In the days when there were few places to eat out,

if people had to be away from their homes for long hours or when they were

traveling,

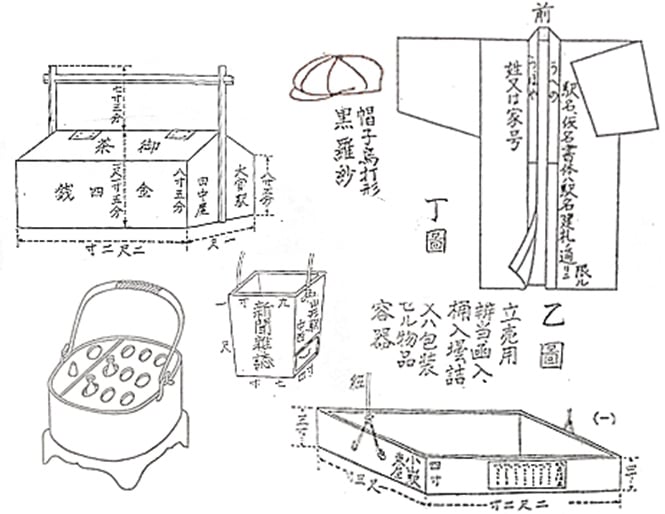

portable meals were common. In Japan, special containers were developed

to

make these portable meals easier to carry.

The foods were prepared in various ways and arranged in a way that

considered

the colors of the ingredients, with the added touches of seasonal

elements.

This evolved into a unique Japanese food culture, which is now so popular

that

the word “Bento” has become a well-known proper name overseas.

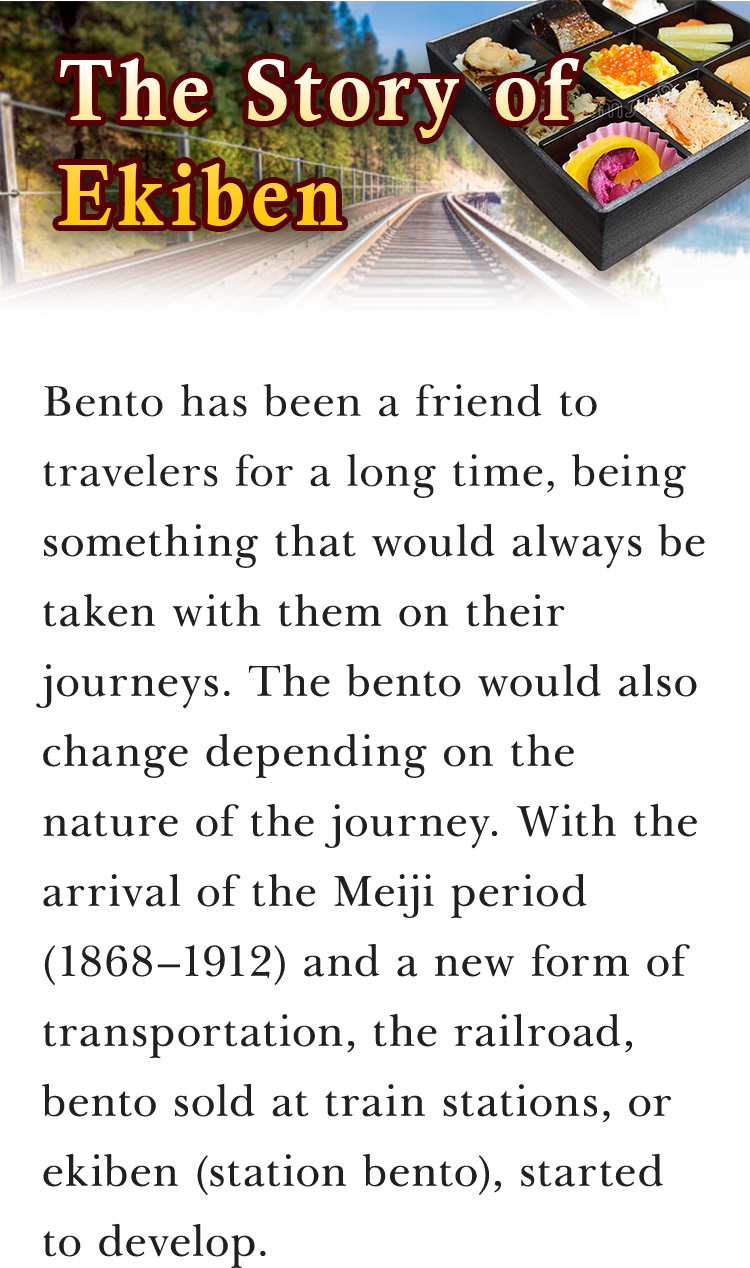

Here, we present Japan’s bento culture in various eras and scenes,

together with the characters that appear in those scenes.

People have been accustomed to eating ekiben during their journeys back in the day,

but now, ekiben products are attracting direct attention.

Ekiben fairs held across Japan are very popular events, with many people attending.

When traveling aboard the old steam trains, one would spend quite some time in transit. For example, it took an entire 3 hours and 30 minutes one way on Nippon Railway’s Ueno to Utsunomiya route opened in 1885, whereas it takes less than 50 minutes on the modern Shinkansen. Before electrification and high-speed came to the railroad, trains would also spend long periods of time stopping at each station, and it was a common sight to see people opening the windows to buy ekiben from vendors walking around the platforms.

Ekiben evolved with the development of railroads, and it is a manifestation of Japanese cuisine as well as an essential part of travel.

Here, we will look back at the history of ekiben.

There are various accounts of the first appearance of ekiben in Japan, but the most commonly accepted version is that ekiben first appeared at Utsunomiya Station in 1885.

There are records that Shirakiya, which operated an inn outside Utsunomiya Station, started selling bento at the same time that Nippon Railway’s (now JR East Japan) Tohoku Line Utsunomiya Station opened. This bento consisted of two sesame-covered rice balls and pickled daikon radish wrapped in a bamboo sheath, sold for 5 sen (an old unit of currency; 1/100th of a

yen).

This was quite an extravagance in an age where a cup of soba noodles was sold for 1 sen.

The history of Japan’s railroads began with the opening of the Shinbashi to Yokohama route in 1872. At the time, there was an official notice against eating in public, and eating and drinking was prohibited onboard the train. Eating in front of others was seen as poor etiquette, and there was a strong trend of criticizing this behavior. Furthermore, the Shinbashi to Yokohama route only took about an hour then, so it is likely that people simply didn’t need to eat during that time. However, as track sections became longer and journey times grew, it became increasingly necessary to eat while on the train. In those days, trains that operated over certain distances would stop for long periods of time to allow passengers to take care of business at stations along the way. That was where ekiben sellers spotted an opportunity. It is said that from then on, more and more vendors started walking the platforms, and sales of ekiben spread.

With milestones such as the completion of the Tokaido Main Line from Tokyo to Kobe in 1889, the rail network spread across Japan, and alongside it, ekiben sales grew as well.

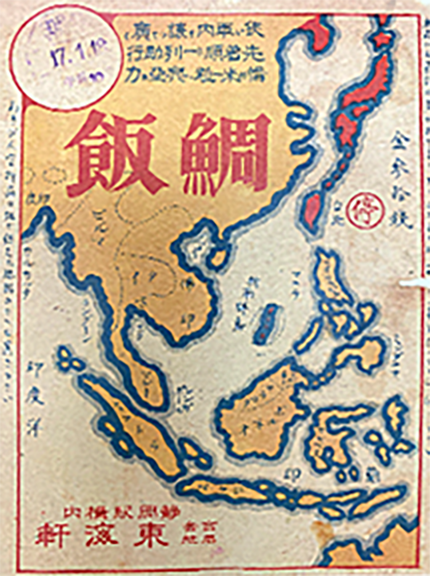

Initially, ekiben was only sold at some stations. However, it seems that the international situation of the time had a major influence on its subsequent wide spread. Until the end of the war in 1945, the military was a major customer of the ekiben industry. The troops within Japan were stationed at key transport positions, and when traveling by rail for drills, mobilization to the front, and so on, ekiben sellers at major stations would arrange bento for the officers and their men (called gunben, or military bento). For example, Utsunomiya was a key transport location, and before the war, the 14th Division of the now-defunct Imperial Japanese Army and others were stationed there. As such, bento sellers concentrated in places like Utsunomiya Station, as well as Oyama Station, Kuroiso Station, Nikko Station, and others. At Utsunomiya Station, there were three major sellers, Shirakiya, Matsunoya, and Fukido, and it seems they provided bento to soldiers coming from Gunma Prefecture, Ibaraki Prefecture, and Nagano Prefecture, as well as from within Tochigi Prefecture, where Utsunomiya is located.

As the war progressed, food and resources were prioritized toward military use, and the food situation became increasingly harsh. Price increases due to rice shortages, travel restrictions, closures of restaurant cars, and so on dealt a heavy blow to ekiben sellers.

in slogans to foster fighting spirit

Summarized Ekiben History

Meiji

(1868–1912)

-

1885 Meiji18Ekiben sales begin at Utsunomiya Station (Shirakiya)

Start of ekiben sales at Yokokawa Station (Oginoya), current longest-standing vendor -

1889 Meiji22Tokaken sells Ekiben No. 1 on the Tokaido Line

Start of makunouchi-style ekiben sales at Himeji Station (Maneki Shokuhin KK)

Start of ekiben sales at Maibara Station (Izutsuya)

Tea sold at Shizuoka Station, Kisha Dobin No. 1 goes on sale (Sanseiken, present-day Tokaiken) - 1890 Meiji23Start of ekiben sales at Osaka Station (Suiryoken), and at Kusatsu Station (Nanyoken)

- 1891 Meiji24Start of ekiben sales (Haginoya) at Baba Station (present-day Zeze Station)

- 1897 Meiji30Start of sales of “Tai Meshi” (bream and rice) at Shizuoka Station (Tokaiken)

- 1899 Meiji32Start of sales of sandwiches at Ofuna Station (Ofunaken)

- 1905 Meiji38Start of ekiben sales at Namaze Station (Awajiya)

- 1906 Meiji39Start of ekiben sales at Kyoto Station (Haginoya)

- 1909 Meiji42Start of “Unadon” (eel fillet on rice) sales (Haginoya)

Taisho

(1912–1926)

- 1914 Taisho3Start of sales of “Tori Meshi” (chicken and rice) at Ban’etsu West Line Hideya Station (Choyokan)

- 1921 Taisho10The Ministry of Railways issues a notice to replace earthenware tea containers at stations with glass containers (cancelled the following year)

Showa

(1926–1989)

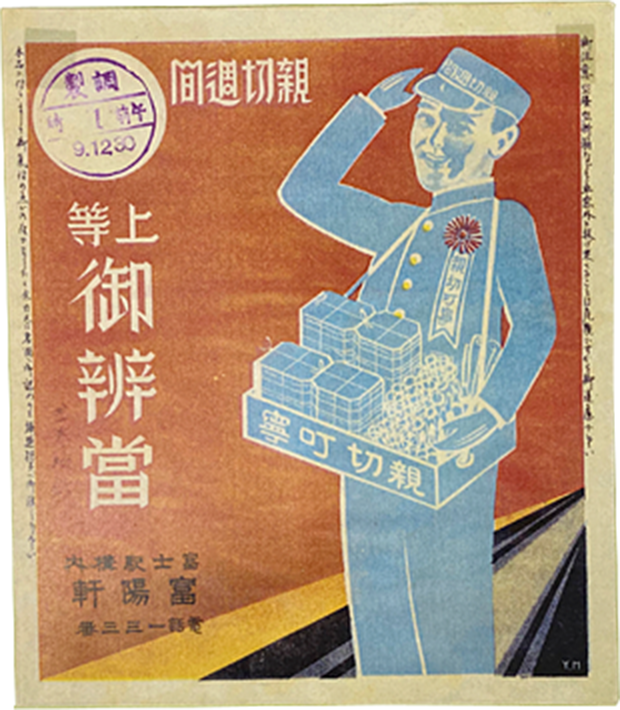

- 1927 Showa2Ekiben vendor outfits change from Japanese short coats to suits

- 1940 Showa15Labels issued celebrating 2,600 years since the start of the first imperial era (nationwide)

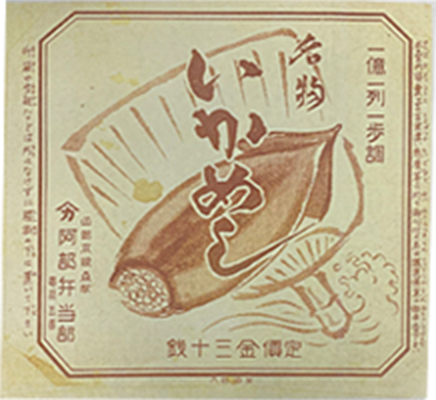

- 1941 Showa16Start of sales of “Ika Meshi” (squid and rice) at Mori Station (Abe Shoten)

- 1944 Showa19Starts of sales of “Gomoku Bento” (rice assortment) and “Tetsudo Pan” (railway bread)

- 1946 Showa21Japanese National Railways Central Committee of Concessionaries formed

- 1953 Showa28Japan first ekiben tournament held (Takashimaya, Osaka)

- 1954 Showa29Start of sales of “Shiumai Bento” (siu mai bento) (Kiyoken, Yokohama)

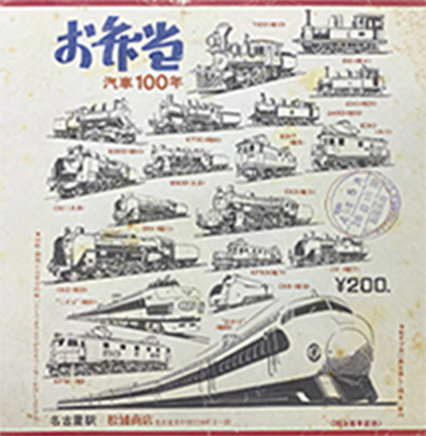

- 1968 Showa43Labels issued for “Meiji Centenary, 100 Years of Steam Engines Series” (Matsuura Shoten)

- 1972 Showa47Start of sales of “Shabu-shabu Bento ‘Matsukaze’” at Kobe Station and others (Awajiya)

- 1985 Showa60Start of sales of TV series tie-in bento “Genki Kai” at Kobuchizawa Station (Marumasa)

- 1987 Showa62Start of sales of “Shinkansen Gurume” (Shinkansen Gourmet) at each station of the Tokaido Shinkansen line

-

1988 Showa63Start of sales of “Acchicchi Sukiyaki Bento” (piping hot sukiyaki bento), a bento designed for heating (Awajiya)

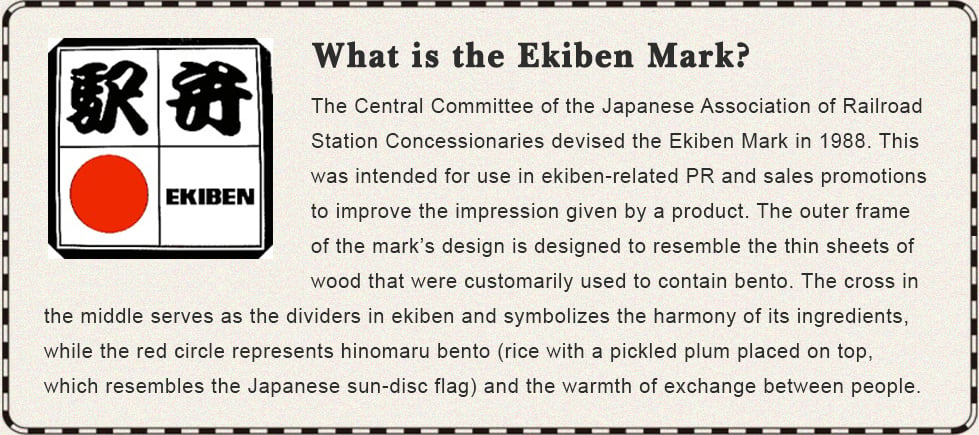

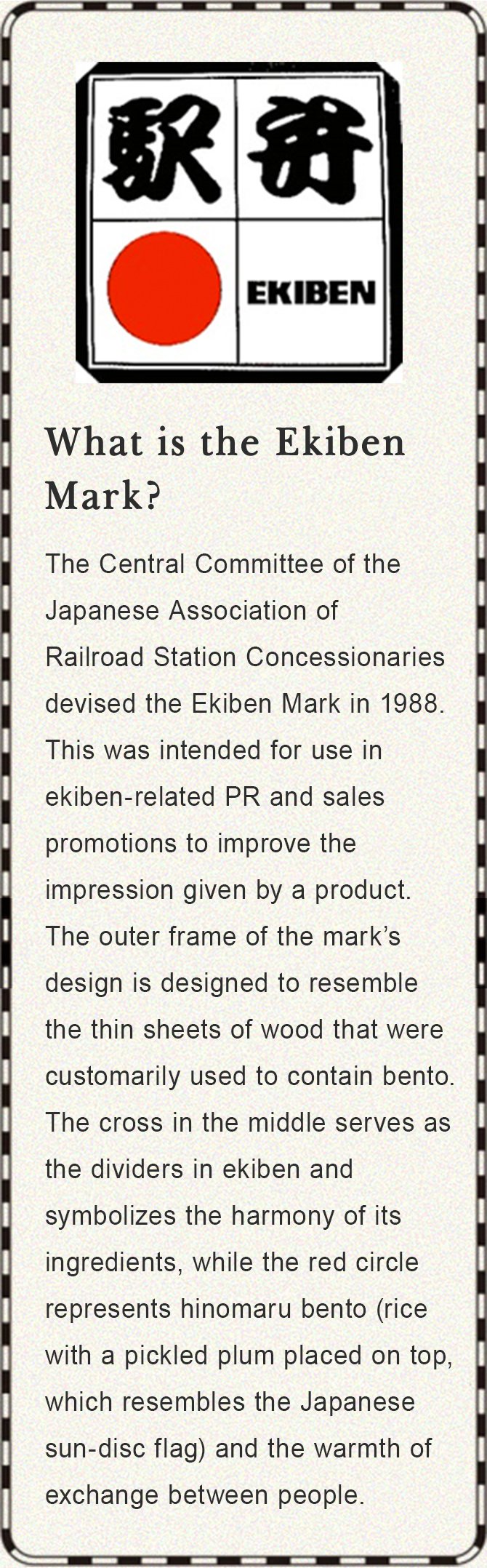

Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries registers the Ekiben Mark as trademark

for Abe Shoten

“Ika Meshi” (1941)

for Kiyoken “Shiumai Bento”

celebrating steam locomotive services (1980)

“Meiji Centenary,

100 Years of Steam Engines

Series Bento” (1968)

Heisei

(1989–2019)

- 1993 Heisei5Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries establishes April 10 as Ekiben Day

- 2016 Heisei2870th anniversary of the foundation of the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries

Reiwa

(2019–)

- 2020 Reiwa2135th anniversary of the birth of ekiben

Material provide by the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries

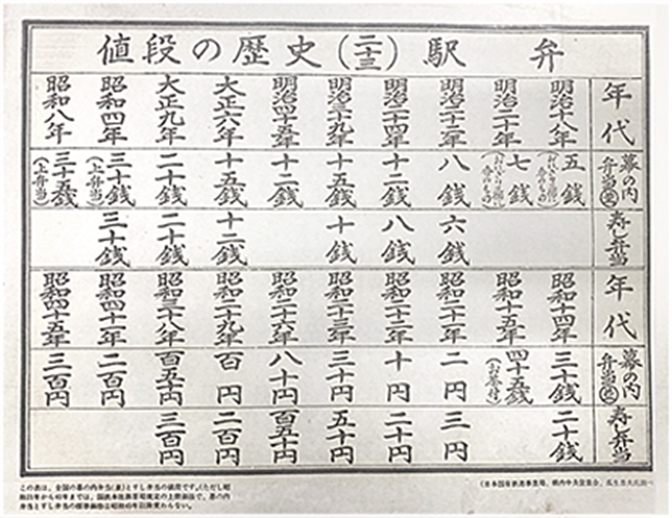

This Table is about the price of makunouchi bento and sushi bento.(Researched around 1970)

(Reference prices of the time)

- 18871 bowl of soba: 1 sen

- 19201 bowl of soba: 8–10 sen

- 19211 cup of coffee: 10 sen

- 19341 bowl of soba: 10sen; 1 cup of coffee: 15sen

- 19491 bowl of soba: 15yen

- 19501 cup of coffee: 30 yen

- 19701 bowl of soba: 100 yen; 1 cup of coffee: 120 yen

Material provide by the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries

With the end of the war came the end of gunben, and through the period of post-war hardship, ekiben arrived at a new stage.

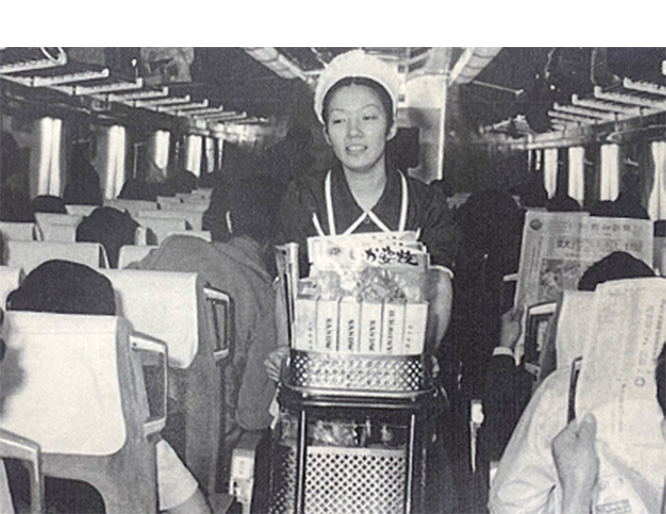

From the mid-1950s, Japan entered a period of high economic growth, and people’s lifestyles became easier, bringing an unprecedented boom in travel. In 1956, the Tokaido Main Line became fully electrified, and in 1964, the Tokaido Shinkansen was opened, giving the boom a great deal of support. During this period, ekiben also underwent a major evolution, with many ekiben using particularly local ingredient from each locale, starting a golden age.

Sold from 1954

Yokohama Station Kanagawa Prefect

Photograph supplied by: Kiyoken Co., Ltd.

Sold from 1958

Yokokawa Station Gunma Prefecture

Photograph supplied by: Oginoya Co., Ltd.

Tokaido Shinkansen Dining car

Photograph supplied by:

Nippon Restaurant Enterprise Co., Ltd.

Mori Station Hokkaido

Photograph supplied by: Ikameshi Abe Shoten KK

During this period, old department stores in major cities like Tokyo and Osaka started to hold ekiben tournaments. Of these, the most famous is probably the “The Original Famous Ekiben and Nationwide Delicacies Tournament” held at a department store in Shinjuku, Tokyo, which had its 55th tournament in 2020. This event takes for a period of about two weeks place every January, with entries of over 300 different types of ekiben, and sales of over 600 million yen! The tournament has been firmly cemented as the biggest ekiben event. There must be a lot of people who want to get a small sense of travel by eating local varieties of ekiben, or perhaps to get a reminder of their home towns. Perhaps the charm of ekiben tournaments is in getting to experience this extraordinary atmosphere.

In 1993, the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries established Ekiben Day. April 10 was chosen for some elaborate Japanese wordplay. The word “bento” is written 弁当 in kanji (Chinese characters), and 弁 resembles 4 (which stands for April, as months are named numerically in Japanese) combined with the kanji 十, meaning 10. Meanwhile, 当 is pronounced in the same way as a Japanese word for “10.” This year, 2020, will be the 135th anniversary of the birth of ekiben.

In 1889, Japan’s first makunouchi ekiben went on sale at Himeji Station. This featured white rice, fish, kamaboko fish cake, and rolled omelet, nicknamed “the three sacred treasures” after the legendary imperial regalia of Japan. This was a luxurious bento that also included accompaniments like simmered items and pickles. Because the original bento was eaten during intermissions of kabuki performances and the like during the Edo period, it acquired the name “makunouchi bento”, meaning “between-acts bento.” This naming was passed on to the ekiben version, and since then, it has become a regular bento choice that can be enjoyed with all kinds of accompaniments.

Photograph supplied by: Maneki Shokuhin KK

The ekiben industry has a long history, and while ekiben enterprises can be prominent businesses even in regional areas, there are also cases of businesses that have been forced to close down in recent years due to factors such as aging proprietors and a lack of people available to take on the business. Additionally, it seems that the uptake of convenience store bento and other such factors means that no small number of ekiben enterprises are struggling.

Ekiben has changed with the times. In recent years, it has become more diverse, with examples such as ekiben using seasonal ingredients and regional specialties, ekiben with elaborate containers that incentivize buyers to keep them, and ekiben collaboration products based on popular anime. Furthermore, the industry is actively working to start overseas branches (in places like Paris, Milan, Taiwan, and so on) and communicate information. In the future, perhaps ekiben will continue to please us by adopting global trends and novel technologies, using these to evolve further.

UWAYAMA_AKIRA / amanaimages PLUS

All uncredited photographs were supplied by the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station Concessionaries.

Born in Shizuoka in 1947. After working at Japanese National Railways and JR East Japan, from 2009 he started working for the Central Committee of the Japanese Association of Railroad Station

Concessionaries. Currently, he is serving as its director-general. Numamoto has a profound knowledge of ekiben, and frequently contributes to magazines, newspapers, and online media.