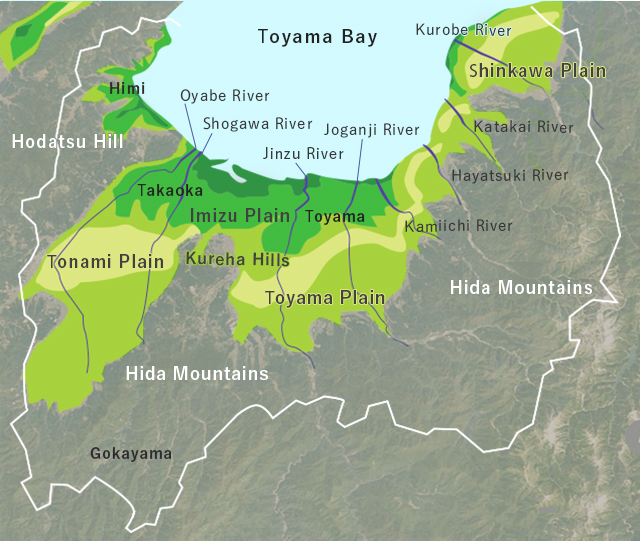

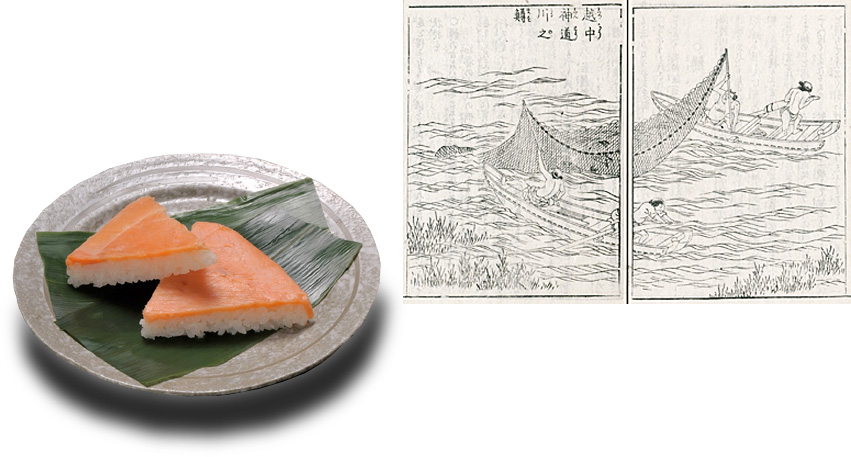

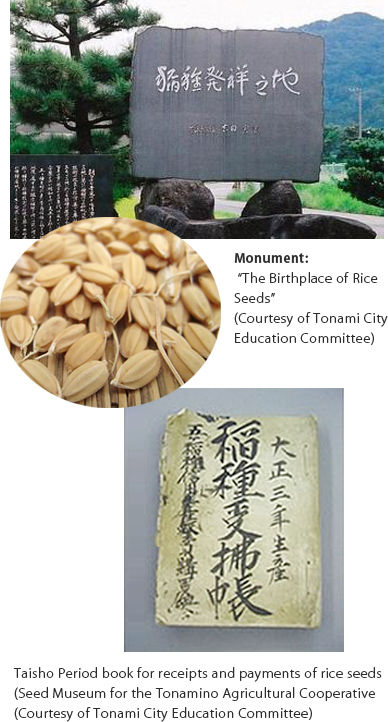

Toyama is a major producer of rice seeds. Rice seeds of approximately 50 different cultivars are exported from Toyama to 44 prefectures across Japan. There are various theories about how this trade began, but some say that production began with encouragement by the Buddhist priest Shakunyo, who built the Zuisen-ji Temple. In the late Edo Period, Toyama’s medicine peddlers would take on contracts to serve as middlemen for the rice seed trade, and Toyama rice seeds became prized throughout Japan.

Toyama rice seeds have a number of indicators of high quality: they have a high germination rate of over 90%, they are very pure genetically, they are very fertile, and they suffer little damage from disease and pests. This makes them trusted by customers in the agricultural industry across Japan.

To maintain this high quality, prefectural agricultural laboratories select cultivars suited to Toyama’s climate, perform research into cultivation techniques, and disseminate their findings. At the Agricultural and Forestry Promotion Center, seed inspectors appointed by the prefectural governor examine seed fields. Additionally, once the seeds are harvested, agricultural cooperatives carry out examinations of the produce, and perform germination tests, DNA appraisals, and so on. Only rice seeds that pass these rigorous inspections are accepted as Toyama rice seeds.