Stretching from north to south and surrounded by the sea, Japan's culinary culture has developed based on the four seasons and is centered on savoring the seasonal blessings of the foods of the fields, mountains, and sea.

From ancient times, the Japanese have valued seasonality as an important part of daily life and have referred to various calendars as a way to enrich their lives. Calendars, such as nijushisekki (24 solar terms) which indicate different stages of the seasons such as risshun (start of spring), geshi (summer solstice), and shunbun (autumnal equinox), and shichijuniko (72 pentads) that express more subtle seasonal shifts is deeply related to the Japanese food culture, used as a guide to follow the seasons and to practice agriculture.

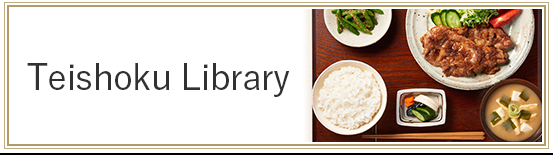

In "Teishoku of the Seasons," we'll be sharing the appeal of enjoying seasonality through the seasonal foods used in teishoku, an everyday meal for the Japanese, as well as introducing the relationship between the ancient calendars (handed down to present day) and the food culture.

Winter represents the 10th, 11th and 12th months of the lunar calendar, occupying the period between ritto (start of winter) and risshun (start of spring) under its 24 terms. This is the season where the sun is at its lowest during the year, and the nights are at their longest.

This is the time when the animals get ready to hibernate and pass the winter, and when we become fond of the kotatsu and the heater. Let's greet the new year with a sacred feeling, looking back on the year that has passed and bringing it safely to a close with a variety of traditional customs, such as the yuzu bath we dip into on the winter solstice.

Ritto: November 7 (2016), 19th day of the 10th month of the lunar calendar Ritto (start of winter) is the 19th of the 24 terms of the lunar calendar. One can feel the arrival of a chill in the mornings and evenings, and on this day of the calendar, winter begins. In the 72 pentads - a further division of the 24 terms into five-day units - this is the period when the sazanka camellia shrub begins to flower, the earth freezes, and the narcissus blooms. The ri component of the word ritto refers to the start of a new season, and together with risshun (start of spring), rikka (start of summer), and risshu (start of autumn), it is part of a group of four called the shiryu. In China, there is an adage which says, "for the winter starting from ritto, one should feed the body with food that is in season." We too should make sure that we're properly fed so that we can pass the long winter in good health.

Daikon is a common sight throughout the year, but winter is its original season.

It's best known for being delicious whether grated, boiled, or pickled, and it was once called an "edible panacea" because it was held to be effective against loss of appetite, sore throat, and even constipation.

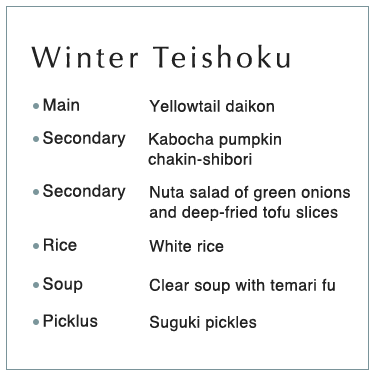

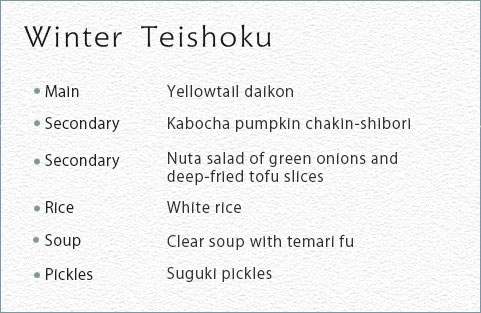

Yellowtail daikon pairs this vegetable with simmered fatty yellowtail (Japanese amberjack).

The dish offers plenty of daikon, which takes the lead role.

Suguki pickles are made from a kind of turnip picked in the Kamigamo area of Kyoto. These pickles are a winter staple in Kyoto, where they are enjoyed for their mild sourness and their crunchy texture.

"Fu" is mainly made from protein and gluten extracted from wheat flour using water.

"Temari fu" is a type of fu that has been shaped into charming, colorful ball shapes that call to mind special days like New Year's Day or Momo no sekku (the 3rd day of March, also the Doll Festival or Girls' Day). This is one of a rich variety of stylized fu

that includes sho-chiku-bai, hagoita, and a gourd, and is often used in zoni soup and other special New Year dishes (osechi).

Originally, this festival was a rite of the imperial court, and its name refers to the first tasting of newly harvested rice. On November 23, the Emperor offers newly harvested rice and other staple grains to the gods of heaven and earth, and partakes of the offerings himself, to give thanks for the year's harvest.

Japan has long had customs to

celebrate the harvest of staple grains, and the associated religious services are believed to have started in the Asuka period. In modern times, these are also called harvest festivals to celebrate not just grains, but all the blessings of nature, and events take place all over Japan to enjoy the flavors of the seasonal harvests. To sample the flavor of freshly

harvested rice, we recommend the use of an earthen pot, which can slowly cook it right through to the core with the effects of far-infrared heat.