama grapes to this day.

Column: A Land and Culture Created by Steel

In poetry, the word “Kibi” is often accompanied by the phrase “[the land that] blows magane iron”. “Magane” is high quality iron, while “blowing” refers to the tatara smelting process, which incorporates bellows. The Chugoku Mountains were a major steel-producing area from ancient times to the Meiji era, due to the nearby high-quality iron sand, iron ore production areas, and wood to supply fuel, as well as a developed transportation network.

Tatara smelting requires large amounts of iron sand and charcoal. The iron sand could be taken from earth and sand produced by breaking up mountain rock, but it represented only 1 to 3% of the resulting debris, with the rest being washed away into the river. As a result of this process, earth and sand accumulated near the mouth of the river, making the sea shallow, and eventually the land was reclaimed from the area called Kibi no Anaumi. To this day, place names like Hayashima, Tamashima, Kojima, and so on reflect how there were once islands (shima in Japanese) there.

The emergence of iron tools such as plows and hoes in ancient agriculture had an immeasurable impact. They also enabled massive civil engineering projects, such as the construction of burial mounds and irrigation canals.

Bizen is one of the “Six Ancient Kilns of Japan” and has the oldest history as a site of ceramic production—approximately 1,000 years. The defining feature of Bizen ware is that does not use any glaze or paint; it is simply baked in a kiln. As the finish changes depending on the qualities of the soil and changes in temperature, no single item of Bizen ware has the same color or pattern. Bizen ware is baked at a high temperature for about one to two weeks, making it so durable that it is popularly claimed that it will not crack even if thrown.

Shoya-mawashi, a method for selling medicines that formed the foundations for the current system of leaving medicines at customer’s homes to be paid for later, was developed during the Genroku period (1688–1704). This method involved a traveling apothecary depositing a general supply of medicines with the headman of a village, who would sell the medicine to the villagers as needed on the apothecary’s behalf. Hangontan medicinal pellets are famously associated with the apothecaries of Etchu-Toyama; however, Jokan Mandai, a traveling doctor from Bizen, introduced them to a retainer of the Toyama Domain with whom he became acquainted during a trip to Nagasaki, and sales then took off under the domain’s patronage.

Rush cultivation in Okayama Prefecture has ancient roots, and mats similar to tatami, woven from rush, have been excavated from an ancient burial mound dating from the first half of the 5th century. There are also other historical artifacts showing that rush processing techniques existed at the time, such as a record that a man from Bizen called Hata no Tora was awarded an official position in the 8th century due to his achievements in making tatami mats. By the end of the Muromachi period (1336–1573), tatami mats became essential for Shoin-zukuri architecture, and demand increased. During the Edo period, the domain itself encouraged the cultivation of rush as a commercial crop, and it became a specialty of the area. During the Meiji era, hanamushiro floral-patterned mats made from processed rush became one of the top ten exports of Japan, being exported to countries all over the world.

The kojin religious tradition thrives in the Seto Inland area, and especially in Okayama Prefecture. The concept of kojin (“wild god”) results from a fusion of Buddhism, Shinto, and indigenous beliefs. When the gods left for Izumo in October, kagura dances were performed for the kojin to keep it from going on a rampage. Today, Bitchu Kagura is centered on a dance with a strong performative element that was created by Kokkyo Nishibayashi (a Japanese classical scholar of the late Edo period) and draws heavily from the myths of the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki.

Saidaiji is a historic temple that was founded in 751. This is where the Saidaiji Eyo is held—a very unusual festival that takes place on the third Saturday of February every year, during which crowds of about ten thousand mostly-naked men jostle for a pair of shingi, auspicious wooden sticks. This is said to have originated from the New Year in 1510, when shingi were thrown to masses of worshippers flooding in to receive paper talismans called go’oshi. The man who is granted the shingi after a hard-won battle is called a fukuotoko, or “lucky man”, and customarily sticks the shingi into a mountainous heaping of new rice placed into a masu, traditional wooden cup used for measuring rice. The rice overflowing from the masu symbolizes good fortune that will bring a bountiful harvest and many descendants.

Right:“Masu Cup of Auspicious Rice from the Eyo Festival”

Photographs courtesy of Saidaiji Temple Above:“Eyo, the Peculiar Festival of Saidaiji” (Okayama City)

Below:“Masu Cup of Auspicious Rice from the Eyo Festival”

Photographs courtesy of Saidaiji Temple

Column: The Sanyo Route and the Seto Inland Sea Route

The Seto Inland Sea route has been the main maritime route connecting northern Kyushu and the old central capital region (Kyoto, Nara, and surrounding prefectures) since ancient times. The ritsuryo state (the early centralized Japanese state) established administrative areas called the Shichido (“seven routes”), based on routes for land traffic, and began

developing post houses and other means to facilitate travel. However, by the 8th century, maritime transport had overtaken land transport due to its superior capacity, and the Seto Inland Sea route once again became the main logistics route.

It is also said that by the end of the Heian period (794–1185), Taira no Kiyomori improved the ports and carried out excavations at Ondo no Seto to enable trade between Japan and Song China. During the Muromachi period, trade between Japan and the Ming Dynasty of China also took place on the Seto Inland Sea route.

When the Five Routes were established in the Edo period, the Sanyo Route was designated as an auxiliary route, but it came to be used by the feudal lords of western Japan during their journeys east to take turns attending to the shogun. On the Seto Inland Sea route, Tamashima, Shimotsui, Ushimado, and other ports prospered as transit points for kitamae-bune cargo ships. The Asahi, Yoshii, and Takahashi rivers also developed as transport routes, and the Kurashiki River, a tributary of the Takahashi River, was developed into a canal, turning Kurashiki into a commercial center. Large-scale development of new rice fields was carried out on reclaimed land, and cultivation of commercial crops such as rice and wheat, as well as cotton, rush, rapeseed oil, and soybeans flourished. In particular, cotton cultivation encouraged the development of the cotton weaving industry and the development of a commodity economy, but for this, the herring oil fertilizer transported from Hokkaido by kitamae-bune cargo ships was essential. With the growth of Osaka as an economic center and development of the westward sea route, the shipping economy of the Seto Inland Sea grew by leaps and bounds.

Though sailboats still traveled the route until the early Meiji era, advances like the advent of steamships and development of the Sanyo Railway in the third decade of the era (the late 1880s on) meant that the old ports of call gradually declined. On the other hand, light industries developed in the urban areas, such as the textiles industry, which grew from

the Edo-period cotton weaving industry. The chemical industry and the shipbuilding industry followed, leading to the growth of the post-war heavy chemical industry now located in the coastal area.

With developments like the opening of Okayama Station on the Sanyo Shinkansen line in 1972 and the Great Seto Bridge in 1988, Okayama has become a modern transportation hub in the eastern Chugoku region, with access to and from all directions.