In the days when there were few places to eat out,

if people had to be away from their homes for long hours or when they were

traveling,

portable meals were common. In Japan, special containers were developed

to

make these portable meals easier to carry.

The foods were prepared in various ways and arranged in a way that

considered

the colors of the ingredients, with the added touches of seasonal

elements.

This evolved into a unique Japanese food culture, which is now so popular

that

the word “Bento” has become a well-known proper name overseas.

Here, we present Japan’s bento culture in various eras and scenes,

together with the characters that appear in those scenes.

As peace descended on the nation and better roads were built, travel became a more comfortable experience, bringing a travel boom to Japan from the middle of the Edo Period onward. When the Dutch physician, Engelbert Kaempfer, visited Japan in the Genroku era (1688-1704), he mentioned the Japanese people’s love for travel in his travel journals, writing that the Tokaido Road was filled with unbelievable crowds of people every day and that, ‘unlike other peoples, the Japanese take many trips.’

It is believed that, around the mid-Edo Period (c.1700 - c.1750), more than three million people a year were traveling the Tokaido Road. At a time when the whole population was around 30 million, this means that approximately one in ten people was traveling.

In the Edo Period, the goods trade and distribution economy flourished, primarily in the cities. This meant that commoners had more money to spare and they had more opportunities to enjoy traveling. In the late Edo Period (c.1750 -c.1850), even farmers were earning more income from cash crops and side jobs during the off-season, so were financially more comfortable.

In the feudal society of those days, officially, common folk were not able to travel freely. However, if they were visiting a place of worship, such as a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple, they were permitted to pass through the checkpoints. Because of this, people from many different parts of the country were interacting with each other on the roads.

However, it was financially unrealistic for common people to embark on journeys that could last many weeks. This is where an organizations called “Ko” came into the picture. These organizations would save up money in a pool and choose one representative to take it in turns to embark on a journey of worship. There were many such ko, such as Ise-ko, Fuji-ko, and Kumano-ko, depending on the object of their worship. These organizations were a kind of “proxy pilgrimage,” offering the same divine favors to all members, even if they did not personally make the journey.

[Crossing Miyagawa River to Visit Ise Shrine] (Jingu Museum)

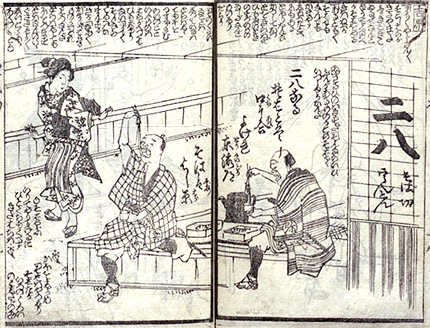

This bestselling novel from the late Edo Period tells the tale of the adventures of two Edo townspeople, Yajiro and Kitahachi, on a pilgrimage to Ise Grand Shrine. After visiting Ise Shrine, the two travelers continued onto Nara, Kyoto, and Osaka. In a second book, they traveled even further and made pilgrimages to Konpira temple in Sanuki Province and Miyajima in Aki Province. They took the Nakasendo Road home to Edo, visiting Zenkoji Temple along the way. This book is evidence of the mood among the people of the time, namely that the Ise Pilgrimage had expanded the range of their travels and that such journeys were becoming more like pleasure jaunts.

(National Diet Library collection)

Utagawa Hiroshige,

Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road

(National Diet Library collection)

-

The Tokaido Road extended a total distance of more than 126-ri and

18-cho (approximately 493 km) from Nihonbashi Bridge in Edo

to Sanjo-Ohashi Bridge in Kyoto.

It took an average adult 12-14 days to travel on foot (35-41 km a day). -

The shukuba, or post station town with the largest population was Otsu, and the post with the most inns, known as hatago, was Miya.

* From the Tokaido Shukuson Taigaicho

[Register of Tokaido Post Station Villages], 1843 -

Onshi or Oshi, a kind of travel agent, would travel around the various parts of Japan, drumming up business for pilgrimages to temples and shrines, and forming ko organizations. They acted in a very similar way to modern travel agencies, assisting travelers to obtain accommodation and providing other services.

*Only those agents seeking pilgrims to Ise were called “Onshi.”

For other destinations, they were called “Oshi.”

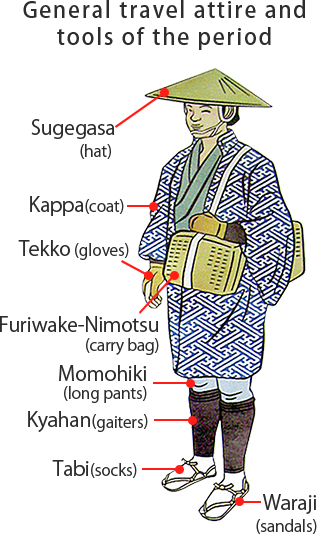

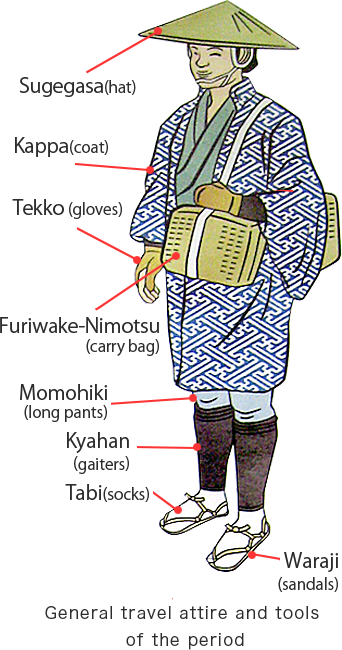

Because journeys in those days were basically made on foot, travelers’ luggage had to be as small as possible and they were careful to carry few items.

This section presents some of the various travel tools that people carried in those times.

![“Besides what is in your pockets, you should carry as few belongings on your journey as possible.” * Ryoko Yojinshu [Travel Advice], 1810](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/text-column01-02-pc.png)

![“Besides what is in your pockets, you should carry as few belongings on your journey as possible.” * Ryoko Yojinshu [Travel Advice], 1810](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/text-column01-02-sp.png)

(Tokaido Kawasaki Shuku Koryukan collection)

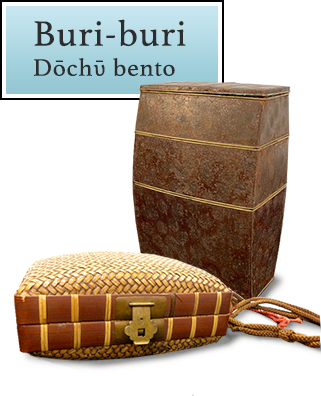

Also known as Hakobento (boxed bento). The three-tiered container is made of lacquered tin plate. The shape, which balloons out in the middle, was known as a buri-buri shape. The basket is made of bamboo woven with a weaving method called ajiro-ami, with a wide strip of bamboo wrapped around the edges and a metal fastener attached. A kind of hook called a sagewa was also attached to allow the box to be suspended from the shoulder for carrying.

(Noboru Seto collection. Cooking supervisor: Hiroko Okubo)

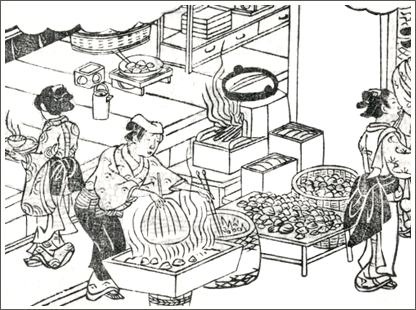

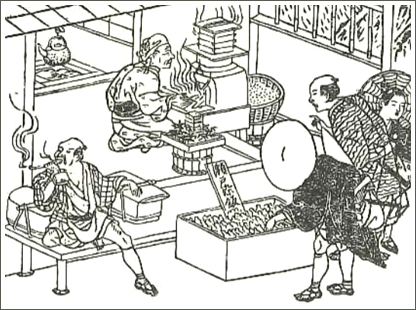

Travelers would eat breakfast at the hatago inn. For lunch, it is believed that they either ate at chaya, or tea houses, along the way, or had the inn prepare onigiri rice balls and other foods and pack them into a bento box they had brought with them.

or meshigori were much valued as

travel lunchboxes from ancient times.

Photograph: Takumi Kogei

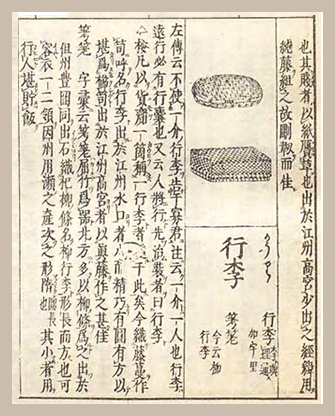

[Illustrated Sino-Japanese Encyclopedia]

(National Diet Library collection)

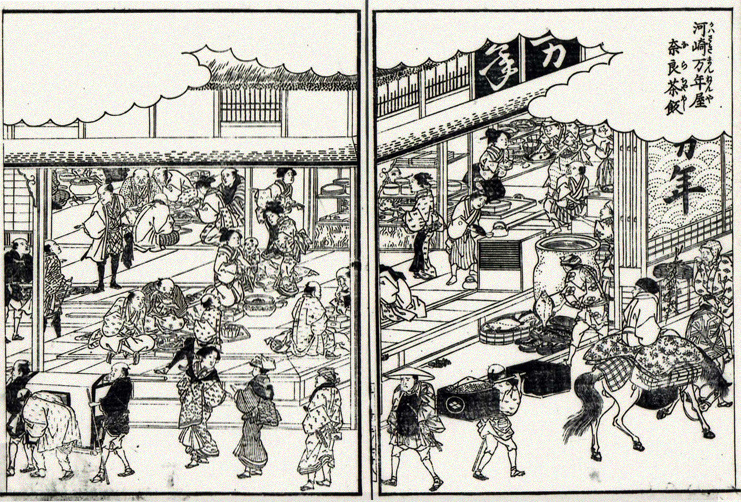

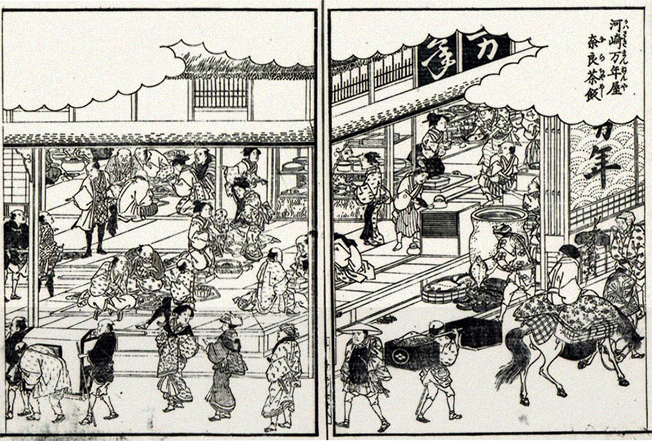

Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Saiken Zue “Fujisawa”

(partial) (National Diet Library collection)

It is believed that commoners went from eating two meals a day to three from around the mid-17th century. The basic form of each meal was one soup and one side dish. Meals while traveling consisted of one soup and two side dishes and were occasionally accompanied by sake. They were quite festive meals, equivalent to what people would eat at seasonal festivals and matsuri festivals.

(Photograph: Tohteru Confectionery)

Nara Chameshi is believed to the origin of today’s teishoku or set menu. The “set” included chameshi (rice steamed with tea, a dish that has origins in Shojin Ryori (Buddhist cuisine) in Nara), tofu soup, and vegetable dishes that had been simmered in soy sauce. The story goes that this meal became popular when, after the Great Fire of Meireki (1657), a tea shop opened at the Kinryu Sanmon gate in Edo’s Asakusa district, and sold this chameshi under the name of Nara-cha. In Saikaku Okimiyage, published in 1693, Ihara Saikaku, a man of letters from the Kyoto-Osaka region, described Nara Chameshi with the words, “There is no more convenient food in the land.” The fictional travelers from Edo, Yajiro and Kitahachi, also ate chameshi.

(Photograph: Tohteru Confectionery)

(National Diet Library collection)

From Haifu Yanagidaru, a collection of Senryu poems of the period.

From Haifu Yanagidaru, a collection of Senryu poems of the period.

Both today and back in those days,

“food” has always been the most enjoyable part of travel.

Travelers felt that they had to eat anyway while on their travels,

so they would try locally-harvested ingredients or rare dishes

from their destinations,

which would give them interesting tales to take back home.

(National Diet Library collection)

One of the most famous dishes on the Tokaido Road,

this soup has apparently been made with a miso base since those times.

Yajiro and Kitahachi ordered this dish at the Mariko post station,

but gave up when the husband and wife who ran the tea house started quarrelling.

(National Diet Library collection)

Chojiya was founded in 1596 and is still in business today.

Kuwana’s clams were famous throughout the whole of Japan from the Edo period. They were even presented to the Tokugawa Shogunate dynasty as tribute. Raised on the rich nutrients that flowed into the bay from the three Kiso rivers, Ibi, Naraga, and Kiso, these clams were known for their plump flesh and rich flavor.

[Tomida Obuke’s Grilled Clams]”

(partial) (National Diet Library collection)

Shincho Koki (Chronicles of Nobunaga) records that this dish was served at a drinking party held on the banks of the Seto River in 1582. It as a portable dish of sticky rice that had been dyed with kuchinashi (gardenia), steamed and mashed before being pressed into small oval cases and dried in the sun.

“Seto no Someii”

(partial) (National Diet Library collection)

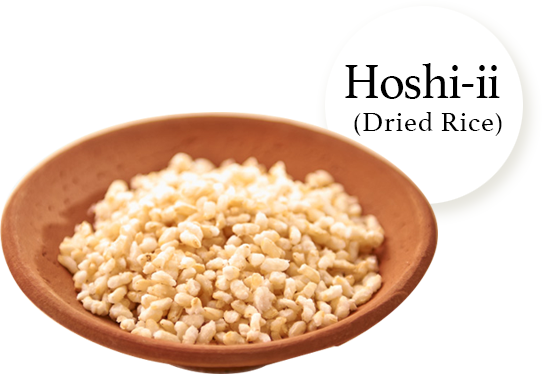

This is a portable meal that goes back to ancient times. It is also sometimes written as kare-ii. Steamed rice that had been rinsed and dried in the sun was placed into bags for carrying. The dried rice would then constituted with cold or hot water before eating. This food has a very long history and appears in a variety of ancient texts and literature.

This text contains a reference to the messengers of Emperor Ingyō keeping hoshi-ii in their pockets in the 5th century.

Now that I journey, grass for pillow, They serve rice on the shii leaves, Rice they would put in a bowl, Were I at home!

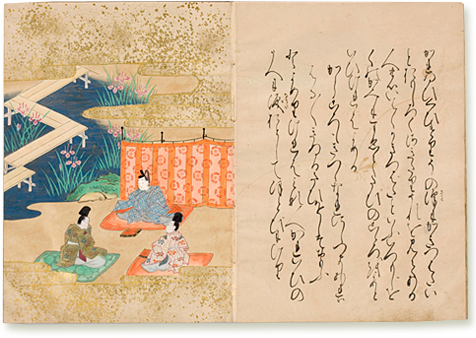

This describes a scene in which Ariwara no Narihira and his companions, on a journey to the eastern provinces, sit down to eat on the bank of a stream in Mikawa Province, where Japanese iris flowers are blooming. Crying with loneliness at departing Kyoto for the east, their tears fall onto their kara-ii (dried rice).

(Center for Open Data in the Humanities)

This ledger for Niekawa-juku, a post station on the Kiso Kaido Trail, contains a reference advising caution to avoid over-soaking the hoshi-ii. In that period, post stations would have cheap lodgings (known as kichin-yado in the Edo Period), in which travelers wanting to save money on their journey would carry hoshi-ii with them and, when they reached the inn, they would pay for the firewood to boil water to prepare their meal, eat their rice, and go to sleep.

Born in Gunma Prefecture in 1943, Hiroko Okubo is the Chair of the Food Culture Division, Japan Society of Home Economics, and a Director of the Washoku Association of Japan. A graduate of the Faculty of Home Economics , Jissen Women's University, she holds a doctorate in Food and Nutrition. Her fields of specialization are Cooking Studies and Food Culture Theory.

![Nihon Shoki [Chronicles of Japan], 720 AD](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-17-pc.png)

![Nihon Shoki [Chronicles of Japan], 720 AD](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-17-sp.png)

![Ise Monogatari [The Tales of Ise] (10th century)](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-19-pc.png)

![Ise Monogatari [The Tales of Ise] (10th century)](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-19-sp.png)

![Kiso Kaido Niekawa-juku no Yadocho [Post Station Ledger of Niekawa-juku on the Kiso Kaido Trail] (1598)](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-20-pc.png)

![Kiso Kaido Niekawa-juku no Yadocho [Post Station Ledger of Niekawa-juku on the Kiso Kaido Trail] (1598)](../../img/bento_library/column/column01/ttl-column01-20-sp.png)