Stretching from north to south and surrounded by the sea, Japan's culinary culture has developed based on the four seasons and is centered on savoring the seasonal blessings of the foods of the fields, mountains, and sea.

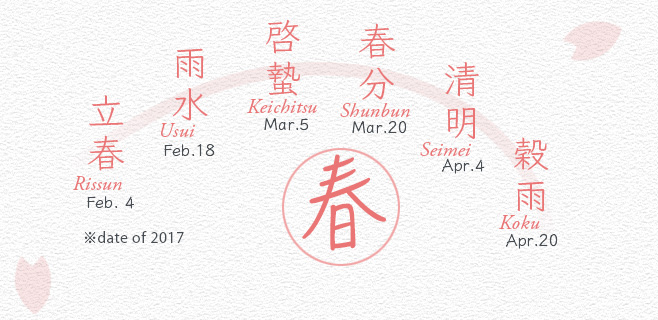

From ancient times, the Japanese have valued seasonality as an important part of daily life and have referred to various calendars as a way to enrich their lives. Calendars, such as nijushisekki (24 solar terms) which indicate different stages of the seasons such as risshun (start of spring), geshi (summer solstice), and shunbun (autumnal equinox), and shichijuniko (72 pentads) that express more subtle seasonal shifts is deeply related to the Japanese food culture, used as a guide to follow the seasons and to practice agriculture.

In "Teishoku of the Seasons," we'll be sharing the appeal of enjoying seasonality through the seasonal foods used in teishoku, an everyday meal for the Japanese, as well as introducing the relationship between the ancient calendars (handed down to present day) and the food culture.

Spring represents the first, second and third months of the lunar calendar—the period between risshun (start of spring) and rittō (start of summer) under the calendar's 24 divisions, or terms. These days, where April has become the major turning point, we have an impression of spring starting when the cherry trees begin to blossom, but in the lunar calendar, spring is what we call this most beautiful of seasons where we can experience the transition from the bitter cold of winter to the glorious warmth of spring with all five senses.

The dry, piercing, cold winds gradually give way to warm, dewy air, the plants begin to spring up, the sleeping animals begin to stir...

...Yes, the liveliest season of the year is beginning.

Risshun is the first of the 24 terms of the lunar calendar. Taking place at around February 4 each year, many Japanese remember it as "the day after Setsubun." Naturally, the name "Setsubun" itself refers to the separation (bun) of terms of the lunar calendar (setsu). Risshun is the first day of a new year, when the calendar term truly does change. Even nowadays, where we use the Gregorian calendar, we still refer to New Year’s Day using words that are remnants from our time using the lunar calendar, such as shinshun ("new spring") and geishun ("welcoming spring").

The word risshun - start of spring - may conjure up images of warm, mild days, but the truth is quite the opposite. Risshun is in fact the coldest day of the year, and it is from this day that the cold gradually seems to thaw.

As such, don't take risshun to be the day to change into lighter clothing - instead,

keep yourself

warm while you wait for the coming spring.

It's just a little bit longer until we can welcome spring,

the time of year that truly brings every

Japanese person to life.

Chirashi-sushi is a standard of the Hinamatsuri ("doll festival") menu. It's popular for its colorful appearance and sweet seasoning that make it easy for children to eat.

Much like with the osechi eaten during the New Year's holidays, the plentiful servings of ingredients are all packed with meaning: the prawns symbolize a wish to live long enough to be bent over in the same shape, the lotus roots express a wish to have a clear view of the future, and so on.

Clams were used in a game played with shells during the Heian period, and because one shell cannot fit perfectly without its opposite piece, they have come to represent happy marriages.

This is a symbol of good fortune, with a wish to spend life happily married together at its heart.

Hichigiri is a Japanese confection often seen in the traditional sweet shops of Kyoto during this season.

The part that juts out represents a shell based on the pearl oyster, which, true to its name, produces pearls.

When people talk about Setsubun, the first thing they think about is the practice of scattering beans while shouting "Demons, out!". This happens in Kyoto too. What's interesting is that, after having eaten a number of beans that matches the years of their life with one extra added, Kyoto people wrap the remainder in traditional writing paper, then rub the resulting package against their bodies and throw it over their shoulders while making a wish to become smarter or to be healthy.

Taking the beans to offer to the local Shinto guardian after cleaning up the next day is a regular Setsubun custom. Recently, the custom of eating ehomaki sushi rolls, said to have originated in Osaka, has become a nationwide staple of the event, but I hear that in old Kyoto, this was exclusively practiced in the geisha districts such as Gion.

Speaking of Setsubun food, salt-grilled sardines and honaga-jiru soup spring to mind. In contrast to the lively bean-scattering custom, these don't have the splendor of a meal for a fine day, but they are important customary dishes. The dried daikon radish strips of honaga-jiru, packed with sweetness and a savory taste, blend with the red miso soup to

provide a very agreeable flavor.

I hope to that we can continue to carry on these customs as Japanese traditions.

The smell of the smoke that comes from the sardines as they're grilled was said to help drive away demons for Setsubun. Enjoy with a good squeeze of kabosu, a citrus fruit similar to yuzu.

I remember wondering "Why do we eat sardines for Setsubun?" as a child while eating this. This year, I invite you to enjoy this sardine dish with your children as you

tell them about Setsubun and the reasons why we eat these dishes.

As risshun now falls on New Year's Day, Setsubun now falls on New Year's Eve.

On New Year's Eve, we eat toshikoshi soba - the long, slender noodles a symbol of fortune representing a long life - and so on risshun, we want to continue that custom. For risshun, we eat honaga-jiru soup, which features strips of dried daikon radish. The

dried daikon is cut into long strips like soba noodles, and enjoyed in a red miso soup.