Stretching from north to south and surrounded by the sea, Japan's culinary culture has developed based on the four seasons and is centered on savoring the seasonal blessings of the foods of the fields, mountains, and sea.

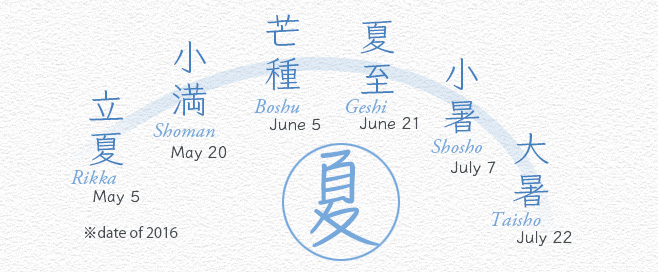

From ancient times, the Japanese have valued seasonality as an important part of daily life and have referred to various calendars as a way to enrich their lives. Calendars, such as nijushisekki (24 solar terms) which indicate different stages of the seasons such as risshun (start of spring), geshi (summer solstice), and shunbun (autumnal equinox), and shichijuniko (72 pentads) that express more subtle seasonal shifts is deeply related to the Japanese food culture, used as a guide to follow the seasons and to practice agriculture.

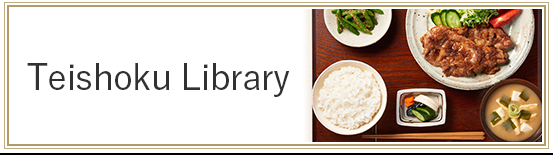

In "Teishoku of the Seasons," we'll be sharing the appeal of enjoying seasonality through the seasonal foods used in teishoku, an everyday meal for the Japanese, as well as introducing the relationship between the ancient calendars (handed down to present day) and the food culture.

Summer in nijushisekki which divides the calendar into 24 solar terms begins from early May.

This period right before the rainy season is marked by a rise in temperature and humidity,

and the rapid growth of plants and animals.

In the fields and hills, new greenery becomes even more lustrous and vibrant,

and frogs in the paddy fields begin to sing in full-force.

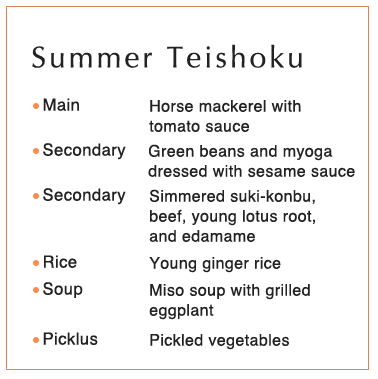

Summer in nijushisekki is from early May to early August. Getting enough nutrients from a savory teishoku is ideal during this season when we frequently sweat and our appetite subsides. In Japan, various foods reach their peaks with the change of the seasons. Summer is all about the succulent vegetables. Vegetables—usually presented in a basket - that has flourished under the bountiful sunlight is packed with nutrients that helps recover from summer fatigue. Here we'll be introducing a summer teishoku that incorporates plenty of seasonal foods that are not only at the peak of their flavors but also high in nutrients and are cost-efficient.

Green beans during this season is especially juicy, tender, and flavorful. The dish combines the distinctively Japanese vegetable myoga with green beans to create a rich sesame sauce aemono (dressed dish).

An outstanding side dish, aemono is a traditional cooking method - which requires time and effort - that enhances the flavors of the seasonal vegetables. The fragrant sesame dressing brings out the natural flavor of the green beans cooked to a perfect texture

Rice is a typical food that symbolizes the arrival of early summer. Rice cooked with juicy young ginger chopped into fine strips - its mild flavor limited to this season -, abura-age (deep-fried tofu), and bonito soup stock, results in a fluffy texture and a mellow-flavor.

Young ginger also promotes metabolism, perspiration, and increases appetite. Takikomigohan (seasoned rice cooked with a variety of ingredients) is a great way to savor and enjoy young ginger.

A colorful dish with horse mackerel, fresh and fatty from June to August, deep-fried for a crispy finish and marinated in ripe, bright red tomatoes grown in the sun.

The small amount of citrus jam brings out the natural flavor of the tomatoes, resulting in an appetizing balance of sweet and salty fitting for the summer. Served with a sprinkle of shiso, Japan's refreshing aromatic herb.

Hangesho is one of the divisions of the Shichijuniko (72 pentads) that refers to a period in early June. There are various theories on the origin of this name. Around the end of the rainy season, this period sees the blooming of small white flowers of a leafy plant called hangesho (part of the Saururaceae family). The leaves closest to the flower turns partially white which is why this plant is also referred to as "Hangesyo" (a homophone written in different Chinese characters that can be translated into "half-makeup"). This period is also the season when a medicinal herb known as hange (karasubishaku) grows.

For farmers whose daily lives are deeply rooted in the calendar, rice planting needs to be completed during this period. Otherwise, the rice will not grow and the fields will yield significantly less crops in the fall.

During this period which corresponds with the last stages of the rainy season, there is a custom mainly in the Kansai region (southern central region of Japan) of eating octopus. Farms that finished planting during Hangesho originally practiced this in hopes that the rice would settle its roots firmly into the earth like an eight-legged octopus, and lead to a good harvest. The anticipation of the farmers, who hoped for the paddy fields and the rice to endure the rainy season and yield a bounty of crops in the fall, is reflected in the food culture.

Slow-cooked, tender octopus, young taro, and okura served cold in a bowl. The delicate texture of the young taro and the crunchy okura which signals the arrival of summer bring out the flavor of the fresh octopus

Octopus is rich in taurine which relieves fatigue. This nourishing dish with a mellow taste is fitting during this season when our bodies are affected by the heat and humidity.