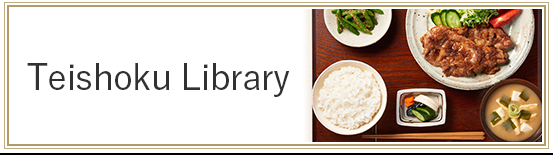

In the days when there were few places to eat out,

if people had to be away from their homes for long hours or when they were

traveling,

portable meals were common. In Japan, special containers were developed

to

make these portable meals easier to carry.

The foods were prepared in various ways and arranged in a way that

considered

the colors of the ingredients, with the added touches of seasonal

elements.

This evolved into a unique Japanese food culture, which is now so popular

that

the word “Bento” has become a well-known proper name overseas.

Here, we present Japan’s bento culture in various eras and scenes,

together with the characters that appear in those scenes.

These battles were hard-fought struggles for survival, and the thoughts of the commanding daimyo, or lord, would greatly influence their officers and soldiers’ morale. Rationing played a key role in the Sengoku daimyos’ military command. It was during this period that battles became constant, grew to massive scale, and became widespread, and the stable supply of rations would be a determining factor for the various levels of society in one’s territory to be able to participate in battle, showing the real power of the daimyo. In addition to supplying rations to the front lines, they also stockpiled rations in castles that were not in a state of war so as to prepare for emergencies.

– Mohri Museum collection

Mori Motonari (1497–1571) was a Sengoku daimyo who was praised as “hero of the Sengoku Era,” won over 200 battles during his lifetime, during which time he conquered eight domains in the Chugoku region. He also enjoyed mochi(rice cake), and supported its use for rations as well. In the Intoku Taiheiki, a regional history account, it is noted that the soldiers set out with a bag of mochi, a bag of rice, and bag of fried rice tied to their waists.

Mochi is highly portable, keeps well, and a small amount provides energy and fills the stomach to the extent that it has inspired the Japanese idiom “a bellyful of mochi lasts for three days”. The sugars contained in mochi act on the brain, which helped to sharpen the soldiers’ fighting instincts. One could describe it as an ideal ration for soldiers who need to maintain their stamina. Motonari Mori prepared mochi and sake not only during times of war, but also during peace as well, and he would often talk with people, even those of low status, and casually treat them to food and drink. It is said that his retainers would visit him bringing Seasonal flowers, vegetables cultivated at home, and fish and fowl as gifts.

– Yonezawa City Uesugi Museum collection

Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578) was known as the Dragon of Echigo, and over about 70 battles, he was only defeated once, at the Battle of Kawanakajima. His subordinates would learn whether they would be heading out into the field from what he ate. He was typically a frugal man who ate simple meals of one soup and one dish, but ahead of a battle, he would cook a mountain of rice and treat his subordinate officers and soldiers to feasts fit for a king.

There would be black-boiled abalone, vinegar-washed fish and jellyfish sashimi, soups with seasonal vegetables and dried fish, walnut-roasted duck, simmered sand borer, and more—all sorts of rare delicacies. Uesugi Kenshin’s subordinates, who experienced his frugality on a daily basis, would be delighted, and these feasts strengthened their esprit de corps and morale. These feasts served in hopes of raising the victory cry later came to be known as Kenshin’s kachidoki-meshi, or “victory cry meals”.

Photograph courtesy of: Joetsu City Tourism Exchange Promotion Division

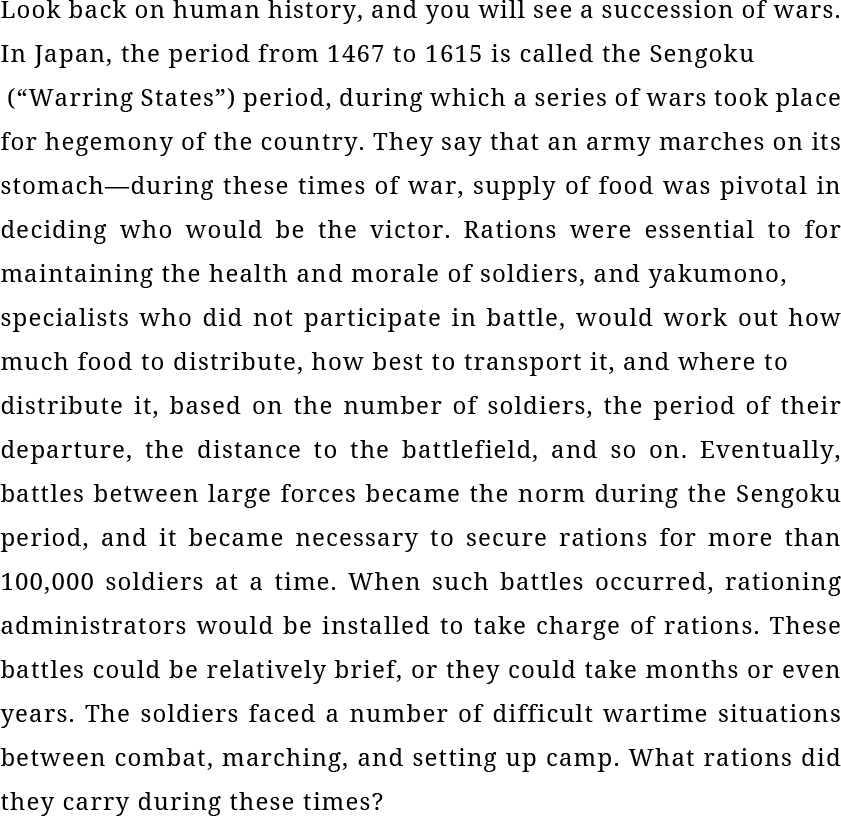

In battle, it was vital to be prompt and precise about how rations were brought to the battlefield. Supply units called konidatai (supply convoy) took on this important responsibility. The members of these units were called jinpu (or bumaru) and were recruited from the peasant population to serve as non-combatants at the rear end of army lines, where they transported resources like rations, munitions, and construction tools. It was also vital to secure transport routes over land and sea to procure rations. Additionally, sometimes armies would buy food from farmers and merchants near the battlefield.

“Zōhyō monogatari” – Tokyo National Museum collection

– Kofukuji (Kyoto) collection

Hashiba Hideyoshi (1537–1598; name changed to Toyotomi Hideyoshi from 1586) was a resourceful general. He rose from peasantry to serve Oda Nobunaga, and rose to prominence with his crafty strategies and policies. Two of his most stunning maneuvers were the Grand Return from Chugoku (Chugoku Ogaeshi) of 1582, when he covered a distance of approximately 230 kilometers from Takamatsu in Bicchu Province to Kyoto in just 10 days after learning of the death of Nobunaga, and the Grand Return from Mino (Mino Ogaeshi) of 1583, when he traveled 52 kilometers from Ogaki to Nagahama during the battle with Shibata Katsuie in just five hours.

During the Grand Return from Chugoku, Hideyoshi rested at Himeji Castle, where he replenished military supplies and distributed all the rations and money kept at the castle to all of his subordinate officers and soldiers. This demonstrated to them Hideyoshi’s strong tenacity of purpose, and provided them with reassurance and a boost to their morale. During the Grand Return from Mino, Hideyoshi sent his subordinates to the villages along the way a few hours ahead to command the peasants: “Cook rice and give it to the soldiers passing by. Do so, and you will be rewarded tenfold at a later date.” And so, in every village on the way, rice balls were made and lined up along the highway, and the soldiers ate them as they ran along. This was how Hideyoshi secured rations, won the struggle for power within the Oda clan, and gained the position of Nobunaga’s successor.

In the latter half of the Sengoku period, tactics of overwhelming the enemy with mass mobilization of soldiers became increasingly common. Between equipment for soldiers, guns and munitions, rations, horse feed, transportation costs, and so on, it is estimated that the cost of one battle would amount to somewhere between 100 million and 300 million yen in today’s money. Furthermore, the longer a battle took, the more expensive it became to pay to feed soldiers and horses. How were the military funds for this procured? The main income for the daimyos came in the form of annual land tax and temporary taxes collected from their territory, but at times, they would use their income as collateral to borrow rice and money from wealthy merchants in order to supply their armies. However, that alone was not enough.

Mori Motonari used silver from Iwami Ginzan, a silver mine in his territory, to raise military funds. Iwami Ginzan silver was of high quality, produced in abundance, and had high economic value, so the daimyos would often fiercely contest the territory. In 1562, when Motonari won the battle for the silver mine against the other nearby daimyos, he declared that all income from the mine would be used for war expenses, and sent the silver to procure rice in areas where he had no means to transport rations himself. He also used the silver to procure guns and gunpowder through the Nanban trade (trade with the Portuguese).

Kenshin Uesugi, meanwhile, raised funds by cultivating and exporting ramie, a type of hemp yarn used to make textiles. The Echigo region’s ramie was of very high quality and prized by the court nobles of Kyoto, where it was a rare favorite of the upper classes. The profits Kenshin obtained from careful control of its distribution were used for military funds. He also had mines in the mountains that produced an abundance of mineral resources.

Hashiba Hideyoshi was not only a strategist — he was also a shrewd businessman. He set up areas under his direct control to stockpile supplies, and built up relationships with merchants to have them procure additional supplies. He also closely watched the market price of rice to buy low and sell high. During times of war, resources were carried from the stockpile areas to the various battlefields, where Hideyoshi had the merchants set up markets selling goods collected from all over the country. By doing so, they saved money on transportation costs. After the merchants made a tidy profit, taxes were collected from them according to their earnings. Hideyoshi also took out a number of loans with interest. After his attack on Bicchu Province in 1582, Iwami Ginzan was placed under his control, and the mine was required to pay business taxes.

It is impossible to fight wars without military funds. And so, the daimyos devoted their efforts to fortifying stable economic power within their territory. Their battles could not be won by martial strength alone.

Iwami Ginzan silver was discovered at the end of the Kamakura period (1192–1333), and the abundance of the mine, with an average annual output of 38 tons, was renowned even outside of Japan. That much silver would exceed a million koku of rice in value (one koku = about 150 kg of rice). Following the Mori clan, which had won the dispute for the territory, the mine came under the control of Hideyoshi, after which it was seized by the Tokugawa shogunate. Until the middle of the Edo period (1603–1867), Iwami Ginzan supported the huge demand for silver in the Japanese economy.

The mine was sold off to the public during the Meiji era (1868–1912), and later closed off in 1943, when flood damage caused the mine tunnels to be submerged. In 2007, the mine was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its environmentally-friendly production methods and its cultural landscape that existed in harmony with nature.

The Sengoku period is filled with heroic tales of famous generals, but most of the people who actually fought on the battlefield were common soldiers. These soldiers were either mercenaries or peasants who responded to calls for conscription. They were important workers not only in the actual fighting, but also in duties like setting up camps and positions, and handling incidental tasks. Though typically they provided their own food, in the case of situations like prolonged battles, they were paid one sho of water, six go of rice per person per day, and one go of salt per ten people, two go of miso per ten people in 3-to-4-day instalments. (One sho is equivalent 1.804 L; one go, 180.4 mL). For battles taking place at night, a greater amount of rice was provided. However, with the battlefield environment and wartime conditions being extremely harsh, it was not uncommon for people to be forced to fast. The book Zōhyō monogatari (“Tales of Common Soldiers”), published during the early Edo period, details the wisdom of the battlefield. It gives an easy-to-understand description of the knowledge and ingenuity the common soldiers relied upon to survive through accounts of their experiences.

Rice and Uchigaibukuro

Most of the provided rice came in the form of unpolished rice. Some would be cooked for the day’s food, and the excess would be set aside to prepare for unforeseen circumstances. Additionally, the cooked rice was not eaten all at once, but rather made into single-meal rice balls that would be carried by the soldiers. This satisfied the key requirements of packed food: that it must be light, compact, and readily preservable. Aside from rice balls, the rice could be left in its husks or quickly cooked to make dried boiled rice or parched rice to carry. During war, the soldiers would not know when or where they would be able to eat. It would also be disastrous to drop one’s food or have it seized by an enemy. This led to the development of the uchigaibukuro. An uchigaibukuro was a tube-shaped cloth bag of about 3 meters in length containing foods like rice balls and dried boiled rice, as well as medicines. Each meal would be bundled up into individual knots fastened by a cord, and the bag would be worn around the body at all times. This made it easy to take out food while out marching or in the darkness of night, and even should part of the bag be torn, the entire contents would not spill out.

Water

Water is essential to life. The soldiers would carry bamboo tubes of water, but this was not enough by itself. They would sweat a lot during their fierce battles, making it thirsty work. However, they had also been strictly warned against drinking well water while in enemy territory. This is because when enemy soldiers withdrew from an area, they would keep their opponents from using the wells by contaminating the water with poison or filth. River water was considered safe, but there was still a risk of water poisoning when traveling far afield, so the soldiers were taught to mix oil made from apricot pits into the water, or to dry pond snails from the rice fields, put them in a pot of river water, then drink the upper layer of liquid that was produced. Otherwise, soldiers also drank rainwater, or took muddy water from puddles and strained it through a cloth bag to make it drinkable. Additionally, when searching for sources of water, soldiers would look for places where birds and animals gathered, or where there were many signs of their footprints.

Salt

As fighting involves manual labor, salt intake was also important. Unlike the granular, white salt of today, soldiers carried dark blocks of solid salt that had been baked and hardened. Powdered salt easily absorbs moisture, and if it takes on a lot of moisture, it will simply turn into a sticky solution that melts away. These solid blocks of salt were made by baking about 3 sho of salt at a time in a big salt kettle. (One sho = 1.804 L.) If for use by one person, a block would last for about 50 days, and it is said that the salt was even used as a substitute for money on the battlefield.

Miso and Imogaranawa

Miso is a nutritious foodstuff that is rich in high-quality amino acids, resulting from fermentation, various vitamins, calcium, and other nutrients. In Japan, there is a saying that one bowl of miso soup gives you the strength to walk for miles. The soldiers could lick unprepared miso or apply it to other foods, making it a supplementary source of protein and salt that not only aided stamina, but also sharpened the mind, improving concentration and quick-witted thought.

Miso would be dried or baked into miso balls, which were wrapped in bamboo skin or cloth and carried by the soldiers. Military commanders knew the effects of miso well. In order to secure a source of miso, Date Masamune built a large miso brewery nearby his castle and worked hard to produce it. Meanwhile, Takeda Shingen developed jindate miso (“battle formation miso”), a type that matures in about 20 days. For this kind of miso, the soybeans were boiled and mashed, and then mixed with koji to make dumplings. The soldiers would carry the dumplings on their waists, which would ferment as they marched, resulting in a miso that was just right.

Outside of fighting, the common soldiers were also responsible for a number of odd jobs. To keep their supplies of miso from getting bulky, they would form them into imogaranawa ropes, which would always be wrapped around their waists. These were made by drying taro stalks and weaving them into a rope before boiling them in miso and allowing them to dry out. The common soldiers could get a lot of use out of these ropes by carrying them on their person, as they could be used just like normal rope for various needs. If the soldiers had to carry something, they could use their imogaranawa to help, and once their work was finished, they could cut off a piece and use it to make miso soup. The dried taro stalk would absorb water and swell up, becoming the base for the soup.

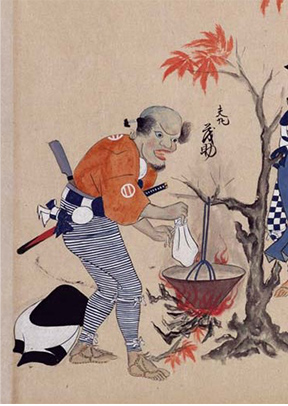

The white-and-indigo bag hung from the soldier’s neck is an uchigaibukuro. It has been packed with individual separate meals so that they can be easily taken out. Around the soldier’s waist is an imogaranawa rope.

Pickled plums, pepper, and chili peppers

There were other things that the common soldiers always carried, but these foods were not there to satisfy their hunger. These were pickled plums (umeboshi), pepper, and chili peppers. The common soldiers would put the pickled plums in the bottom of their uchigaibukuro and take them out when short-winded in a harsh battle—they were a welcome sight. As they gazed at the pickled plum, they would salivate, quenching their thirst a little.

The soldiers would only be given one pickled plum when they set off for battle, which they kept as a precious luxury during their deployment. Rather than tasting or simply eating it, they refrained and simply used it as inspiration when out of breath. In the case of pepper, the soldiers would chew on individual grains every morning both in summer and winter. Doing this helped them withstand both the heat and the cold. The freezing chill of winter was unbearable, however. To keep from freezing, the common soldiers would mash chili peppers into a paste and apply it from the buttocks down to the tips of their toes. Of course, getting chili pepper in one’s eyes would result in irritation and pain, so the soldiers avoided applying it to their hands. The common soldiers were only temporary hires, and they were provided almost nothing no matter how effective they were. They had to rely on wisdom and ingenuity to survive.

The common soldiers would be supplied with basic chest armor and jingasa helmets, which were wide-brimmed with a dish- or bowl-like shape. When cooking, the soldiers would use their jingasa, turned upside-down, as a cooking pot. The helmets were made of thin iron or leather, and the conical shape made them good cooking pot. Cutting a knot off from the uchigaibukuro around their necks, the soldiers would then put a bundle of rice into their makeshift pot and cook the rice into a soft porridge that was gentle on the stomach.

They would also cut just a piece off from their imogaranawa rope, add it to the pot with some water, and heat it to make miso soup. One piece of imogaranawa would be enough to make about 10 servings of miso soup. The soldiers always looked forward to eating, but because the rope would be soiled with sweat and mud, and it would reek of body odor mixed with old miso, it was far removed from fine dining.

“The field of battle is without exception a place of famine” is a phrase that appears in Zōhyō monogatari. The reality of the battlefield was indeed harsh enough to be compared to a famine, and there was an urgent need to have good knowledge of rations. As soldiers marched, they would pick up edible grass and nuts, as well as roots and leaves, and secure them to their horses to keep for later as food. If the rice kept in their uchigaibukuro absorbed moisture and sprouted as the result of heavy rain or river crossings, they would allow it to grow and ate it boiled with the roots. They also boiled pine bark, discarding the excess and eating the remainder as porridge.

In order to fight, soldiers needed to not only satisfy their hunger, but also eat sufficiently nutritious food for stamina, food prepared for survival in emergencies, and food prepared to calm the mind and keep the brain active. And so, aside from day-to-day rations like rice and miso, soldiers also carried hyorogan, kikatsugan, and suikitsugan—“ration pills”, “hunger pills”, and “thirst pills”. These were originally eaten by ninja spies. It was the duty of the ninjas to gather information at the enemy camp and report back alive. They needed to be able to act calmly and swiftly without succumbing to the high stress of their duties. As a result, they devised foods to support their physical and mental health. The recipe to make ration pills are given in Rōdanshū, a book of Koshu ninja techniques, while the recipes for hunger pills and thirst pills are given in Mansenshūkai, another book of ninja techniques. These pills were valuable, as they were made using a number of expensive natural medicines. Rather than describing them as rations, perhaps it is better to describe them as medicines.

Ration Pills

Ration pills were made by kneading ingredients like buckwheat flour, soybean flours, and black sesame seeds with sake, honey, and so on, then repeatedly steaming the mixture and drying it in the sun to make pills. These pills were also compounded with dried bonito and sardine powder to provide protein, pine nut to provide fat content, and gardenia, ginger, and cinnamon. Some recipes added secret herbal ingredients unique to the various regions and families.

Photograph courtesy of Professor emeritus , Mie University, Makoto Hisamatsu

The ration pills were rich in sugar, giving them an immediate effect, and 5 to 7 pills a day helped to restore tired minds and bodies. The soldiers could even crush them and feed them to the war horses to restore their energy. The pills were also easy to carry, weighing only 20-30 grams.

Hunger Pills

Hunger pills are a convenient, portable foodstuff intended to aid endurance when one is forced to spend days in enemy territory, remaining on the move while watching the enemy's movements. These pills were effective at relieving fatigue and stress, calming the nerves, and promoting blood circulation. They were made from a mixture of ingredients like ginseng, grated yam, coix seed, buckwheat flour, wheat flour, and rice flour, and these would be ground together before being soaked in old sake and dried. In particular, there was a high proportion of ginseng, giving the pills a distinctive smell. With these large, starch-based pills, soldiers were able to stave off hunger by taking three a day after running out of food during a lengthy, grueling battle.

Thirst Pills

Thirst pills were designed to quench thirst and soothe sore throats, and they were also effective at preventing coughs. They were compounded using pulp made from pickled plums to encourage saliva production. To make these pills, crushed sugar and bakumondoto (a tuber used to treat coughs) would be made into a solution with a small amount of water, then mixed together with the plum pulp, kneaded, and rolled into shape.

| Ration Pills | Hunger Pills | Thirst Pills |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The ninjas’ survival depended on their self-preservation techniques. The Sengoku military commanders shared in their knowledge that being able to survive under any harsh conditions was the key to triumph in battle. Ration pills and hunger pills were made from expensive medicinal ingredients and were not to be consumed regularly, but instead kept for prudent, thrifty use when the time called. The effectiveness of these pills and the skill it took to make them were praised in the Imperial Japanese Ministry of War’s Nihon heishokushi (“History of Japanese Military Provisions”, 1934), which said that the pills were perhaps the greatest form of food that the Japanese had ever developed.

The soldiers of the Satsuma domain carried akumaki, pouches of glutinous rice wrapped in bamboo skin soaked in lye, during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s expedition to Korea in 1592. This packed food was similar to chimaki (bamboo leaves stuffed with glutinous rice and sweet or savory fillings), and had a texture similar to mochi without being very sticky. The high water content of akumaki makes it soft and keeps it from hardening when cooled, and also makes it very filling. Cooking with lye adds minerals and other nutrients, and the strong alkali also suppresses the growth of unwanted bacteria, which made the food keep better. Normally, dried rations had to be rehydrated or boiled before eating. However, akumaki were a radical development, because they could be eaten as-is. It is said that while the other domain’s armies exhausted their supplies of rations, the Satsuma army had bellies full of akumaki and high morale.

During the Sengoku period, rations were a pivotal deciding factor in whether an army would stand victorious or be defeated. Under the harsh conditions of war, all kinds of innovations were developed to make rations easier to carry and more effective. They crystalized the commanders and soldiers’ wisdom about survival. Truly, these packed foods were the backbone of wars. Today, this wisdom lives on in modern, peaceful times, in the form of preserved foods for emergency use, as well as emergency foods for when disasters have occurred—and akumaki remains popular in Kagoshima as a simple local confectionery that can be made at home.

Born in 1950. After working for Japan Airlines Co., Ltd. as a flight attendant on international routes, and later as a lecturer in the company’s cultural affairs department (providing instruction in serving customers), she established Human Education Service. Since 1997, she has worked as a special lecturer at the Japan Travel Bureau Foundation to improve hospitality in various fields of tourism and provide guidance on how to foster hospitality, and she has also served as a tourism promotion advisor and committee member for the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, the Japan Tourism Agency, and local government. Since 2009, she has worked as a part-time lecturer at the Takasaki City University of Economics and other institutions. Her work involves research of modern hospitality, and as well as traditional Japanese hospitality and dietary culture.